COVID-19, AOTEAROA AND GLOBALISATION

- Greg Waite

Where to start and what to cover, on such a contentious topic? The main facts are clear, and some policies will change next time with the benefit of hindsight - so I'll leave the tricky stuff about cost-benefit analysis, globalisation and alt-Right rebellions until I've laid out some key facts.

Comparing National Management Of Covid-19

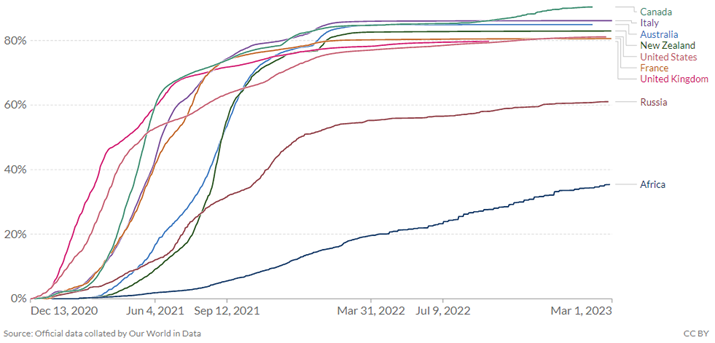

First up, the chart below shows that the populations in large wealthy nations with similar traditions and Government institutions achieved similarly high levels of vaccination, despite big differences in their policy pathways and the clarity of their political messaging. Note that Australia and Aotearoa had to wait longer than Europe and the United States to start vaccination. And poorer nations, illustrated by Russia and Africa, had much lower access to vaccines.

Share Of Population Who Received At Least One Dose Of Covid-19 Vaccine, Cumulative Over Time

All charts from Our World in Data

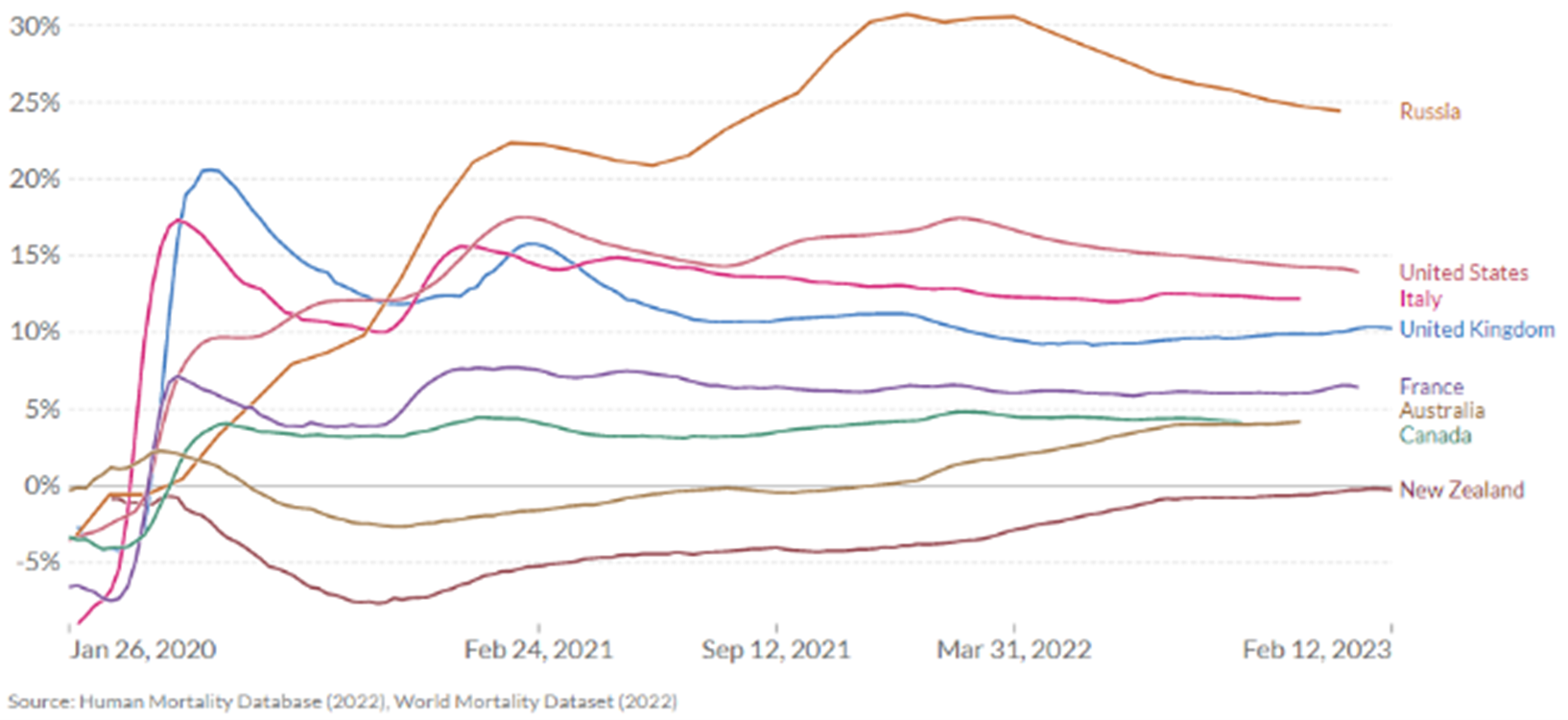

But when we look at the end result of these different policy pathways in the second chart, below, we see there are large differences in loss of life in countries with similar vaccination rates. The best way to measure covid health outcomes across all countries - including those where reporting is unreliable - is to measure "excess deaths" which is the increase in deaths above the normal annual trend. This is because deaths data is harder to fake than health data. Here we can see the results of an inferior vaccine and lower distribution in Russia, but also the effect of poor leadership and/or under-funded healthcare in very wealthy countries like the UK and the US.

Aotearoa stands out as one of a very few countries with cumulative deaths still below our long run average. This means that even with the problems created by deferring other health services during the pandemic, we have saved more lives than normal (e.g., from influenza). Of course, this wasn't all due to policies and clear messaging; Aotearoa had the advantage of its remoteness. With few cases in the country when covid-19 became public knowledge, suppression or near-elimination was still a viable option.

"Excess Mortality": Increase In Cumulative Deaths From All Causes Compared To Projection Based On Previous Years

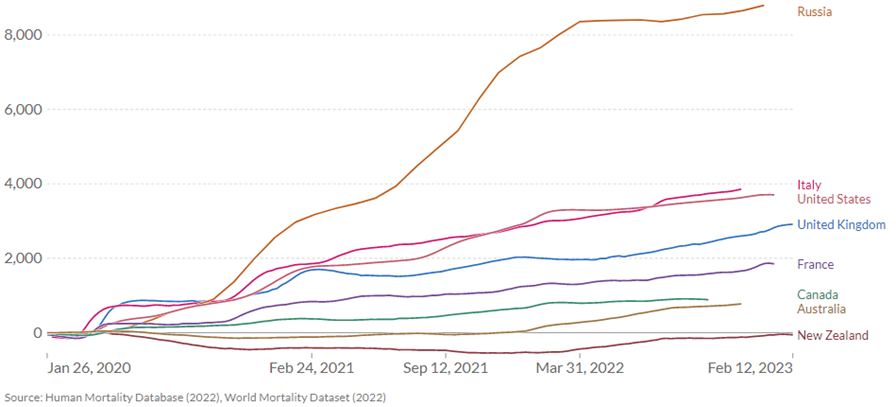

To put numbers on those percentages above, see the third chart below - that's 8,800 extra deaths per million in Russia during the course of covid - one in every 113 people died who would have otherwise lived. For the US it's one in every 270. For Aotearoa, we have still saved more lives than we'd lose in a typical year.

"Excess Mortality": Cumulative Number Of Deaths Per Million Population Compared To Projection From Previous Years

Lastly, here's the latest facts from the excellent Radio New Zealand covid statistics page: Weekly deaths from covid are hovering around ten per week, well below the third peak in December 2022-January 2023 with over 40 deaths per week. We still have 16% of our population without a first dose of the vaccine, 46% didn't get the first booster and 85% didn't get the second. Case rates (per 100,000 population) are notably higher in the Wairarapa, middling in Auckland, lowest in Northland. Around 40% of recent cases are reinfections. The numbers of active cases are high across all age groups from ten to 80, because younger people are less cautious, but hospitalisations are dominated by over-70s.

Remember that when covid was first analysed, experts feared deaths could be much higher. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that there were many more asymptomatic cases undetected. That meant we under-estimated the total case count, so the rate of deaths per case appeared to be much higher. In that context, Aotearoa's early decision to use hard lockdowns and go for elimination was the right choice based on the information we had at the time. Imagine a version of the past where covid was more deadly but we didn't get the early access to vaccines which Europe and the United States had as vaccine developers. It might have been Aotearoa with morgues in the street, not New York.

As it turned out, the long spell with very few cases in our community gave us time to organise contracts for vaccines, then get our vaccination rate up, while also learning from hard-earned experience overseas how best to manage covid hospitalisations and minimise deaths. These advantages were reinforced by our unusually clear political leadership and public health messaging.

Future Pandemic Policies?

Now we come to the tricky question of what we have learnt, and what might we do differently next time. I've heard many experts on the radio and read a couple of books on covid-19 management, most interestingly "The Year The World Went Mad: A Scientific Memoir" by Scottish epidemiologist Mark Woolhouse. Now I understand better how difficult it is to be the expert in a new medical crisis. Every time will be different. Every time requires hard decisions to be made quickly with too little evidence - or put another way, mistakes are inevitable, then we learn from them.

Mark makes this very clear as he traces the evolution of covid modelling, an essential tool to know when we need to use more restrictive policy options. Experts had to learn through watching the virus spread so they could better understand the process and incorporate it in their models - for example, the level and nature of community non-compliance. This is a thankless but necessary stage in getting the models right, and therefore getting the policy mix right.

At the same time, we saw the rise of self-proclaimed experts, advocating for policies which suited their business, political or personal interests. Not coincidentally, this happened in a time when globalisation has first, deliberately fostered an ideology that the State should be downsized; and second, allowed global social media giants to enable national manipulation which encourages angry belief in misinformation. This is a dangerous cocktail.

Still, we shouldn't be dismissive of the real issues which underpin such vocal opposition to vaccine mandates, just because it was encouraged by misinformation campaigns. These are two separate issues. One is what we can learn from understanding the effectiveness of covid-19 management, both here and overseas. The other is about who is behind misinformation, and why.

First, a starting point which would be obvious if misinformation wasn't so common - vaccines work. There's plenty of evidence on this one (1). The pros and cons of other interventions are more complex. I'll start with the conclusions of the book "The Year The World Went Mad". Mark's main point is that lockdowns should have been a last resort, not a first resort, used only when needed to prevent health system collapse. He argues that since covid was mainly dangerous for the elderly and those with co-morbidities, our policies should have been more focused on protecting the vulnerable.

This is a critical point, but then Mark doesn't lay out anything substantial about how we'd protect the vulnerable. In Aotearoa we could imagine a response model which spent more on primary care and community-led initiatives. But equally, I can imagine a future pandemic where a conservative Government pays lip service to community initiatives, and doesn't provide the funding they need. Getting our healthcare management, funding and service delivery right has a long way to go. On balance though, research studies do support using lockdowns more sparingly to avoid health system collapse (2).

Moving on to the vaccine mandate, this was particularly contentious, and rightly so. The right to work and earn a living is fundamental. I get the impression that next time, vaccination in hospital care will remain essential, but not in schools where pupils weren't vulnerable and online teaching was widely used. Then there's a spectrum of jobs in between where the decision becomes more complex. There are research studies which confirm that vaccine mandates significantly increased vaccine uptake in Europe and therefore reduced the loss of life (3). There is also some interesting research questioning the long-term impact of mandates (4). This is a difficult balance, and a call for real experts.

Cross-border travel restrictions have complex costs and benefits. There is research showing travel restrictions were effective in limiting the pandemic (5), research showing that countries with higher Government effectiveness and globalisation were more cautious in implementing international travel restrictions (6); but I was unable to find research which gave a firm and reliable answer either way. Perhaps the best we can say is travel restrictions have a place at the start of serious pandemics but are likely to be relaxed earlier next time, dependent, of course, on the severity of the virus and the speed of new vaccine development.

The simple use of face masks and hand-washing were found to be highly cost-effective (7). But look around you now - hardly anyone, staff or public, was wearing masks during the recent third spike in Covid cases. "Protect thyself if vulnerable" is the unspoken message. Mandatory masks for essential services were a precautionary approach early on while we learned more about this new virus, but is now retained only in medical services because of ongoing staffing pressures, or used voluntarily by those who feel vulnerable.

And experts remind us that it's not over - future pandemics will arrive. We might wake up tomorrow to find the next virus is more dangerous. Wearing a mask is not a big ask to protect essential services like food and transport, or aged care residents. Masks were contentious mostly because there was so much misinformation on social media. Half-lies and hidden agendas, feeding online addiction and anger - what sort of life is this? Who wants to be having an argument with the over-worked frontline staff at the supermarket or the hospital?

The relative value of other Government-imposed restrictions is complex. An early paper in Science (8) found "Limiting gatherings to fewer than ten people, closing high-exposure businesses, and closing schools and universities were each more effective than stay-at-home orders, which were of modest effect in slowing transmission". A later paper (9) ranked a range of mandates by a Stringency Index, concluding that more restrictive policies were not necessarily more effective than the right range of less restrictive policies. See also the section below which considers both benefits and costs.

Now we come to the really tricky questions. Were the benefits worth the cost? What kinds of costs and benefits do we include in this equation? There is a big literature on covid cost-benefit analysis. If you want to look at just one example you could read Broughel and Kotrous (2021) "The Benefits Of Coronavirus Suppression: A Cost-Benefit Analysis Of The Response To The First Wave Of Covid-19 In The United States" which concludes that State-led suppression policies had net economic benefits (e.g. less business closures due to illness) when compared to a private or voluntary response.

But not all cost-benefit studies are rigorous. Crude examples were published early on which simply compared the death rates under different covid management policies with the economic costs of the policies - lockdowns or not, travel bans or not, stay at home orders, etc. Over time, more realistic analyses have been published which include estimates of health system collapse, mental health impacts, deferred health services, and more. "Meta-analyses" have then combined the best studies and offered more reliable overall conclusions, where possible.

Juneau (2022) concluded "a cautious interpretation suggests that (1) workplace and school closures are effective but costly, and (2) scaling up as early as possible a combination of interventions that includes hand-washing, face masks, ample protective equipment for healthcare workers, and swift contact tracing and case isolation is likely to be the most cost-effective strategy". Vandepitte et al (2021) (10) recommended a stepwise approach where policies shift on the basis of predefined triggers, and a broader long-term view for future cost-benefit studies.

So, there are studies which show net benefits for some interventions, studies which don't, but none which offers a complete picture of costs and benefits. Just one example to illustrate: Today, Aotearoa is still struggling to attract enough staff to keep our health system going due to global staff shortages, high local housing costs and low wages. How do you cost in new policies so our health system is more prepared next time? In the end, we are reliant on expert advice from our health sector and our collective organisational, political and community memory; how well our institutions, our politicians and our public understand what we did right and what we did wrong.

,Globalisation And Covid-19 In Aotearoa

Which brings us to globalisation - higher volumes of trade, capital flows, migration flows and the increased political and social influence of global corporations. Firstly, corporate cost minimisation through global just-in-time supply chains was disrupted by high levels of staff illness in poor and rich countries. This created today's persistent cost increases for food and other globally traded goods. Second, sustained pressures on health staff in wealthy nations created a spike in early retirement, so our reliance on taking the skilled staff from poorer nations also spiked. This is both unjust and unsustainable - we need to return to training our own public services. Undermining poorer nations to reduce rich-nation health costs has to stop.

Third, we need to build worker and housing advocacy organisations. Lots of Kiwis returned to Aotearoa during covid, but most left again. You can train new staff, but you won't keep them if wages are too low and housing costs too high. Improved wages and housing would also help those on the margins of our economy who were drawn to covid misinformation because their lives are so tough - globalisation has taken away many low-skilled jobs, replacing them with service work for the rich which demands smiling subservience ('customer service').

Fourth, we need a many-sided response to the increasingly aggressive and illegal manipulation of public attitudes in social media. The big picture on this is explored more fully in my review in this issue of Maria Ressa's book "How To Stand Up To A Dictator."" Maria explains clearly how corrupt Governments are employing secretive companies like Cambridge Analytica to inflame angry self-righteousness among those most vulnerable to misinformation.

This secretive manipulation is reinforced by the more subtle and mainstream promotion of pro-market ideology. Maria refers to this as a "meta-narrative" - in plain language, the emotional place these strategies want to lead you to. Both encourage you to believe the problem is bad Government, so the solution is less Government. Forget that education, good wages and age pensions, affordable healthcare and housing are the foundation of a better life, and all these depend on Government regulation and spending. Be angry, not thoughtful. Don't pay attention to the rising influence of global and local corporations on Government, don't support reforms like limiting political party funding to public funding.

Go Offline, Try Real Life Instead

What I found surprising and so refreshing in Maria's book was her positivity. Through years of authoritarian harassment and online attacks, both personal and political, she has learned that the only way forward is through deeper understanding and increased collaboration. This looks pretty appealing when contrasted with a life spent online and constantly angry, which is the aim of Facebook's algorithms.

Why not reduce your social media time, starting today? Learn how to live without Facebook, YouTube and Google. Don't pursue a celebrity version of a better life, don't follow online trends and click-bait. Talk to actual people instead of watching endless videos on the Internet. You'll find more to smile about in real life. Don't get angry and self-righteous, but work together with others and expand your horizons.

Finally, we need to give poorer nations more power in multinational forums and we need to build a much more effective civic society, or we will continue to be over-run by policies which transfer wealth to global corporations. This needs real innovation. Again, Maria Ressa's book is a good start for the many new democracy-building ideas trialled at her online news website Rappler, but we are only just beginning to ask these questions and we have a very long way to go.

Endnotes

- Lopez et al, "A Cost-Benefit Analysis Of Covid-19 In Catalonia".

- Allen, DW, "Covid-19 Lockdown Cost/Benefits: A Critical Assessment Of The Literature", International Journal of the Economics of Business, Volume 29, 2022 - Issue 1.

- Karaivanov et al, "Covid-19 Vaccination Mandates And Vaccine Uptake", Nature and Human Behaviour 6, 1615-1624 (2022).

- Bardosh et al, "The Unintended Consequences Of Covid-19 Vaccine Policy: Why Mandates, Passports And Restrictions May Cause More Harm Than Good", British Medical Journal, Volume 7 Issue 5 (2022).

- Eckardt et al, "Covid-19 Across European Regions: The Role Of Border Controls", CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP15178.

- Bickley et al, "How Does Globalisation Affect Covid-19 Responses?" Globalisation And Health 17, Article 57 (2021).

- Juneau et al, "Lessons From Past Pandemics: A Systematic Review Of Evidence-Based, Cost-Effective Interventions To Suppress Covid-19", Systematic Reviews 11, Article 90 (2022).

- Brauner et al, "Inferring The Effectiveness Of Government Interventions Against Covid-19", Science Volume 371, Number 6531.

- Spiliopoulos, L, "On The Effectiveness Of Covid-19 Restrictions And Lockdowns: Everything In Moderation", BMC Public Health 22, Article 1842.

- Vandepitte et al, "Cost-Effectiveness Of Covid-19 Policy Measures: A Systemic Review", Value Health 2021 Nov. 24(11).

Non-Members:It takes a lot

of work to compile and write the material presented on these pages - if

you value the information, please send a donation to the address below to

help us continue the work.

Foreign Control Watchdog, P O Box 2258, Christchurch, New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Email