REVIEWS

- Linda Hill

THE LAWS OF CAPITALISM New Economic Thinking "All things can be coded as capital, with the right legal coding" says Katharina Pistor, Professor of Comparative Law at Columbia Law School, in "The Code Of Capital: How The Law Creates Wealth And Inequality" (Princeton, 2019, $NZ38 via Fishpond). She provides a free and easy version in an excellent online lecture series1, which I review here.

Pistor explains how assets such as land, private debt, business organisations or knowledge are transformed into capital through contract law, property rights, collateral law and trust, corporate, and bankruptcy law. She explores the history, processes and institutions through which private actors have generated not only economic inequality but also inequality in law, "enabling them to opt out of jurisdictions, restrict government policies and erode democracy".

For a non-lawyer Leftie like me, her explanations of the role of law in shaping and maintaining otherwise familiar areas of political economy are a fresh perspective - educational and really interesting. Her presentation style is relaxed, her language is professional and unemotive, but clearly her intention is to speak truth about power.

In 2023 political power in Aotearoa showed signs of regulatory capture, on agricultural emissions and Three Waters. Our newly appointed Labour PM rushed up to Auckland to meet with business leaders, policies were dropped and Fonterra received an additional $2 millions' worth of free carbon credits. Industry capture and soft corruption seem even more obvious with the present troika Government.

But, according to political theorist Claus Offe, in an old paper that surfaced in my garage, the liberal democratic Welfare State does not favour specific interests and is not allied with specific classes. Rather it protects and sanctions a set of institutions and social relationships necessary for the domination of the capitalist class. It seeks to implement and guarantee the collective interests of all members of a class society dominated by capital (his italics). A discouraging thought. Whether politicians are captured or not, the game is rigged.

"Institutions... Necessary For The Domination Of Capital"

They are exactly what Pistor talks about. However, both the law as an institution, and specific areas of law, are outcomes that were - and continue to be - socially, economically and politically contested. She begins with "Coding Land And Ideas" into capital assets and property rights. Land, used for food for millennia, becomes "property" once it is encoded in law. Law establishes who decides how land will be used and for whose benefit. She takes illustrations from land enclosure in the UK, indigenous land rights in Belize, and white settler colonisation.

Until 1880, ownership of rural land was the main source of wealth. Laws give advantage to the holders of assets, and rights of enforcement, Pistor says. Over time and through the courts, particular understandings of property rights emerge: it is an individual right, a right to exclude others, a right to sell, a tangible use right and even, most recently, a right to "expected future value". From the late 19th Century legal devices were introduced - private law, contract law, corporate law - that can turn intangible promises of payment, ideas (intellectual "property") and databases into tradable, wealth-generating assets.

Since an idea is inherently shareable, law is used to enclose it, assign property rights and enable monetisation. From trading bank notes to credit default swaps, from copyright to attempts to patent human genes. The new types of rentier assets discussed by Brett Christophers are all what Pistor calls "creatures of the law" (see my review of Christopers' "Rentier Capitalism. Who Owns The Economy And Who Pays For It", in Watchdog 162, April 2023).

In "Coding Debt", Pistor explains the role of law in turning the simple IOU of history into the payment systems, securitised debt assets, tradable derivatives and elaborate financial contracts of today. This includes a quick but very clear explanation of the multi-layered trading in cash flows from house loan interest and repayments that caused the 2008 global financial crash.

Her third lecture on "Lawyers, Firms And Corporate Entities" explains legal history from simple partnership agreements to colonial joint-stock companies in the 1600s with State Charters and legal person status, and the 1800s' statutes that simplified the creation of corporations. By the 1900s the law had enabled the corporation to become the dominant form of business organisation under capitalism.

Pistor tells how Lehman Brothers used corporate law to organise a complex holding company whose shareholders profited while its debt-strapped subsidiaries collapsed like a house of cards. The combination of public law and our public money/reserve bank systems, she says, is one of the most powerful ways that wealth is created today.

Rescuing Banks & Companies From "Market Failure"

So liberal democratic states provide the legal forms that underpin capitalist accumulation, and in cases of "market failure" may step in to rescue private banks or companies - as happened with Northern Rock and Goldman Sachs (though not Lehman) in 2008. In early 2023, three Silicon Valley banks, specialists in IT venture capital, failed and were taken into receivership by California and Federal agencies.2 They liquidated one, sold one, and re-floated the third after asset sales. This was the third largest US bank failure in history, again rescued by Government but this time without using taxpayers' money.

In "The Tool Kit", Pistor explains that law provides four essential tools to protect corporate ownership: priority rights to property, durability of corporate ownership, universal applicability and enforceability of these, and convertibility into cash or other assets. This is done through legal institutions, and particular bodies of law: property, collateral, trust, corporate, bankruptcy and contract law.

These are not static, but evolve and expand, usually driven by interested parties - who seek to change the interpretation or application of a law, or lobby for legislative changes, or by picking and choosing which law applies and which jurisdiction to pursue it in. States centralised and institutionalised the means of coercion, but some of these can be accessed by private litigators in a highly decentralised fashion. This is easier for some than for others, because of differences in "legal standing" to sue, or because of costs. Moreover, many cases are settled, rather than risk contributing to case law that might have wider effects.

Although governments and juridical precedent establish the law, it is private lawyers who find flaws, loopholes or inaccuracies, shaping and moulding the legal code over time. Pistor terms these "The Code Masters". Not all interpretations are tested in court. Most transactions and contracts between parties are private, unless listed companies and financial assets are involved (the Canadian TV drama series Suits illustrates this).

Law-making also occurs in negotiations and lobbying between lawyers and regulators. New legislation may follow legal practices rather than predate it. Pistor recounts the development of the legal profession in England, Prussia and France, then in the US. US lawyers who picked and chose between state legal systems (e.g. Delaware for tax advantages) became adept at this internationally, once rules on international trade and capital flows permitted.

The US law service industry is worth around $US350 billion, with revenue increasing in 2021 by over 14%. Many lawyers do public and community work, but the highest paid work for large national firms is in the business of coding capital. From the 1990s, some went global, often through mergers with local firms. In France and Germany, in areas of law like mergers and acquisitions, or capital market law, half to two-thirds of market share is now held by global law firms. In the UK a "magic circle" of such law firms facilitated transfers of privatised capital out of the former Soviet Union.

UK laws and US laws (particularly Delaware state law) have become the default systems used for transnational commerce, finance and corporations. Capital is now transferred globally with the click of a mouse. Pistor's sixth lecture "A Code For The Globe" will be familiar territory for CAFCA members, but she provides a really useful account of the history and issues involved. People may assume some kind of "free" space outside domestic laws, she says, but in fact a system had to be created through law to underpin global markets, particularly global financial markets.

This allows the entry into countries of goods and, more importantly, of finance for various purposes, with currency conversion and other increasingly standardised rules. For example, the European Union created a "European Passport" that allows holders to do financial business throughout the EU. After Brexit, UK financiers lost this, leading some to move offices to Dublin, Paris, Amsterdam or Frankfurt. Capital is further encoded through international conventions, institutions (World Trade Organisation, International Monetary Fund, World Bank), and trade agreements (including the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights -TRIPS).

There's also the "soft law" of non-binding model codes, such as the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development's on corporate governance which endorses shareholder primacy3, and, until 2021, the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Index. In bilateral and multilateral investment treaties, individual countries may have ceded too much, Pistor says, and she explores the tension between democratic sovereignty and globalisation.

Desirable domestic regulations and protections sought through local democratic processes can be hampered by the threat of expensive lawsuits under free trade agreements. Freedom of capital movement across borders brings local issues under off-shore legal jurisdictions, imposing restrictions on national and local governments, elevating the private rights of capital above the public interest, and eroding democracy.

"Bilateral investment treaties," Pistor says, "are a wonderful example to show how states enable powerful private actors to claim property rights and priority for themselves and use them against the interest, the laws, even the constitution of another state". In "Transforming The Code Of Capital", Pistor reminds us that the legal system is a social resource, so there is an alternative. At present, the system violates principles of fairness in the use of a common resource, the law; it violates concerns about how we distribute wealth and power; and it has violated and eroded our sense of "self-authorship" as democracies - what we'd call self-determination.

Law Serves Capital

The law has been harnessed by private actors to accumulate immense private wealth. This has produced economic inequality, and also inequality before the law. But, she suggests, we can incrementally rewrite the legal code to make it fairer. The burden of change need not always fall on governments - other tools and institutions can be created. Adaptation in a decentralised fashion is not a bad thing, in her view; the question is who does it, for what purposes.

"We haven't solved this issue yet", says Pistor, so she recommends an approach to change that she calls "strategic incrementalism" or "transformation through incremental change". By studying the legal system carefully and making key changes, we can open new policy spaces, redesign the system and create new institutions. This process will provide openings for alternative ways of doing business and alternative ways of organising society.

She proposes that we begin by rolling back some of the legal privileges and exemptions, legal privileges acquired by capital over centuries, setting jurisdictional boundaries that ensure the same rules apply to everyone, and ensuring that those who benefit carry the full social, economic or environmental costs of their actions and no longer push them onto others. On examination, conventions like limited liability, legal certainty and legal enforceability may not always be appropriate, she says. By way of illustration, she notes that speculative agreements ("wagers") became legally enforceable in the US only in 2000, causing financial markets (and bubbles) to take off.

Pistor is currently leading a research project on global finance and the law. This is developing new theory about the relationship between law and finance, using case studies drawn from the global financial crisis as analytical windows for determining deficiencies in established thinking. I look forward to reading about it.

For a science fiction solution, try "New York 2140" (2017) by the wonderful Kim Stanley Robinson. I kid you not - it kicks off with two computer coders in high-frequency trading, camped on top of the MetLife tower in the flooded city, with its dark pools of money. They hack financial capitalism to rewrite its 16 essential codes, and the story continues about changing the system for the good. Robinson also addresses near-future solutions for climate change in "The Minister For The Future" (2020).

Back to Pistor. She says at one point, the law counts only if you can enforce it. It can be hard to enforce the law against governments, because governments control the coercive powers of the State. On the other hand, the State's coercive powers can sometimes be accessed to sue corporations. And here we are in the territory of my next review.

THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE LITIGATED This is a fascinating and very readable collection of first-hand accounts from activists and lawyers at the front line of social movements around the world. The title is a nod to a great 1970s' poem/lyric by Gil Scott-Heron1 about the Black civil rights movement. As Jane Fonda's Foreword puts it: "The law is no magic bullet... but if you understand its' power as a tool, you can harness it".

The legal framework of capitalism that Pistor explains began in the rise to equal power of the European bourgeoisie against the old power of the landed classes, which they achieved through liberal democratic politics based on Enlightenment concepts. The principle of equality in law therefore underpins capitalism's judicial institutions, but certainly not the practice of equal rights for all classes or all social groups, or on all issues.

Nonetheless, the law may provide a fulcrum which lawyers and activists can lever as part of social movements for change. Sometimes the fulcrum - a particular piece of legislation - needs first to be created through politics. Sometimes it requires both litigation and public activism before a provision already in the law is respected and enforced.

Legal work is often about achieving an outcome for just one or a few individuals. These writers are saying that for any litigation to have success in changing society, it needs to arise from, and be backed by, a social movement or a community. Going to court can be a successful strategy for social change if lawyers and activists are working together as part of a rising political force.

"It Takes A Lawyer, An Activist And A Storyteller To Change The World"

That's the maxim that led to this book. Its' stories are about campaigns using the law against military brutality in Burma; for gay rights, sex worker rights and equal AIDS treatment in Kenya and South Africa; discriminatory policing and Black Lives Matter in the US; reproductive rights in Ireland and Poland; ending female genital mutilation in Africa; defending protestors in Lebanon and Russia; fighting for indigenous rights and land rights at Standing Rock, Mexico, the Peruvian Amazon and Ghana. Julian Assange's lawyer talks about defending him and WikiLeaks' campaign to hold governments accountable.

In a section on the climate emergency, young activists tell why they led school strikes in Manhattan and Turin; a veteran anti-apartheid activist talks about community water rights, a corrupt nuclear power deal and climate action; and an angry UN climate negotiator glues herself to Shell's front door. Now more than 140 countries include "Green Rights" to a clean and healthy environment in their constitutions, with Bolivia and Ecuador giving rights to nature itself. In 2019 in the Philippines, a human rights case was taken against 47 carbon-polluting fossil fuel corporations.

Not all nations are liberal-democracies, or have judiciaries independent of their power structure. In some, activists and movement lawyers put their freedom or their very lives on the line. So, in the late 1990s, Burmese activists, with Redford as their lawyer, initiated an international approach. A pipeline to take oil from the Andaman Sea to Thailand was being built with forced labour, torture and deaths at the hands of the Burmese military in the interests of US energy company Unocal. Doe v. Unocal was the first ever case against a global corporation in its home jurisdiction, the USA, for harm caused overseas (under an old but little used Alien Tort statute2).

It was a success that, despite setbacks in a higher court, put global corporations on notice. Another story is about a case to establish whether the International Monetary Fund and World Bank can be held legally accountable in Washington, the legal jurisdiction in which they are headquartered, for harms caused by development projects they funded in India.3 And a Chinese lawyer, now based in Washington, is working to hold China accountable under international law for environmental pollution from its' development projects at home and abroard.

These writers do not suggest that legal action is the best or the only strategy for change. It's one among others that may be appropriate to the time and to the particular cause. The law may guarantee rights (like education or housing) but that doesn't mean it has the ability to deliver them. And the pace of cases through the courts can be glacial. The point of these stories is to provide insights from the differing perspective of activism and the law - sometimes from both about the same case - and to draw out the lessons learned.

A central lesson is that the decision to take a case, and how to progress it, should always be made by those affected, by the grassroots community. Another is, even if a case that fails or is settled for compensation, that may advance the cause politically, or build the movement, or strengthen the community. Having their "day in court" means an opportunity to be seen and heard, to make the powerful sit and listen to the harm caused.

Redford agrees with Audre Lorde that the master's tools may never dismantle the master's house. But maybe the law can be used to temporarily beat him at his own game and, as part of a movement with mass mobilisation, protest and public advocacy, can bring about genuine change. "The law... has the power to be transformational. But the revolution will not be litigated. It will be fought by those with most at stake, with the help of the law in the service of the movement".

Ten Rules For Radical Lawyers4

This collection of experiences in law and activism is a good general read for anyone. I recommend it as a valuable read for activists, and a must-read for any law student or practitioner who aspires to be a "movement lawyer". In the US, young people have been taking - and winning5 - lawsuits against state governments for policies that exacerbate the climate crisis.

In 2023 the European Court of Human Rights heard a climate case taken by six young Portuguese against all 32 European Union member countries.6 Lawyers are taking a stand too. In March 2023, 140 prominent lawyers from the UK and around the world published a Declaration of Consciousness which stated that they will withdraw their legal services from (i) new fossil fuel projects and (ii) criminal or civil action against peaceful climate protesters.7

In Aotearoa, Lawyers for Climate Action has filed two cases so far about our slow pace of climate change policy and our inadequate Emissions Trading Scheme. Former Greens Co-Leader James Shaw's parting gift is a Member's Bill, now progressing through Parliament, to add the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment to the Bill of Rights Act.8 Mike Smith (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) has just received Supreme Court clearance to sue seven big polluters for their role in climate change, and the Waitangi Tribunal has accepted a priority kaupapa Treaty claim into Government climate change policy.9

Endnotes:

LAWFARE VS DEMOCRACY This report is a more dispiriting take on the use of the law. It comes from Progressive International, a "common front" formed in 2018 to "unite, organise, and mobilise progressive forces behind a shared vision of a world transformed". Interesting people, based everywhere. Democracy is under threat, says Progressive International, though it retains its' status as the dominant paradigm for national governance.

Within this, "lawfare" or legal warfare is becoming a dominant tactic. This is the deployment of judicial power to persecute political opponents: candidates, parties, non-Government organisations (NGOs) and social movements. The term was coined by US Air Force Col. Charles Dunlap in 2001 to describe "the use of the law as a weapon of war", potentially at an international level against the US and its allies. Latin America has been the laboratory for its use, but it's now going global.

Latin American Case Studies

This short readable report discusses the tactic's origins, application and implications, and provides three case studies - from Brazil, Ecuador and Guatemala - where it has already irrevocably changed political history. After the end of the Cold War, Latin American was experiencing a "pink tide" of democratic rejuvenation, which began to unify regionally. To push back, Rightwing forces turned to the judiciary.

Lawfare comprises several generalisable components, say the authors. It depoliticises issues by turning political questions to technocratic ones, to be decided by bureaucrats, lawyers and judges. Ownership, redistribution, power and social justice are turned into legal questions about wrongdoing, procedural error or proving accusations. Lawfare obfuscates the political and economic interests involved. This is then leveraged through concentrated privately-owned media power to "manufacture consent". There is no popular basis for lawfare, almost by definition - it operates "from above".

A Strategy Systematically Mobilised Against Popular Forces

Its' objectives are flexible, with low political costs - even if a larger goal is not achieved, key organisers or political opponents may be eliminated at a crucial time. But it is just one part of a broader toolkit, ranging from media propaganda to economic weapons to military action, and everything in between. If we are to combat lawfare, says Progressive International, we must understand it not as a catch-all but as a strategy systematically mobilised against popular forces.

The detailed case studies are of lawfare against:

Lawfare is not exclusively a Latin American phenomenon. Progressive International says it was being deployed in 2023 in Turkey to ban the People's Democratic Party just days before the general election, and in India where Prime Minister Modi used a judicial pretext to raid opposition party headquarters and remove leading figures from Parliament.

The structure of lawfare cannot be dismantled by elections alone, as it hinges on the behaviour of unelected judges, journalists and editors. It may even be driven from abroad. International solidarity campaigns can offer critical political and financial support, together with legal aid or investigative journalism. This can play a crucial role in resistance.

REVIEWS

- Greg Waite RIGGED Nearly all economists work for vested interests, so their skills and knowledge are rarely used to explain the real workings of our economies. Baker is one of those rare exceptions. I discovered his 2016 book in Whangarei Library, and review it here despite its age because it promotes a new approach to reforming capitalism. It was very refreshing to see plain language and mainstream economics used to make the case against the current crop of "orthodox" economic policies.

Finding this book reminded me of when I read Stiglitz's "Globalisation And Its Discontents"*. After years of global "development" and "lending" institutions undermining developing nations with economists' blessing, finally a disaffected insider confirmed what readers of Watchdog had known all along - they were acting in the interests of Western share markets and financial institutions. *Reviewed by Jeremy Agar in Watchdog 105, April 2004, Ed.

Baker's focus is again on globalisation and, in a link to Stiglitz, the book's introduction reminds readers that orthodox trade economics suggests surplus investment should flow from richer nations which have a surplus getting lower returns, into capital-poor developing nations, gaining higher returns and assisting their economic progress. And this is what did happen in the developing world through the 1990s, when countries like Indonesia and Malaysia experienced rapid annual growth of 7.8% and 9.6% while running large trade deficits.

Those deficits kept rising until the capital inflows from developing countries reversed. Fixed exchange rates were abandoned and the International Monetary Fund prioritised debt repayment, replacing the era of deficits and growth with surpluses and austerity. On Baker's calculations, the countries of East Asia would be far richer today if orthodox economic policies had continued - South Korea's per capita income would now be higher than the United States. Unfortunately, the US-led West had found new ways to make more; shifting their own production offshore, selling derivatives, financialising production, monetising their Internet monopoly, etc.

Addresses The Myth Of The Free Market Head On

Markets are never free. Property relations are defined, contracts are enforced, macroeconomic policy is implemented - all markets are determined by policy choices. Baker puts it bluntly - it's not the "invisible hand" guiding changes in the market, it's the hands of the financial and political elites at work to ensure the market works in their favour. He keeps it simple, sticking to explanations of just five mainstream economic policies which shape today's economy to distribute income upwards, then offering new responses which are plausible and egalitarian:

The first of these is the most important issue raised in Baker's book. In favour of full employment, he points out that reshaping the way incomes and profits are distributed by changing the way the market works is more effective (harder to avoid) and efficient (costs less) than our current approach of partially reallocating afterwards through Government taxes and transfers. This point applies to most of his solutions - change the core way the market functions, don't just play round the edges.

Baker emphasises that unemployment is a deliberate policy choice. A full employment economy is clearly beneficial to workers and "the key element in assuring the benefits of growth are shared equally throughout the income distribution". In a full employment economy, workers have more bargaining power to ensure they get a fairer share of the gains from growth. In support, he points to the much higher rates of unemployment for Black Americans. The usual solutions, tweaks to tax and transfer policies, will never be as effective as providing those unemployed with an actual job and a future.

"Change The Market"

His "change the market" approach is very relevant for NZ, where the split between Right and Centre parties means that gains in social support payments are regularly rolled back under successive conservative Governments. The current Coalition has already lowered the minimum wage and benefits (I assume that no Watchdog readers are fooled by the usual announcements of dollar increases which are less than inflation; the only increase which counts is a real increase, after allowing for inflation).

And behind those headline benefits lie many secondary payments which are never increased by National when it's in Government, adding to the total cuts. On top of reducing benefits, the Coalition is reinstating punitive sanctions on our poorest families - cut their income rates, then cut them again as punishment. This gives them the "sell" for their policies - "beneficiaries choose unemployment" - the exact opposite of the truth. Today's neoliberal governments deliberately create unemployment by prioritising inflation over full employment. A wide range of policies are shaped by that decision to prioritise inflation over employment:

The financial industry and some powerful business interests oppose full employment as they lose their excessive share of income. For the bank and finance industries, inflation reduces profits from lending; for business, increased bargaining power for workers means more money paid out in wages. Another of Baker's big points is that the public is often confused when big numbers are cited for welfare payments, falling for the conservative line that they're excessive and unaffordable.

Of course, they're big when you choose to have so many people without a job needing support. He puts these numbers into context by comparing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, commonly referred to as food stamps in the US) expenditure to the much larger amounts given out in corporate welfare. Here is Baker's summary of the gains possible from reversing these five neoliberal policies which support the wealthy, with a comparison to the amount spent on the main US income-support programme (high then low estimates of savings in the right two columns):

*TARP = Troubled Asset Relief Program

US Drugs Cost Twice As Much As In Other Wealthy Countries

As an example of these calculations, the savings from removing the excessive cost of patents and copyright is an estimate of the "rent", a term which describes excess profits extracted in comparison to the most efficient alternative. Drug patents, for example, are replaced by competitive State-managed research funds. The cost of US drugs has increased from 0.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1975 to 2.3% in 2016.

Overall, the US spends roughly twice the average per person as other wealthy countries; that's $US10,300 per person per year. Scarily, in the US they want more financial waste though. There is a push to privatise the delivery of social security payments, despite privately-run defined contribution pensions costing an annual average annual of 0.95% of the assets, while the federal-run Thrift Savings Plan costs just 0.29% of assets.

Baker is pretty straight-up about the tendency of economists to cherry-pick arguments and mathematical models to get the results which benefit them. And he also walks his talk - you can download this book for free from his Website (which includes a sub-page for his two rescued dogs!). Here's a good public summary from Baker, or if you prefer an interview-style introduction to his experiences as an independent economist there's one here. GOING INFINITE This book, both the story and the author, really made me mad. Here's what the Guardian review said: "When the stories of our times are told, there will be no more seminal documents than the books of Michael Lewis". I don't agree. Certainly, he has great access and storytelling, but he's too attached to the inside story here compared to his earlier "The Big Short"*, where he was clearer about the deceptive practises of US-based hedge funds, mortgage lenders and ratings agencies. Jeremy Agar reviewed the book in* Watchdog 131, December 2012 and the film in Watchdog 141, April 2016 Ed.

So, here's the story told in "Going Infinite": a technically bright young guy called Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) with zero people skills or empathy makes one of the largest fortunes in the world in three years by a) starting both a crypto exchange (FTX) and a separate crypto trading company (Alameda Research) which buys cryptocurrency cheap in one country and sells it dear seconds later in another b) ignoring the law c) having no management or accounting oversight d) paying millions to social influencers, politicians and promoters of pandemic management.

Sam Does Whatever He Wants

There was no organisation chart or clear role - "Sam doesn't like them" - and Sam does whatever he wants. At one stage he promised to invest $US5 billion with K5 Global, an investment company co-founded by a Hollywood agent turned investment manager named Michael Kives, without talking to anyone in FTX (Kives personally got $US125 million). And money moved freely between FTX and Alameda Research, run by his girlfriend Caroline Ellison.

"It's unclear if we even have to have an actual board of directors" SBF told Lewis, "but we get suspicious glances if we don't have one, so we have something with three people on it". He admitted he couldn't recall the names of the other two people. "I knew who they were three months ago,"" he said. "It might have changed. The main job requirement is they don't mind DocuSigning at three a.m. DocuSigning is the main job".

TSBF's take on buying political influence: "It just seems like there isn't enough money in politics, people are underdoing it". The US has steadily reduced the transparency of political funding, so that people and corporations can donate unlimited sums to campaigns and political action committee (PAC) funds, influencing an annual Government spend of $US15 trillion without public visibility.

One day they find $US400 million has "leaked", and no-one knows where. The craziness continues. In 2023, after crypto prices crash, they find $US6 billion is missing; that's the customer-deposits money. Public denials are made, while in desperation they approach a rival to take them over. He tweets the news they are bankrupt. Everyone exits their tax-free Bahamas base overnight, and a further $US450 million in crypto exits the wallets of FTX in a "hack" which was likely an inside job. Just one person, Sam Bankman-Fried, is arrested.

Bankman-Fried was charged with seven counts of fraud and related offences and extradited from the Bahamas to the US. Initially, he was released on $US250 million bail, the highest bail amount in US criminal history. However, he was subsequently ruled to have breached his bail conditions, meaning he was imprisoned awaiting trial. That was held in November 2023 and he was convicted on all seven charges. In March 2024 he was sentenced to 25 years' prison. Ed.

Author Crosses The Line

So, the story and the people make you mad, but the author's approach too. Lewis crosses the line between telling SBF's story and buying it. To give just one telling example: Lewis compares John Ray, the man who coordinated the forensic assessment of FTX's bankruptcy, to an "amateur archaeologist" - despite his long experience which includes doing the same for Enron* - and offers his own opinion that it will be difficult to successfully prosecute SBF. *See Jeremy Agar's review of "Enron: The Smartest Guys In The Room" in Watchdog 111, April 2006. Ed.

I was left feeling that the United States has crossed a line too and is now a fake country, if by country we mean a Government which mainly says what it means and has an effective legal system. In the US, as long as enough people make enough money you can do what you want with no consequences, then make a token arrest and carry on to the next scam.

The trouble is this money is being taken from around the world, back to America; from average crypto buyers to a tiny few market-manipulators. It's global theft, without consequences. A replay of the subprime crisis, where totally corrupt US financial companies created portfolios of unpayable housing loans, then knowingly sold them on to European companies as the default rate rose - again with no substantial legal or financial consequences.

Ironically, Sam drew bright young analysts into the company by selling them his spin about "effective altruism" - don't be a doctor or a lawyer, anyone can do that. Make a huge amount of money with me, so you have so much you are able to reshape a better world - while ignoring laws and ethics to get there. Quote from their "engineer" and key coder for the crypto trading system: "That's where I learned what the law is; the law is what happens, not what is written". If you can get away with it, it's legal. What a fine new world they'd have made.

If you want to learn a lot more about the crypto world, you will find some of it in this review. And Wikipedia has a great summary of crypto's abuses, fraud and systemic risk (after the descriptive introduction) here. I particularly liked this point: "Bitcoin has been characterised as a speculative bubble by eight winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science".

LABOUR, POWER, AND STRATEGY This is not a perfect book for its purpose. It's a bit crusty, aimed at union activists in the US. There, corporate abuse of labour laws is so widespread, long-term activists are perhaps more steeped in hard-core labour history, with a greater tolerance for jargon like "associative vs strategic organising". But then again, what political or economic book is perfect? If we had all those answers, our world wouldn't be in such a mess.

Why I liked this book was it raised the critical question: How can we make unions stronger? The authors discuss the value of strategically targeting industrial action in support of the broader struggle to revive union power. An introductory discussion between the editors and John Womack is followed by responses from ten contributors with experience in labour organising and research, finishing with reflections on those comments from Womack.

"No matter what workers are mad about, unhappy about, feel abused about, it doesn't matter until they can actually get real leverage over production, the leverage to make their struggle effective; without that material power your struggle won't get you very far for long". Beyond that specific suggestion and the very US-centric discussion in the book, the debating format also gets you thinking about what other strategic approaches might strengthen union power, so I'll return to that question after reviewing the book.

How To Revive A Shrinking Labour Movement

This is an urgent question in the US, with only about 10% of the workforce formally organised and the proportion getting smaller every year. In the private sector, it's reached crisis level at 6% (NZ coverage is 14% according to the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment - MBIE). Yet 71% of the US population approves of unions and half of all non-union workers want to be in a union. In the US employers can openly engage in union busting, for example firing organisers during membership drives, and inadequate labour laws let them get away with it. Many are prosecuted every year but the fines are less than company wage savings, so on it goes.

Womack is interested in "industrially strategic positions" that hold the most power in the production process. Historically, cases like the successful 1936/37 United Auto Workers' strike at the critical General Motors parts-stamping plants in Flint, Michigan, had led to breakthroughs in organising the auto sector.

He points to those workers in today's just-in-time production or distribution process who can target "choke points". Workers in a production or distribution process are usually involved in several technologies that mesh together and which may create critical links that can be targeted to force concessions from employers.

This is not just a top-down research process for the unions. Involvement of workers brings in important knowledge learnt on the job, as well as gaining buy-in for action. He also emphasises that if broad swaths of society are not organised around, and in support of, the workers at the heart of key choke points, even technically strategic workers will likely fail.

After the editors' interview with Womack, the ten invited responses raise a range of related issues, including:

And since the book's publication, other reviewers have raised important questions like:

Strategic Questions For NZ

In our New Zealand context, other strategic questions might be relevant. Here are a few which occurred to me, and I'm sure you have your own:

"Labour, Power, and Strategy" is available as a PDF e-Book for $US9. To close, here is an online discussion of the book with Q&A from an audience of mainly young US unionists:

THE LAUNDROMAT (Netflix) "The Laundromat" is Soderbergh's admirable attempt to explain the difficult topic of the shell companies used by the rich to hide ownership and evade taxes. The movie mirrors real life by profiling a series of rich villains, many of whom you'll recognise from the news and each with their own reasons for hiding their ill-gotten gains.

Unfortunately, these ever-changing segments mean the movie is not very involving, but it will make you both mad and concerned. You could follow it up with this excellent interview with the original whistleblower in 2022, when he again contacted journalists to emphasise the abuse of shell companies by modern fascists, notably Putin:

Extract: You have remained silent now for six years. Why do you want to speak up now? THE CLIMATE BOOK "The climate crisis has shown that the unrestrained pursuit of self-interest does not serve

the common good. Adam Smith's invisible hand - the idea that free markets lead to efficiency

as if consciously guided - is invisible because it is not there". "The Climate Book" provides a very effective overview on the threat of global warming. The book is divided into five parts: "How Climate Works," "How Our Planet Is Changing," "How It Affects Us," "What We've Done About It," and "What We Must Do Now." And beyond explaining all that, the book clearly has an overall goal to recruit and educate climate activists, which it does well. One hundred authors contribute 90 short pieces, and they're not just any authors but experts in their field. Thunberg provides coherence with a series of linking essays, highlighting key points and, just as importantly, showing her frustration to emphasise where we have to do better.

The result is a very readable book on a complex subject, with short summaries for each of the key issues. You can dip into those which interest you and skip others. If you're like me, trusting the science but unable to explain it, you'll learn a lot. What exactly is the carbon cycle? What do we mean by zero carbon? How are carbon monoxide and methane different? How does global inequality fit in? And of course, what are the priorities for change: personally, nationally and internationally?

Here are a few interesting examples of worthwhile facts I learned: The last big mass extinction was 252 million years ago at the end of the Permian period, long before dinosaurs. It nearly ended complex life forms on earth, which were then mostly diverse marine species living in temperatures similar to today. Carbon dioxide blasting out of Siberian volcanoes raised the air temperature of the planet by ten degrees centigrade; rising water temperatures followed, reducing the ability of the ocean to hold oxygen and support life.

Earth took ten million years to recover, beginning again without trees on land or coral reefs in the sea. More recently, a temperature rise of five degrees after the last ice age raised the sea level by 110 metres; and there is still enough ice on the Earth today to raise the sea level by 65 metres. Oceans have absorbed 90% of the extra heat on our planet, but because water is much denser than the atmosphere, the air temperature rise at sea level is just 0.9 degrees since the late 19th Century, compared to 1.9 degrees for temperatures over land.

Since the temperature-change targets we talk about from global warming are a combination of land and sea air temperatures, that 1.5 degrees average target means temperatures over land will have warmed by about 2.4 degrees - and since Northern Hemisphere temperatures drop due to ocean current changes, the average rise for the rest of us will be even higher than 2.4 degrees.

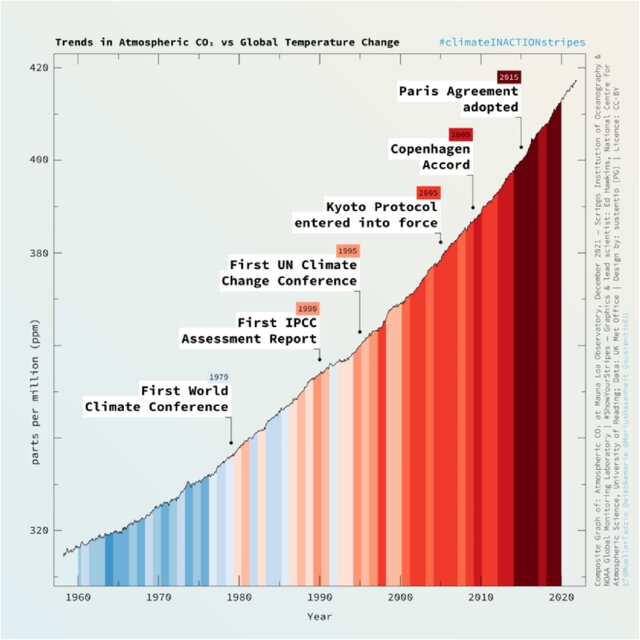

The carbon cycle is long, so change takes a long time. Forty years after carbon dioxide is emitted, 50% is still in the atmosphere, so the effects of carbon emissions are cumulative. That takes a long time to reverse, so carbon cuts are the urgent priority. Reductions of methane have a more immediate and short-term impact on temperatures.

Radical Cuts Needed

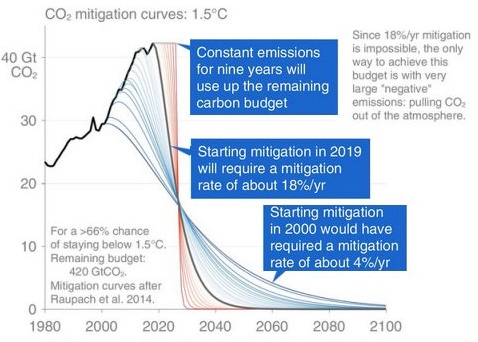

Global carbon management today refers to a "carbon budget", which is the amount of carbon dioxide we can collectively emit to retain a 67% chance of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees - but that accounting began in the 1980s and 90% of those “budget” emissions have already entered our atmosphere and oceans. The chart below shows the radical level of cuts needed today to meet the 1.5 degrees target, given the lack of action to date. Can anyone look at this and believe we will make it? We will need radically more popular power than we have seen to date to get political action.

The 1997 Kyoto Agreement did not require emissions reductions from developing countries, so to reach the 1.5 degrees target wealthy countries need to cut fossil fuel use completely by 2030, or by 2035 to 2040 for two degrees (Kevin Andersen).

Rich people in rich countries contribute much more to global warming than poor people. The lifestyles of the top 1% create twice the emissions of the bottom 50%; if the top 10% of global emitters reduced their carbon footprint to the level of the average European Union citizen, and the other 90% did nothing, global emissions would fall by around one third. Equity helps the planet, so why does equity receive so little discussion? The businessmen, professors, policy makers, journalists, lawyers and senior civil servants who shape these policies all live in the top 1% of global emitters.

The modern economies and wealth of today's rich countries are built on their past emissions and contributions to global warming; an equitable response means rich countries transferring investment to poor countries, who will suffer the most from global warming. Note also that the wording of current agreements does not acknowledge that much of the emissions in developing countries are the result of foreign-owned production.

One point made very clear in "The Climate Book" is that current Government accounting for climate change is deceptive. This is a pretty important point once you've absorbed the Chart 1 above, because you know a) Doing what we're currently doing won't be enough to limit warming to 1.5 degrees and b) We aren't even doing what we say we're doing.

The article by Alexandra Urisman Otto was a refreshing read. Starting as a complacent crime reporter assigned to interview Thunberg, she later realised the seriousness of our challenge and did the work to look behind Sweden's official figures. When the loopholes were corrected in the country's annual carbon accounting, a widely trumpeted reduction became an embarrassing increase.

It turns out Sweden's actual annual emissions are at least three times the number it reports to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Scientists interviewed by Alexandra advise that if all countries fail to establish their targets as Sweden has done, global heating was heading for between 2.5 and three degrees.

Reading about possible changes in the food chain was one of the most positive reads. Plant-based diets do the least harm, followed by dairy, eggs, poultry, pork and net-caught fish. A comprehensive change to plant-based food, reducing over-consumption and waste, and improving the food supply chain could actually meet the 1.5 degree- target - if we were able to make such a radical change happen overnight. Another was the analysis of driving. Introducing a speed limit of 130 kilometres per hour in Germany alone would lower carbon emissions by 1.9 million tons annually, more than the total of the 60 lowest emitting countries; a limit of 100kph would save 5.4 million tons (86 countries).

The overarching need for climate justice is an important part of "The Climate Book." Four contributions made the case for a genuine Emergency Response (Seth Klein; "learn from covid" and "create new economic institutions which get the job done"); Degrowth (Jason Hickel; "ask which parts of the economy we need to improve, don't grow the whole economy"); Redistribution (Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty; "polluter pays" and "no worker left behind"); and Reparations (Olúfhemi O. Téíwò; "today's world came by way of the global racial empire" and "true world making calls for us to rebuild the system itself").

So, What Is To Be Done?

After an honest accounting of emissions and impacts, the next priority emphasised by Thunberg is an honest "magic bullet" solutions like carbon capture and storage, biofuels, recycling, and geoengineering; the sort of solutions championed by oil companies. The only realistic solutions are already proven technologies, like wind and solar, as well as possible, if politically daunting, changes in human behaviour.

And in this time of inadequate responses, political scientist Erica Chenoweth observes that a determined minority can be enough to tip a society toward change. She operationally defines "determined minority" as 25% of the population. A higher proportion of most nations already polls as "alarmed" about climate change, but we need to see them in action.

To end, the book provides a short list of things you personally can do:

NZ Suggestions

Locally, Forest and Bird recommends removing pine headed for clear-felling from our Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and replacing it with permanent native forests: Local group Our Climate Declaration debates the pros and cons for New Zealand's ETS: And here is a link outlining a proposed Social Europe plan for zero carbon by 2050.

LEGACY OF VIOLENCE "Empire was not just a few threads in Britain's national cloth. "Britain was the nation boasting history's largest empire, whose heroes and justifications led many astray. The legacies Britain's empire left behind have had significant bearings on a quarter of the world's landmass, "I remember the shock I felt when I first learned of the scale and intentionality of document destruction and removal in the empire. Today I'm left wondering how many Britons really know about the burning and laundering of their nation's past. How many of them realise the role their heroes and expert civil servants played in trying to manipulate how history would be written?"

This is an important book providing new insights into the brutality of colonialism. By presenting newly uncovered evidence it will shift your understanding of many familiar episodes in the version of history with which we have grown up. Author Caroline Elkins won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Non-Fiction as a young US scholar with her previous book, "Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story Of Britain's Gulag In Kenya", in which she documented the confining of around 1.5 million Kenyans in a network of detention camps and heavily patrolled villages.

Polarised academics split, with those preferring the traditional portrayal of English empire as relatively liberal accusing Elkins of sloppy research and reliance on dubious oral testimonies. Her job was on the line, so she kept her head down and began work on a new book - "Legacy Of Violence" - to re-establish her reputation and chances of a tenured US job.

Taking The Empire To Court

Then the phone rang, asking her to join a London legal case as expert witness for reparations to elderly Kenyans who had been tortured in those detention camps. She wanted justice, said yes - and more controversy and criticism followed. But unknown to the public, a vast colonial archive documenting the methods used on the front lines of the empire had been hidden away and its existence denied, exactly because it did not fit with the official line. After independence the Kenyan government, aware that official records were flown to England, requested their return but was met with denials.

Then, in 2010, when the compensation case lodged a statement with the court referring directly to the same 1,500 files spirited out of Kenya, the British government finally acknowledged what it had known all along - the records were in a high-security storage facility shared by the Foreign Office and intelligence agencies MI5 and MI6. And there was much more. The repository held files similarly removed from a total of 37 former British colonies at the end of the empire. During the trial these documents confirmed oral stories of administrative and military brutality in Kenya, and now inform Elkins' latest book, "Legacy Of Violence".

Although her main focus is on documenting administrative inhumanity and military violence, Elkins also does a good job of linking in the ruthless economic extraction from subjugated nations which underpinned the Empire. To take just one telling example - most of us have heard of an incident from early in the English conquest of India referred to as "the Black Hole of Calcutta" but few know the context.

The British East India company, many of whose shareholders were English MPs, had made treaties, negotiated trading rights, levied taxes and maintained an army in Bengal, then the richest state in India. When war started between France and Britain in 1756, the company broke its local agreements by fortifying its trading post in Calcutta; the ruler of Bengal responded by seizing the British fort, imprisoning all remaining Europeans.

In the widely reported account of a survivor, 145 captured British soldiers were imprisoned in a cell 18 by 14 feet with two tiny windows; only 23 survived. Quote: "This scene of misery proved entertainment to the wretches without. They took care to keep us supplied with water, that they might have the satisfaction of seeing us fight for it ... and held up lights to the bars that they might lose no part of the inhuman diversion".

Later assessments suggest the account was exaggerated, with 39 prisoners more likely and battle wounds causing most of the 18 deaths, but that is not the point. The lurid version "went viral" in England because it served the private profits of the Empire; the Company's response was a victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, taking control of Bengal; and the underlying cause of conflict was the company's ruthless economic extraction.

After gaining the right to collect taxes from the Mughal nawab, Bengal's leader, the Company took £1.65 million annually in tax revenue - £400,000 of which went to the British government as an inducement to ignore their private corruption. That tax revenue dried up in five years as farmers were forced to sell cattle and eat seed-grain; an estimated one-third of Bengal's 30 million people died in the resulting famine - that's ten million people who died for England's profits.

Meanwhile these corrupt champions of the Empire like Robert Clive ("Clive of India") were viewed as heroes at home because they won battles and brought home riches. Foreigners were portrayed as inferior races incapable of governing themselves, a convenient rationale to hide England's exploitation. Today, evidence is slowly shifting myths and prejudices, but nearly 60% of the British population still believes "the British Empire was something to be proud of".

Dutch historian Niels Boender, discussing a Channel 4 documentary looking at the colonial repression in Kenya, noted the disconnect between the current public debate and the expert research and discussion. "You find that the (public) debate is sort of stuck... 50 years in the past", he said: "In the public level, the debate is: 'Was the empire good?' Whereas we're debating 'How bad was it?' and 'In what ways was it bad?'"

No doubt the British policy of incinerating documents that "might embarrass Her Majesty's Government" or "members of the Police, military forces, public servants or others" has played a role in this mass ignorance. A reputed 3.5 tons of paperwork were destroyed in Kenya. But the really scary part of this book is watching the brutal practices developed to enforce Empire spread and mutate into worse horrors as those techniques are refined in each successive colonial crisis - community destruction, executions, torture, abuse of women, detention camps, the weaponry for massacres. And there were over 250 separate armed conflicts in the British Empire in the 1800s, with at least one in any given year.

In The Beginning

In the early 19th Century Britain preferred informal mechanisms like treaties to ensure markets for its trade and capital but, as the century progressed, foreign competition forced British occupations and formal rule across its territories. This was more expensive, since violence was required to gain and maintain political control of previously independent nations.

Rudyard Kipling called these conflicts the "savage wars of peace" - the sort of imagery the British lapped up. Political philosophers like John Stuart Mill and James Fitzjames Stephen claimed "good government would reform backward populations. Imposing the rule of (British) law was Pax Britannica's most potent tool".

That same law and governing procedures directly facilitated underpayment for resources acquired in the colonies, codified and prescribed the racial hierarchy, curtailed freedoms, expropriated land and property, and ensured a steady stream of underpaid labour for foreign-owned mines and plantations. But the ordinary codes and regulations were not enough to quell the rebellions created by extractive colonisation, so officials also developed parallel forms of martial law and states of emergency. Decision-making was left to the local administrators, who interpreted when State violence was necessary, and at what level, to protect the State and preserve its' laws.

This characteristic process - incrementally legalising, bureaucratising and legitimating exceptional State violence whenever ordinary laws proved insufficient to maintain order and control - is referred to as "legalised lawlessness" by the author to highlight the pattern of abuse repeated across time and the empire. Legalised lawlessness supported a culture where barbaric excess was acceptable as a response to crises - massacres, executions, torture and terror, sexual assault, mass imprisonment, hard labour and undernourishment, deportation, forced migration. Increasingly, the use of these "special powers" and emergency regulations were adopted to manage the realm through crises.

Deliberate State Terrorism

Here is a young Winston Churchill describing the British response after their punitive raid on the Mamund Valley on India's North-West Frontier in 1897 was unexpectedly repelled: "We proceeded systematically, village by village, and we destroyed the houses, filled up the wells, blew down the towers, cut down the great shady trees, burned the crops and broke the reservoirs in punitive devastation. At the end of a fortnight the valley was a desert, and honour was satisfied".

Early control largely benefited from military superiority. In 1898 troops equipped with machine guns and modern rifles killed at least 10,000 Sudanese followers of Muslim leader Muhammad Ahmad at the Battle of Omdurman, losing only 47 soldiers. Colonial military doctrine became codified, as in Callwell's "Small Wars: Their Principles And Practices". He argued that troops in wars against "uncivilised" and "savage" populations needed a different set of rules.

Callwell claimed both the "moral force of civilisation" while advocating the need to demonstrate European superiority by "teaching the savage peoples a lesson they will not forget". Waging total destruction brought more than strategic advantages; the "enemy must be made to feel a moral inferiority throughout... (Fanatics and savages) must be thoroughly brought to book and cowed or they will rise again".

An unwritten rule of empire was that colonies should also be fiscally self-sufficient, so the extraction of wealth for private profit also had to pay for the cost of the occupying army and administration which supported it. The Boer War in South Africa threatened that formula, as it degenerated into an all-out assault on an entire ethnic population when the rural Boers (white Afrikaaners) proved adept at guerilla resistance. The prize which made it worthwhile was ensuring a supply of gold to back the pound's dominance as the world's currency and the profits of Britain's banks

The whole country was divided up with barbed-wire fences, while a scorched-earth policy burned crops and dumped salt to prevent future cultivation, and 30,000 prisoners of war were deported to remote corners of the empire. The state of emergency was used to keep critical witnesses from entering the country and seeing the inhumanity of the British concentration camps.

Camps for Black Africans were worse than those for the Boers, with forced labour on reduced rations creating death rates of 10%. But the British administrators documented their lessons from these camps - how to isolate the sick from the healthy, so death rates were not so extreme and English opposition could be marginalised.

Eventually the strength of Boer opposition brought a negotiated settlement where the British prioritised optimal gold production. Races were administratively separated and cheap black labour ensured, alongside protection for poor whites and new land regulations - the foundations for apartheid in South Africa.

Civilisation And Savages

During the 19th Century the most prominent British international lawyer, John Westlake, supported the view that international law "regulates, for the mutual benefit of the civilised states, the claims which they make to sovereignty over their region and leaves the treatment of the natives to the conscience of the state to which sovereignty is awarded". In his view, a "native" chief could not transfer sovereignty, because that was purely a European concept of which "natives" had no understanding.

By this time though, modern international humanitarian law was trying to set some limits on both colonial and military insanity. I was interested to read how the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention on "humane" wars began - in 1859 a Swiss merchant travelling to see Napoleon III on business witnessed a battle between French and Austrian armies in northern Italy. Three years later he published a book about his memories of walking among the 40,000 dead and neglected wounded they left behind.

Dumdum bullets had been adopted by the British in India and Sudan because their explosive trajectory through bodies killed and maimed more effectively. At the Hague Conference of 1899, Britain and Luxembourg were the only nations which refused to adopt a ban on their use. Britain later agreed to stop using them in 1902, but colonial forces continued to use them unofficially up to at least the 1930s.

Colonial racial categorisations also underpinned Britain's military during the First World War. Hundreds of thousands of imperial subjects formed the backbone of Britain's military carrier corps (labour corps), with exceptionally high death rates of around 20%. Colonial revenues were also substantial, with India, for example, forsaking 15% of its revenues by 1918.

Before and after WW1, Britain's efforts to contain Irish rebellion turned Ireland into a laboratory of experimental counterinsurgency. The notorious Black and Tans adopted brutal tactics and "reprisals" to try and crush Sinn Féin during Ireland's War of Independence; they were then redeployed to Palestine after the Anglo-Irish settlement. The structure of empire allowed violence to be learnt and refined across borders. The book takes us from India to South Africa to Ireland to Palestine and beyond, with the same cast of characters appearing in each location as the system is perfected.

One grim new factor was the increasing use of "air power". From 1919 onward, aircraft of the newborn Royal Air Force were a far cheaper means of subjugation than armies. They bombed and machine-gunned defenceless people in Afghanistan and India, with no officer more enthusiastic for the task than Arthur "Bomber" Harris. After the Great War, the empire had reached its territorial zenith with the acquisition of the vast new territories of Iraq and Palestine. Having bombed Iraqi villages, Harris moved on to bombing Palestinian villages.

By the time a state of emergency was declared in 1950s' Kenya, the agents of empire had honed a horrifying array of torture techniques, including electric shocks, use of fire and hot coals, inserting snakes, vermin, broken bottles and hot eggs into men's rectums and women's vaginas, crushing bones and teeth, slicing off fingers and castrating men. This direct imposition of violence and creation of violent opposition is only the first, obvious, legacy of the empire.

Reinforcing Race-Based Hierarchies

The second legacy is the destruction of previous complex political balances and forms of governance, so that its' withdrawal created a vacuum and triggered conflict escalation. The third legacy was the co-option of local elites into the lower rungs of the administrative bureaucracy - to collect taxes, compel underpaid and forced labour. This need for divide-and-rule fed the segregation of subject populations on racial lines, shaping not just the colonies but today's post-colonial politics (see my review of "How Civil Wars Start" by Barbara Walter, in Watchdog 163, August 2023, for evidence on the link between racial dominance, autocracy and civil war).

Britain, Palestine And Israel

It's timely to revisit the state of Palestine today, as the Israeli military kill tens of thousands of civilians to preserve its' repressive apartheid state. The British played a key role through the Balfour Declaration of 1917, favouring the creation of a "national home for the Jews". Complex historical imbalances were pushed further towards community conflict by Jewish immigration and land acquisition.

Into this explosive mix, which previously had just 20 police officers for a population of over 600,000, Britain sent a mix of post-war Army Auxiliaries and Black and Tans. None had local knowledge and few spoke even basic Arabic. Policing rapidly became militarised, with routine beatings and torture. Palestinians as the most active political protestors became the main target of this violence, which culminated in the Arab Revolt and general strike of 1936.

The British response was draconian, with reports of widespread beatings and torture, ransacking and looting homes, deportations, disappearances and executions, denial of food and water to civilians, rapes of women and girls, and destruction of livestock. One illustrative example: the British Army used gelignite to blow up 250 multi-resident Arab homes to improve military access to rebel areas in the old city of Jaffa, air-dropping leaflets on the morning of the destruction warning residents to vacate and find new homes.

It got worse. Intelligence Officer Orde Wingate introduced Special Night Squads, with some village raids lining up Arab men and shooting dead every 15th person; women and children were killed in their sleep. And Wingate included Jewish police in his squads, further undermining any future peace. A quote from Wingate makes his influence clear: "The Jews will provide better soldiery than ours. We have only to train it. They will equip it. Palestine is essential to our empire - our Empire is essential to England - England is essential to world peace. Islam is out of it".

Managing Public Perceptions By Hiding The Truth

A critical question raised by this story of Empire is the right to deny and restrict access to the truth. Since acts of systematised violence, often ordered from the very top, had to be removed from the imperial record, Britain's control of official narratives required an extraordinary level of document destruction, forgery, coordination, official silence and strategic confusion. In opening up this story, the book highlights the continuing importance today of access to the truth to dispel narratives of convenience. The imprisonment of Wikileak's Julian Assange is just one example.

Part 2 Next Watchdog (166, August 2024)

This is a book of 875 pages and small type. I have reviewed seven chapters out of 14 here, up to the Second World War, as they focus on the internal dynamics of violence across Britain's empire. During and after the Second World War the international balance of power is radically different, with Britain no longer strong enough to hold back its colonies, so I'll write a second review covering that period in the next Watchdog.

Overall, I thought it was a great book which increased my understanding of my own history. The language is a little academic in places and the story spends a little too much time on the clash of ideas behind colonial violence (e.g. the evolution and contradictions of liberalism) - but these are minor weaknesses.

Opening up the truth behind the Empire's myths is critically important because, as the stories here show over and over, the abusers and their practices move on and mutate to affect the response to each new colonial crisis - and that violent response fed into post-colonial entrenchment of racial divisions and reliance on political, economic and military violence.

A New History Of Aotearoa

In concluding I'd like to also highlight another book which opens up history, this time our own. "History Of New Zealand And Its' Inhabitants" was written by Dom Felice Vaggioli in 1896 and published in Italy but destroyed by the British. A found copy was translated to English in 2010 by John Crockett and reprinted in 2023 by Otago University Press.

This new view of Aotearoa's colonisation is a breath of fresh air because it speaks of the issues of the times, but favours the Māori perspective over the English. The actions of whalers and missionaries alike in manipulating local chiefs to sign over lands for a pittance are documented, as is the lack of local and English interest or legal responses to preserve Māori land. Your library should have a copy.

On February 29, 2024, the Northern Advocate highlighted an early land "sale" (fraud) agreement revealed in a recent English auction catalogue. The 1826 document transfers ownership of three islands in the Hauraki gulf for nine guns and a barrel of gunpowder, and was facilitated by a missionary as translator. These practices were documented as standard by Vaggioli in his book back in 1896.

REVIEW

- Makareta Tawaroa UNBOTTLED In just four decades, bottled water has been transformed from a luxury niche item into a ubiquitous consumer product, representing a $US300 billion market dominated by global corporations. It sits at the convergence of a mounting ecological crisis of single-use plastic waste and climate change, a social crisis of affordable access to safe drinking water, and a struggle over the fate of public water systems.

Bottled water is now the most consumed packaged drink. So why are we drinking so much of it and what's the environmental cost? In his book, "Unbottled: The Fight Against Plastic Water And For Water Justice", sociologist Daniel Jaffee explores these questions. While it is written from an American perspective, it nevertheless has increasing relevance to our way of life here in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Social Justice Crises

Bottled water is not just a controversial product with lots of well-known negative environmental impacts, it's connected to a social justice crisis of uneven access to safe and affordable water around the world. For over a century, in most parts of the world, the provision of public drinking water has been a central function of local governments. Their legacy and commitment were to public health and a good quality service. That same level of commitment no longer exists.

Bottled Water - A Medium-Term Solution

In many developing countries where there is no safe tap water supply, the bottled water industry is presenting itself as a "medium-term solution", says Jaffee. Governments and authorities, therefore, are delaying addressing the lack of a public water supply. Wherever there is a substantial percentage of the population that do not have access to tap water, the reliance on packaged water will increase. This gives governments an escape clause, giving them permission to opt out of their obligation and responsibility to expand water services. This weakens the urgency of fixing broken drinking water infrastructure and feeds a vicious cycle of deterioration and distrust in tap water and then disinvestment.

A Priority

"Allowing bottled water to serve as a replacement for safe-to-drink tap water weakens the political impetus for governments to invest in maintaining and restoring public water systems", Jaffee says. Because water is unevenly distributed, governments and international institutions need to prioritise it. It is not right for people, particularly the poorest, to live permanently in a costly packaged-water world.

Controversially, the United Nations has reclassified packaged water "as an improved drinking-water source". But who for, how long, and at what cost? In wealthy countries, a combination of opportunistic marketing, increased demand for convenience and trending ideas about hydration and health, have driven the bottled water boom. There's evidence that one in five Americans now completely avoids drinking tap water due to subtle or even overt persuasion from that industry.

Tap Water War

There's a bottled water company in the US, whose ad portrays a corroded public water pipe and says something to the effect of: "Your tap water could be contaminated with bacteria and heavy metals". There is now a war on tap water. Increasing populations are turning away from tap water. Compared to public water supply, the bottled water industry is only "lightly" regulated, Jaffee says.

"Very often consumers are unable to find out basic information about whether bottled water has had contamination instances or whether it has been recalled". Peer-reviewed studies show that microplastic problems are more significant in bottled water. For example, someone consuming solely bottled water in the US would consume 22 times more microplastic fragments than someone consuming tap water only. There are also leaching issues as well so it's an uneven playing field.

Regulatory Regime - Soft On Bottled Water Industry

Furthermore, public water authorities are required to be more transparent and rigorous than the bottled water industry, which is often regulated as a foodstuff, and has a much weaker regulatory regime. It's also difficult to find out good information about the content and the contaminants contained in bottled water. It's an uneven playing field. Then there's the plastic pollution factor. "Studies show that the energy impact of a litre of bottled water is between 1,000 to 2,000 times that of a litre of public tap water. With up to 700 billion single-serve plastic containers disposed of each year, it's clear we have a global plastic pollution emergency", Jaffee says.

The great majority of plastics end up either in landfills or enter the marine or aquatic environment. Beverage bottles are half of the marine pollution problem at this point. The global single-use plastics problem will never be solved without first addressing single-use plastic bottled water. While the beverage industry is "pretty wedded to single-use plastics as its business model," Pepsi and Coca Cola are being encouraged to sell beverages in refillable, returnable and durable plastic containers.

Returnable, Reuseable Plastic Containers - More Cost Effective

There has been a lot of research done on this... if the entire global beverage industry used returnable reusable plastic containers, which could be used, say, 40 or 50 times each, it would cut raw material use and waste by 40% and greenhouse gas emissions by half. "That's pretty significant." says Jaffee. In the US bottled water market, Jaffee says there is a hopeful "counter-trend" with 2023's sales falling by 1% for the first time in over a decade, while in Aotearoa sales are also projected to decline in future years.

Water - Protect And Revitalise

The return to public drinking water is a way of reclaiming a shared public good that our forebears funded in the form of water rates and taxes and should be protected and revitalised for the future. In "Unbottled", Daniel Jaffee offers a superbly researched argument that our growing dependence on bottled water is not only creating a major environmental crisis but also weakens the whole notion of public water services - thereby undermining the human right to water for all. It explores widely the bottled water's impact on social justice and sustainability.

Jaffee draws on extensive interviews with activists, residents, public officials, and other participants, and on how diverse movements are fighting back. He touches on issues, ranging from bottled water's role in unsafe tap water crises to groundwater extraction for bottling in rural communities. Water is a public good and requires substantial public investment.

Recommended

Given water's meteoric growth as a commodity, this book gives us some ideas on how this will affect social inequality, sustainability, and the human right to water. "Unbottled" is a great book and a must read for those who are fighting against plastic water and for water justice.

REVIEW

- Dick Keller DOPPELGANGER Jeremy Agar reviewed "No Logo" in Watchdog 98 (December 2001); "The Shock Doctrine" in 117 (April 2008); and "This Changes Everything" in 138 (April 2015) Ed.

A doppelganger is a double, a person very much like another person, or even oneself, or somehow being confused with oneself by others. Likely with some unexpected reactions by oneself or others to this duo. Or an individual with a split personality like Jekyll and Hyde. "For Freud, doppelgangers represented paths not taken, choices not made". Or multiverse stories like depicted in the recent movie "Everything, Everywhere, All At Once".