PRIVATISATION, INEQUALITY AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

- Bill Rosenberg

This is Bill's chapter for a new book "Privatisation, Plunder And Neoliberalism: Essays In Political Alternatives For Aotearoa New Zealand". Introduction by Dick Werry. Published by Steele Roberts. Ed.

If neoliberalism is defined as how the Mont Pelerin Society sees the world, then privatisation of public assets and services is central to its aims. This international society, which met in Christchurch in 1989 to hear from Roger Douglas how he set about his radical changes starting in 1984, believes that there is "danger in the expansion of Government, not least in State welfare, in the power of trade unions and business monopoly, and in the continuing threat and reality of inflation".1 Privatisation is a way to shrink the Government by handing it to private interests.

John Williamson was the economist who in 1989 first spelled out the "Washington Consensus", a ten-point programme which many considered neoliberalism in practice. Williamson later denied it was neoliberal, which he defined as the "doctrines propagated by the Mont Pelerin Society". Nonetheless he stated that his eighth point, privatisation, "was Margaret Thatcher's principal personal contribution to economic policy worldwide. It is the only doctrine for which one can trace a specifically neoliberal origin that made it to my list of ten desirable reforms".2

Aotearoa Has Had An Appalling Experience Of Privatisations

The sales of New Zealand Rail and Air New Zealand went so wrong that renationalisation was an imperative. Among the others there was the abject failure of Telecom to develop our telecommunications system despite monopoly profits, most of which went overseas with little reinvestment; the handover of our banking system to four Australian banks through the sale of the community-owned Trustee Savings Banks, the Bank of New Zealand and Postbank, only marginally remedied to date by the creation of Kiwibank.

Plus, the scandalous bargain price sale of the Government Printing Office to kick start the empire of one of the wealthiest men in Aotearoa, Graeme Hart; continuing dysfunction in the partially privatised electricity system which created blackouts, huge price increases, inadequate investment and still fails to provide reasonably priced and secure power.

Not to mention conferral of private duopoly status in commercial radio through the sale of Radio New Zealand's commercial stations; the loss of huge potential for further processing in the sale of forestry cutting rights; and Housing Corporation mortgagees feeling defrauded when their mortgages were sold to private financiers. Many of the problems these privatisations were supposed to solve are still haunting us.

Telecom

To give just two examples of the effect on the liabilities of Aotearoa: the Ameritech/Bell Atlantic/Fay-Richwhite-Gibbs-Farmer syndicate bought Telecom for $4.25 billion in July 1990. At the time, the company was in a strong financial position with shareholder funds of $2.5 billion and owing $1.2 billion in debt. Its financial position weakened considerably over the next several years under its new ownership despite cost-cutting. Shareholder funds declined because of large dividend and capital payments to its shareholders.

When the consortium sold out in 1998, it had made a capital profit of $7.2 billion3 in addition to a share of over $4.2 billion in dividends . This added approximately $10 billion to the international liabilities of Aotearoa. Between 1990 and 1998 the company's shareholder funds halved to $1.1 billion by when it was heavily in debt. In the decade from 1995 to 2004, Telecom paid out dividends of $6.7 billion from net earnings declared in Aotearoa of $5.4 billion, of which approximately $5 billion went overseas4.

While the entry of Vodafone (now OneNZ) and 2 Degrees to the telecommunications market forced Telecom, later renamed Spark, to compete, the entry of Aotearoa into high-speed broadband had to be Government initiated and financed, after forcing Telecom to split out its network monopoly into a new company, Chorus. The privatisation of Telecom not only failed to induce it to compete, invest and build our telecommunications infrastructure - which the Government had to do instead - but it added substantially to the country's overseas debt and flows of resources overseas.

New Zealand Rail

The New Zealand Rail sale in 1993 was organised by merchant bankers Fay Richwhite who then proceeded to benefit from it hugely by taking a substantial shareholding - a conflict of interest fit for a post-Soviet state. The main shareholders of the purchaser, TranzRail, were Fay Richwhite, Berkshire Fund and Wisconsin Central of the US, and Alex van Heeren. They bought a company which had been freed of debt by a $1.6 billion injection by the Government. The price was $328 million, of which they paid only $107 million and borrowed the rest.

According to investment analyst Brian Gaynor they "were responsible for stripping out $220.9 million of equity in 1993 and $100 million in 1995"5. By the time they had sold out, they had made total profits of $370 million, mainly tax free because of the lack of capital gains tax, and darkened by accusations of insider trading6. Under Wisconsin's management the safety record was appalling (by 2000, fatal accidents for employees were eight times the national average) and reinvestment and maintenance were abysmal, leaving the operation in a crippled state.

They sold out to Toll of Australia who similarly failed to maintain the system, and who then sold it back to the Government in two tranches for a total of over $700 million plus ongoing costs of several hundred million dollars to repair the rail network and replace the antiquated rolling stock. It is difficult to estimate the total costs to the country, but the total cost to the Government was almost $4 billion7, greatly magnified by the neglect of the private owners. Our transport system is still suffering from the lack of a well-functioning rail service.

The Clark Labour-led government was accused of paying too much for the rail company, and they probably did, but that was just one element of the huge financial and opportunity losses to the people of Aotearoa as a result of the privatisation that were evident well before the renationalisation. The story starkly illustrates the difficulty and cost in reversing privatisation once committed.

Likely To Take Different Forms

There is concern that the National/ACT/New Zealand First Government elected in 2023 will embark on another wave of privatisation. Because many of the commercially viable arms of the State have long been sold, and privatisation is so unpopular, handing Government responsibilities to private interests is likely to take different forms: public-private partnerships and increased provision of public services by publicly funded private suppliers.

As well as central Government moving in these directions, there is pressure on local government to take similar steps. A step before privatisation is commercialisation of provision of public services, with expectations that they should "pay their own way" or make a profit, and increased use of user charges. If they succeed then privatisation becomes viable. The Government has made it clear that all of these steps are in their sights.8

This chapter will first cover what forms privatisation might take, and arguments for and against it. It will cover a little of the background and how a bias towards privatisation is embedded in Government financial rules and accounting systems. Privatisation has been described as "more a political than an economic act" and the chapter will look at the politics of it all. Finally, before concluding, the chapter will briefly look at who benefits and the impact on income and wealth inequality.

What Is Privatisation?

Privatisation can take a wide range of forms. ES Savas, who accurately describes himself as an "internationally known pioneer in and authority on privatisation"9, served in the Reagan Administration and advised on privatisation in the US and the UK. He defines privatisation as "reducing the role of Government or increasing the role of the other institutions of society in producing goods and services and in owning property"10.

Within this wide definition, there is a great variety of privatisation techniques of which the sale of a State function is just one example. Sue Newberry, retired Professor in Accounting at University of Sydney and expatriate New Zealander, has studied the embedding of such techniques in the financial rules created by the New Zealand Treasury.

She quotes Savas to list the techniques. They include complete divestment by sale, donation or liquidation; delegation (limiting the activities of Government) by contract, franchise, grant, voucher, mandate, user charges, PPPs (public-private partnerships); and passive techniques such as running down or cutting services ("load-shedding"), default, withdrawal or deregulation11.

The terminology changes to escape the negative associations with terms as they become unpopular. We are unlikely to be told that a Government is privatising its responsibilities or assets - more likely that it is increasing competition, increasing choice, increasing innovation, devolving responsibilities to the community, producing value for money or strengthening capital markets.

Arguments For And Against

Advocates will argue that Government agencies have never done everything themselves: they have always purchased goods ranging from stationery to buildings, and services ranging from building leases to banking. What is the difference between privatisation and the purchase of goods and services? The critical difference is whether a degree of public control or responsibility has been transferred in the process.

When Telecom was sold, the Government lost most of its ability to ensure that the telecommunications infrastructure of Aotearoa was provided, maintained and developed in the public interest. The Government retained the power to regulate, but that has proven highly problematic and relatively impotent.

When, for example, a school is run in a Public-Private Partnership, the PPP contractor gains powers to decide on aspects of the design of the school, who uses school facilities when the school is not using them and how they are charged for, use of the school for commercial activities such as vending machines, a monopoly position in the provision of building modifications, services and facilities for 25-35 years, and possibly many other aspects.

By contrast, the purchase of pens and paper is unlikely to influence the powers of a Government agency or the service it provides to the public; the lease of a building will be negotiated so that it does not interfere with the agency's public responsibilities and services and is normally for a short enough period that a strongly competitive element is maintained.

Banking services in normal times should not confer influence by the bank, but we have seen in the Global Financial Crisis that began in 2008 that this is a possibility in that the crash of a bank could cripple the functioning of Government and the bank's interests could conflict with what the Government judges to be in the public interest. In addition, the Government is a major source of income to the bank. Perhaps private provision of Government banking services should be revisited.

A critical issue is therefore that of control, and our ability to take action in the public interest to address problems and make improvements in our economy, environment and society, often in the face of powerful forces in the market who can take advantage of their position. State-owned assets have multiple functions, the balance of which will differ in each case. They include

- Preventing excess profits in important services which are a monopoly or are otherwise less than fully competitive;

- Ensuring essential services are provided equitably and affordably

- Providing security of services;

- Social solidarity mechanisms such as ACC (or equivalently perhaps, providing services which are considerably more efficient to provide universally than individually)

- Providing services in the public interest which the private sector is unlikely to provide;

- Providing additional income to the Government.

"Efficiency"

The arguments made for privatisations vary. The most frequent is that of efficiency. Advocates such as self-described PPP "pioneer", Castalia12, which the Government employed to prepare a business case on the merits of school PPPs, appeal to theory to support lower costs. Private owners in a PPP, they say, have an incentive to keep down costs including long term maintenance costs.

The Minister of Finance Bill English asserted in 2010 that private prisons would be 10-20% cheaper than public provision over their lifetimes; in fact, the State had to take back the operation of Mt Eden prison from UK transnational Serco in 2015 after loss of public confidence in its ability to run the prison in a competent and humane way13. We were told that the corporatisation and then privatisation of the electricity system would bring cheaper power and better use of resources. There was a similar story for rail.

However, the claims of financial savings are often weak, and other claims are substituted. Three months after the Minister of Finance was asserting cost savings, the Minister of Corrections, Judith Collins, conceded that for prisons "the building costs were likely to be about the same but ... saving money was not the major reason the Government favoured a public-private partnership"14. Similarly, Castalia acknowledged that the PPPs would provide only "a small improvement in value for money" over the Ministry of Education's current practice15 and as will be seen, even that is in doubt. Some of the lower costs are due to paying staff lower wages and salaries.

The Centre for Public Services in the UK found that staff in private prisons were paid 25% less on average than their State counterparts and had inferior non-pay entitlements16. Castalia wrote that they "assume a PPP contractor (in Aotearoa schools) will improve the efficiency of caretaking and cleaning by 20% including through contracting out and stronger labour bargaining"17.

This in effect becomes a way of forcing down pay for public service staff. It is not an efficiency from an economic viewpoint, as the PPP contractor's gain is the Aotearoa worker's loss. It may or may not be passed on to the Government in lower charges, and it is likely that a significant proportion of the contractor's profits will go overseas, increasing the cost to the economy.

Little of this detail is acknowledged by advocates, but given the weakness of the argument, they increasingly rely on service improvements. "Factors such as innovative rehabilitation or drug and alcohol programmes that private providers might offer were more important" than lower cost said Judith Collins. We now know what actually happened with the Mt Eden privatisation.

The Department of Justice under the Obama Administration in the US was so disenchanted with the private prison safety record including numerous prisoner deaths and lack of cost savings compared to Federal Government facilities that in 2015 it began the process of ending its use of all private prisons - only to be reversed by the Trump Administration. Castalia relies on "improved educational outcomes through better property maintenance and certainty of costs under PPP through better risk management" to recommend PPPs proceeding.

"Public Value" Issue

Even taken at their word, the obvious question is why those benefits (if they indeed exist) cannot be found by the public service either adopting improved practices directly, or contracting experts to advise on them and assist adoption. There is indeed a "public value" issue here - public services should constantly strive to serve the public better - but it is not apparent why privatisation is uniquely placed to resolve that. Indeed, when State operations are sold, it loses the knowledge and practical experience of running those operations making it difficult to resume them or even to supervise effectively their running under private control. This is an important aspect of the hollowing out of the State.

May Not Exist

In fact, these efficiency and service improvement advantages may not exist. Research comparing privatised and public industries produces indecisive and conflicting results as to efficiency. For example, Letza, Smallman and Sun18 review several such studies and conclude that "it seems that the privatisation of public sector enterprises not only does not necessarily lead to an efficient solution for business success, but it also creates many problems and crises, and it is arguable that advocates of privatisation . . . ignore impressive examples of inefficiency, waste, and corruption in the American experience with defence, construction projects, and health care - all mostly produced privately with public dollars".

There are numerous studies from the UK and elsewhere on the failures of PPPs and similar arrangements either to save money or to improve services. An analysis of PPP roading projects in the UK and Spain showed the additional cost of PPP projects over public debt was 30 to 40% of the revenues for the roads19. A study of six Public Finance Initiative schemes in Scotland and England showed returns to investors of from 17 to 23% and suggested "the projects are very poor value for money".

"The Edinburgh Infirmary, Hairmyres and James Watt College could all have been built for half the cost if the money had been borrowed in the normal way from the Government's national loan fund, ... and huge savings could have also been made on the Highland schools, the Perth offices and the Hereford hospital"20.

An investigation by The Independent on Sunday found not only "staggering" costs and wastage - such as a school in Belfast which was closed six years after it was built when pupil numbers halved, yet payments to the contractor were to be £370,000 a year for the next 18 years - but also a failure of ongoing services to meet their promises. An example was "extortionate charges for routine maintenance - such as £302 for an electric socket to be fitted, £47 for a key, and almost £500 to fit a lock" and arrangements that were "expensive and inflexible"21.

New Zealanders have their own experience of course. The above examples of failures of privatised companies to meet reasonable service objectives, let alone act in the public interest - and in some cases even to be financially sustainable - contrast with the acknowledged success of public enterprises such as Airways Corporation, Kordia, the Meteorological Service, Kiwibank and New Zealand Post (before it began to be run down in the face of falling mail volumes), even if some of them should not have been commercialised as SOEs.

Fabled "Mum And Dad" Investors

A further argument advanced under the Key Government was that partial privatisation of profitable State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) which they called euphemistically the "mixed ownership model", was in the interests of deepening the weak capital markets in Aotearoa and providing safe investment opportunities, purportedly for the fabled "mum and dad" investor.

The companies were Genesis Energy, Mercury Energy, Meridian Energy and Air New Zealand (which already had some private shareholdings). The sale of shares, leaving the Crown with a 51% shareholding, was completed in 2014. It came at a transaction cost of $140 million including $20 million lost by allowing some purchasers to delay payment.22 The New Zealand Council of Trade Unions (CTU), comparing the returns from the sale with the book value of the companies' assets, calculated there was a $383 million loss on sale23.

In fact, the Aotearoa listed share market remains shallow with these semi-privatised companies near the top of the capitalisation tables. While many small shareholdings remain with the four companies, their holdings are heavily outnumbered by large shareholdings, even excluding the Crown, many of which are owned overseas. As of 2023, shareholders with 5,000 or fewer shares made up between 65% and 87% of the shareholders, but they owned only 1% to 7% of the shares, while those with over 100,000 shares were between 0.15% and 2.5% of the shareholders but owned between 81% and 89% of the shares including the Crown's 51%24.

As we predicted at the time, the shares ended up in the hands of large, often overseas, investors. This repeats the experience of the 1990s with local electricity network companies whose shares were initially distributed to those who happened at the time to be customers. Indeed, many international trade and investment agreements prevent the Government taking action to stop this. But the partial privatisation experience is in any case highly problematic.

The Aotearoa government has had to continue to support Air New Zealand as if it were a wholly owned asset, as was shown in large subsidies and loans to the company during the covid-19 pandemic, without which Aotearoa would have been without air links to the rest of the world for a considerable period and the airline may not have survived.

In the case of the electricity generators and retailers, Meridian, Genesis and Mighty River, their "principal objective" by law as SOEs prior to partial sale was "to operate as a successful business"25. This already made them act in many ways like their private sector competitors, Contact Energy and TrustPower. Placing publicly owned services into the SOE form commercialised them as a first step on the way to privatisation.

Although the definition includes a responsibility to be "a good employer; and an organisation that exhibits a sense of social responsibility by having regard to the interests of the community in which it operates and by endeavouring to accommodate or encourage these when able to do so" the commercial imperatives in practice are primary, particularly in a competitive environment.

Not Solely To Make Money

This raises a key issue. Public ownership of functional assets is not solely to make money for the government. It is not like putting money in an investment fund. The ownership is valuable because the assets and the organisations are useful in the public interest. Their use-value produces a return in public benefits which are at least as important as - and often more than - their financial return. An electricity system that operates in the public interest must balance wider needs such as security of supply, environmental impacts, and low cost. Public ownership could be used to restore some of that balance if SOE profits were allowed to be compromised.

But as soon as a private shareholding is introduced, there is an expectation that they should produce dividends that are as high as competing investments. The flexibility in objectives that full public ownership provides disappears. They are fixated permanently on the pure profit-maximising objective of running as a successful business, the only public benefit (not insignificant) being that some of the profits return to the public purse.

The electricity system will continue to malfunction from a public interest viewpoint and the pressure will build for the partially privatised companies to be fully privatised. Even using them to deepen financial markets is a once-only short-term expediency which has proved ineffective - and at the same time a tribute to their success compared to much of the private sector which has either failed or been sold to overseas interests. But it is a misuse of essential public infrastructure.

"Economic Benefit" To Owners, Not Country

For those interested only in the financial returns, the share sale in the companies was hailed as a success because it greatly increased the flow of dividends to the owners. For example, Devon Funds Management Ltd, formerly Goldman Sachs JBWere NZ Limited, wrote in 2019:

"The total amount realised by the Government through selling shares in these three State-owned enterprises was $4.2bn. The current value for their remaining shareholdings today sits at a massive $11.4bn. The residual 51% stake that the Government has in Meridian Energy alone is worth $6.3bn (50% more than was received for the total sum received through the partial IPO [initial public offering] process!)".

"In 2013, these same entities paid the Government $140m in dividends. This year, the dividends which are forecast to be received by the Government from their stakes in Mercury, Meridian and Genesis are $466m, a total increase of 232% in the ~6-years since listing. The economic benefit that has been accrued during this new regime of ownership and management has been definitive".

The "economic benefit" they refer to is to the owners rather than the country as a whole. In an analysis in 202226, the CTU, 350 Aotearoa and FIRST Union found that the three partially privatised electricity companies plus Contact Energy (fully privatised in 1999) had distributed $8.7 billion in dividends between 2014 and 2021 from only $5.35 billion in profits (echoing the excessive Telecom payouts two decades earlier), and at the same time there was "systemic underinvestment" in generating capacity.

In particular there was underinvestment in renewable generation - which allowed "high-cost high-emission fossil fuel electricity to set the prices for cheaper renewable electricity, dragging prices up across the market and bolstering profits." An update the following year27 found the pattern of excess dividends over profits continued, and though investment had risen in 2021 to 2023, "in the last decade, total generating capacity has increased by only 1%". The surge in dividends and collapse in investment had occurred over the period during and since the partial privatisations.

Devon Funds did not disagree with the facts presented in these reports, but explained that the excess dividend payouts appeared less alarming if provisions for depreciation were taken into account: the companies were paying out their "free cash", in part built up to provide for depreciation.28 The reality was that the companies had set their charges to electricity users on the basis that provision had to be made for depreciation - and had then paid that provision out to shareholders.

Depleting their depreciation reserves is hard to square with Devon Funds' claim that the huge profitability of the companies was a "definitive" economic benefit, and even that was not a full explanation of the enormous dividend payouts. Their plentiful cash was a result of the companies exploiting their dominant position in the electricity generation and retail market. The book value of the companies had been regularly boosted by upward revaluations of their assets, reflecting their profitability - and in turn used to justify high profits as a rate of return on their apparently increasing assets.

Like the privatisation of Telecom, this "partial privatisation" has been exploited by the companies to extract maximum financial benefit for shareholders at the expense of everyone who depends on the companies' services. For electricity, this is every family and every firm. The result can be seen in continuing pain for households, unnecessarily slow progress in phasing out carbon-intensive generation, and closures of major wood processors such as Winstone Pulp's Karioi pulp mill and Tangiwai sawmill, and Oji Fibre's Kinleith and Penrose mills, losing hundreds of jobs. The financial gain for shareholders is at the country's wider economic cost.

The Politics Of Privatisation

It is easy to see from the above why that pioneering advocate of privatisation and PPPs, Savas, described privatisation as "more a political than an economic act"29. Indeed, the history of privatisation in Aotearoa is very much a political one. Treasury during the 1980s and 1990s had a much more radical view than simply privatisation: "a greatly reduced role for the Government, anticipating its eventual reduction to the administration of regulations and the funding of outputs" according to accountancy academics Sue Newberry and June Pallot, quoting State Services Commission and Treasury documents of the 1980s30.

This led to, as they described it, the embedding of rules into the public finance system that privilege outsourcing and privatisation. For example, the practice introduced during that period of Government agencies negotiating fully costed "outputs" to be "purchased" by their responsible Minister is a concept designed to make it convenient for those "outputs" to be provided on a commercial basis from outside the public service.

Newberry and Pallot point out that the full costing of "outputs” biases comparisons in favour of private providers, because it includes full overheads. In competitive tendering a private provider may well not include full overheads. In economic theory, prices tend towards marginal costs in a competitive environment; in practice prices may, in fact, be below cost if a bidder uses an uncommercial bid to burn off competitors and establish a position to raise prices on later occasions.

Driven To Seemingly Inevitable Conclusion

There is a sequence which can be seen in both central and local government which in the end drives the authorities and a reluctant public towards a seemingly inevitable conclusion of privatisation. The crucial distinction it makes use of is to stop the public viewing ownership of the assets as valuable because of their use value, and instead focus on their financial value. A financial asset's only use is to make money for the Government and leads to questions such as "why should the Government invest in this?"" or "why should the Government have such an unbalanced portfolio of investments?" which induce the public to forget its fundamental value - its usefulness as a public service.

The sequence may begin with commercialisation - like the SOEs in central government, and Local Authority Trading Enterprises (LATEs) in local government - requiring Government services to make a profit and act like commercial enterprises. The operation is seen by its users and others who benefit from it to be no longer working primarily in the public interest, losing support for its public ownership.

At the same time, it becomes a financial asset on the Government's balance sheet rather than one of its services. Then if part of its shareholding is sold off, the financial and commercial nature is reinforced. As it becomes increasingly profit-focused to serve the interests of its private investors, the public support for it wanes further. Finally, it is sold off, often at a time of real or exaggerated fiscal crisis.

What Newberry and Pallot described is another sequence starting with increased commercial outsourcing of services. It was reinforced by constant pressure on Government agency funding along with inconsistencies and gaps in financial controls which encourage and privilege outsourcing. For example, there were numerous controls on public service staffing levels, but few such controls on their replacement with contractors or consultants - a low-level privatisation trend that was evident during the 1990s.

The widespread use of expensive contractors is a feature even National-led governments have come to regret, but they find it hard to eliminate them in practice because of the depletion of the skills available in the public service, and the silos in Government that make the skills that exist in one agency difficult to access by others.

Current Government Likely To Expand PPPs

The use of PPPs is likely to be expanded by the current Government. Rules for PPPs have changed over the years. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, PPPs were not regarded as equivalent to debt, despite them committing the Government to a stream of payments in the same way as debt. That favoured PPPs because using them allowed the Government to keep within debt targets despite its liabilities increasing. That changed, so that by 2009, a PPP requiring the Government to make service payments over the life of the contract was treated as equivalent to debt although an actual Parliamentary appropriation was not required until the contract is signed.31

There were other changes under the 2017-23 Labour-led Government. It did not allow new PPPs in the education, health or corrections sector. That has been reversed by the National/ACT/New Zealand First Government. Some of the factors which previously biased cost-benefit analyses towards private provision were modified or dropped. For example, a 20% "deadweight loss" loading for public expenditure to reflect "the net cost to society attributable to ... the imposition of a tax or regulation" was previously required but has not been since 2016 according to Treasury cost-benefit instructions32 though it is not clear how this applies to PPPs.

Despite the lower cost of Government finance, departments were previously instructed to use the bidder's cost of capital to calculate the "public sector comparator" in deciding whether a private sector bid is lower or higher cost. This was used as the "discount rate" in the cost-benefit calculation - and as Treasury states, "small changes in the discount rate can have a significant impact on the total value of the public sector comparator". It appears that Treasury's standard discount rates are now used in many cases, though to the extent that they are higher than the interest rates at which the government is borrowing are still biased against public provision.

However, in 2024 the Infrastructure Commission brought back the biased use of the bidder's cost of capital expressly for "major projects" and PPPs. Financial expert and retired academic, Martin Lally, shows that "private sector entities undertaking these projects are far less efficient in raising capital than the Government, with a disadvantage in present value terms of about 32% of construction cost"34. For a $3 billion construction cost for PPPs - the value he estimates to date for school and roading PPPs - "this 32% disadvantage would amount to $960 million". Assuming that these PPPs were evaluated under these loaded rules, he writes:

"Unless there are PPP efficiencies elsewhere that could fully outweigh this 32% disadvantage, the PPPs adopted so far will have cost taxpayers up to $960m and to have done so whilst their adopters were led to believe through use of the Guidelines that they were instead superior".

PPP Roads

It would take very large "efficiencies elsewhere" to negate the $960 million financial disadvantage, efficiencies which have not been apparent in the Transmission Gully PPP. The other biased methodologies could be reintroduced by the Government elected in 2023, which wants to encourage the use of PPPs and other methods of private funding and provision.

These include tolls, congestion charges, higher vehicle registration fees and Road User Charges. There is a growing collection of advice, guidelines and rules around PPPs. The Infrastructure Commission provides standard form agreements and other advice35 and Treasury, the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) and the Office of the Auditor-General all weigh in.

This complexity mirrors the complexity of PPP contracts, which are costly both to set up and to run, and have been plagued with problems like those with prisons. There have been expensive time and cost over-runs and concerns about quality in the roading PPPs. In the 2024 Budget, Treasury recorded that Waka Kotahi had received a claim totalling $258 million from the Pūhoi to Warkworth motorway PPP, and was in a contractual dispute with the builder of the Transmission Gully PPP the size of which was unquantified.

The 18.5 km Pūhoi to Warkworth motorway north of Auckland was estimated to have cost $877.5 million to construct36 and is costing an average of $97 million a year in payments to the Northern Express Group. It will cost nearly $2.5 billion by the time the operation is handed back to the Government in 2048.37

Waka Kotahi will pay on average $129 million a year to the consortium that is operating the 27 km Transmission Gully motorway running north from Wellington: a total of $3.1 billion until 2047 when the operation is passed back to the Government.38 It has been plagued with delays (partly due to the pandemic) and disputes. When the road opened, Waka Kotahi said there was work still needed to complete it.

Radio New Zealand reported: "there are parts of Transmission Gully that when it opened it were already bumpy; the chip was already lifting on the road. Within two weeks they were already resealing parts of that road. If they had used more expensive materials, if they had used asphalt the whole way it would have been a far more high-quality road. Instead, where they could use cheaper materials, they did."39

Together the average yearly payment of $226 million on just 45.5 km of motorway run by the two PPPs will be equivalent to approximately one dollar in seven of what Waka Kotahi is allocated to spend on all State highway improvements in 2024/25, according to the final Government Policy Statement on Land Transport.40

The Impact On Māori

Since the rush of privatisations began in the 1980s, Māori have feared that the sale of State assets - particularly to overseas owners - would deprive them of the potential for compensation for the historical loss of their assets. Actions they have taken, both through the Waitangi Tribunal and politically have been major roadblocks in faster and more extensive privatisation. This surfaced again with the renationalisation of rail by the Clark Labour-led Government, and the "mixed-ownership" partial sale of electricity companies and Air New Zealand by the Key National-led Government (which Te Pati Māori was a part of, in practice enabling the sale to happen).

The history and concerns were well expressed by Dr Pita Sharples in a Parliamentary debate on the renationalisation of rail in 2008:41 "The Māori Party comes to this debate with a range of feelings about the Government's snap announcement to buy Toll's rail and ferry business for $665 million. The decision to claw back significant assets into the ownership of the Crown is a significant challenge to the context and the history of privatisation in Aotearoa. The major beneficiaries of privatisation - big business and transnational organisations - came into Aotearoa and bought up large on all our existing infrastructure".

"Too many New Zealanders have become casualties of that policy over the last decade or more. Māori have been hit particularly hard by much of this privatisation and sale of New Zealand assets through the sale of workplaces like forestry, the railroad, and Telecom, which employed huge numbers of Māori, and the break-up and sale of many of the country's freezing works. The Government was also selling off resources subject to Treaty claims - resources that were hard enough to recover when held by the Crown, but ones that would become nigh impossible to get back once ownership moved offshore".

"A Dark Period In Our History"

He recalled the opposition by Māori to the asset sales of the Lange/Douglas Government in the 1980s: "We think back to some 21 years ago, to 1987, when the Labour Government set about passing the State-Owned Enterprises Act, and we recall the advice of the Waitangi Tribunal at that time on this matter. The tribunal drew the nation's attention to the fact that the legislation took no account of the need to address Treaty of Waitangi concerns".

"On 29 June 1987 the full Court of Appeal unanimously declared that the proposed wholesale transfer of assets to State enterprises, without establishing any system to consider whether the transfer of such assets would be inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, would be unlawful. As a result, a clause was added stating that nothing in the Act would be inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty".

"This was a dark period in our history; a period that went against the interests of Treaty partners, and that ruthlessly and recklessly failed to take fully into account the consequences of the assets passing from the Crown upon the honour of the Treaty. Justice David Baragwanath, in referring to the historic New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General decision of 1987, demonstrated the glaring and profound damage that stripping the nation's assets would do in terms of the Treaty relationships: 'The Crown was about to deprive itself of the capacity to honour by return of disputed assets the manifold breaches of its Treaty obligations. They would pass into the hands of third parties and be irrecoverable'".

The Key Government intensely disliked the Treaty principles provision in section 9 of the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986 which again became a crucial issue for Māori in the controversy over "mixed ownership" partial asset sales, by which time Te Pati Māori was part of the Government.42 Because four of the companies being sold were large electricity generators, the dormant issue of ownership and control of water re-emerged.

A large hui convened by King Tuheitia called on the Government to halt the sale of electricity company shares until recognition of Māori ownership of water rights was settled.43 The Māori Council took a claim to the Waitangi Tribunal that Māori were being denied a future stake in the companies and in water and geothermal power. As the Tribunal was hearing the issue, the Government threatened to ignore it if it ruled Māori owned the water.

In the end, the Government replicated section 9 of the SOE Act in section 45Q of the new legislation for the "Mixed ownership model companies" in the Public Finance Act, but with a crucial addition: that it applied only to the Crown and not any other persons. Thus, the part-privatised companies themselves were arguably not subject to Treaty principles, and neither were new owners if they were ever fully privatised. Māori succeeded in delaying the partial asset sales, but not in stopping them. However, the battle made it clear that a full sale would of the power companies would buy a further fight.

Who Benefits?

Given the conflicts with the public interest, and the high financial risks involved, it is worth reflecting on who benefits from privatisation.44 There are well known lobbies such as the New Zealand Initiative which advocate for privatisation as a matter of principle - a principle which is hardly surprising given the membership of the organisation.

However, in the present circumstances it is useful to look at PPPs in particular. Castalia describes a PPP contractor as typically being "a private consortium of financiers, construction companies and facilities management firms". In addition, PPPs have very high transaction costs with contracts which are highly complex documents and costly to draw up. This is to the considerable benefit of lawyers, accountants and other professionals.

The full transaction cost estimate for school PPPs in Aotearoa was suppressed from Castalia's documents, but for the first school, the public sector cost alone "will be as high as $6 million", and for Australia they suggest it is a long run cost of $8.7 million per school, $4.7 million of which is public sector costs. These are very significant overheads when the estimated cost of even a large (2,200 pupil) school was only $55 million.

Lobby Groups

The most active lobby for PPPs in Aotearoa is Infrastructure New Zealand, formerly the New Zealand Council for Infrastructure Development, founded in 2004 by a number of companies. At inauguration it was headed by former National Party leader Jim McLay, by then chair of Macquarie New Zealand, one of the biggest infrastructure owners in the world with a well-established interest in taking over public assets and services.

The group is an advocate for greater spending on infrastructure, including "appropriate use of public and private sector debt as a means to finance infrastructure investment opportunities", and is working "to refine the PPP model and developing a model to bundle smaller ($25m-100m) infrastructure projects for private investment".45 The Council was formed to promote public-private partnerships46.

While including some central Government agencies, local governments and entities owned by them, as well as the Australian High Commission and the UK Department for International Trade, the great majority are private including banks and other financiers, engineering firms, construction companies, major services corporations, accountancy and law firms which would be expected to benefit from the private sector taking over public services47.

Internationally there are powerful lobbies with similar memberships that influence not only the Governments of the economic superpowers, the US and the European Union, but also international agencies such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO). For example, the US Coalition of Service Industries and the European Services Forum represent the interests of the huge corporations in the services sector that makes up about 70% of the production of these two economies.

Both the groups and their individual members have been highly influential in setting the direction of trade and investment agreements with the objective of opening markets to them. In the services sector, opening markets most frequently means company takeover or provision of service contracts, which in the context of Government means privatisation in its many forms.

The groups played a crucial role in the establishment of the General Agreement on Trade in Services during the Uruguay Round which led to the formation of the WTO. Similar, and usually stronger, provisions are in the free trade agreements Aotearoa has signed over the last two decades. According to Harry Freeman of American Express in 2000: "The US private sector on trade in services is probably the most powerful trade lobby, not only in the United States but also in the world"48. Little has changed in that regard.

Impact Of Privatisation On Distribution Of Income & Wealth

Thomas Piketty in his book "Capital In The Twenty-First Century"* identifies privatisation, particularly since the 1970s, with what he calls the "conservative revolutions" and what we call neoliberalism, and as one of the sources of the sharp growth in private wealth and inequality he documents.49 * Reviewed by Greg Waite in Watchdog 146, December 2017. Ed.

The same is true in Aotearoa. While there were other more direct causes of the dramatic increase in income inequality in the 1980s and 1990s - particularly cuts in company and top personal tax rates, high unemployment, severe cuts in social security benefits, and the deregulation of industrial relations and deep cuts into union membership and collective bargaining through the Employment Contracts Act 1991 - privatisation also played a part. In part the suppression of wages and cuts in corporate and top personal tax rates was also intended to make privatised operations attractive to local and overseas buyers.

Redistribution Of Public Assets Into Private Hands

While Aotearoa data on wealth distribution is weak, particularly prior to the 2000s, the redistribution of public assets into private hands can be illustrated by the change in ownership of assets used in production. These include buildings, plant, machinery and equipment, and intangible assets but are only a piece of the map of wealth because they exclude land and financial assets (though productive assets are reflected in the value of shareholdings which are part of those financial assets). Given that ownership of land and financial assets are the main assets that distinguish the very wealthy, they are important gaps. On the other hand, the assets used in production are vital to the Aotearoa economy.

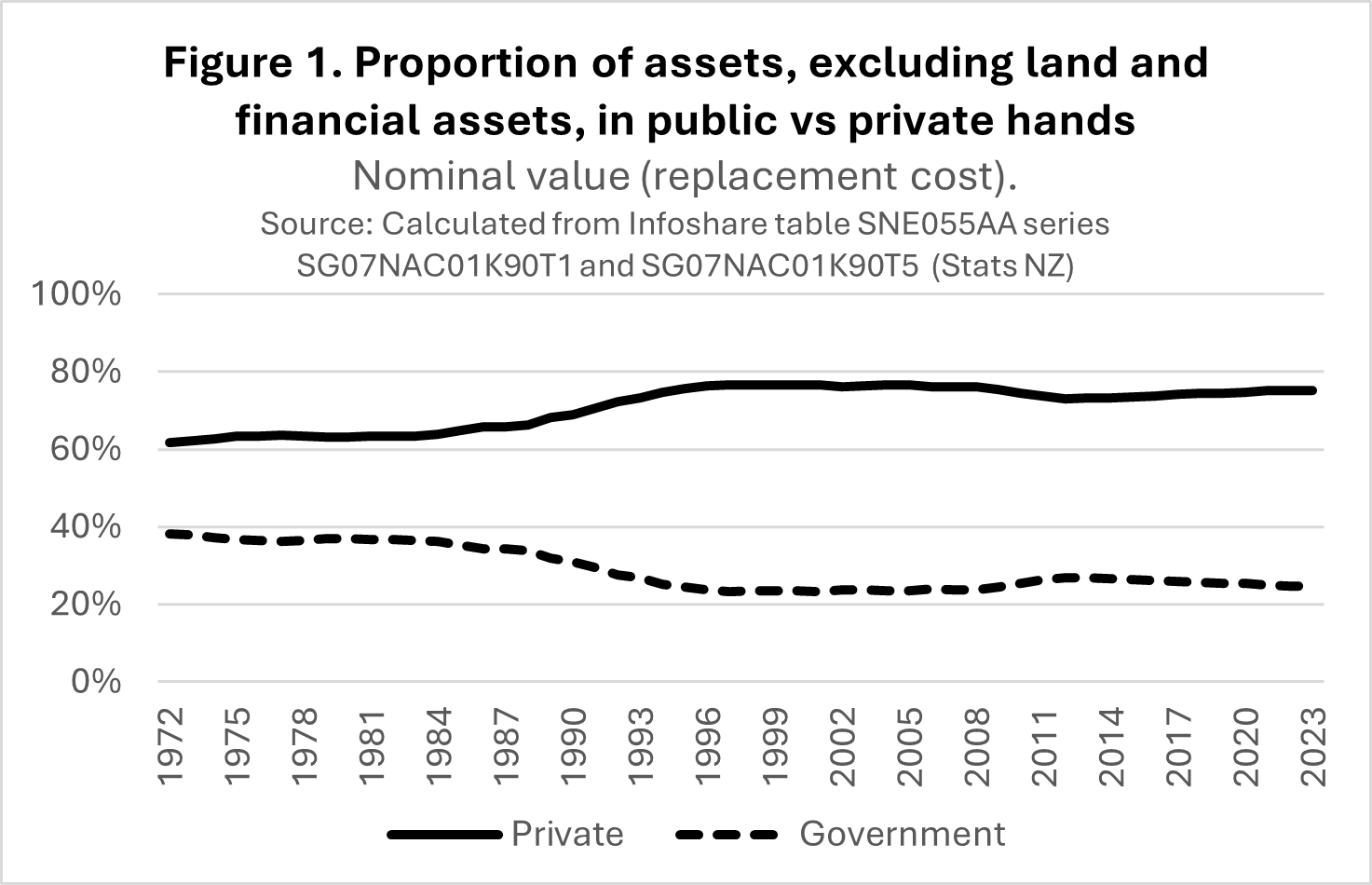

Figure 1 shows the proportions of these assets in public and private ownership. The sharp change in proportion of ownership that occurred between the mid 1980s and mid 1990s is very clear: between 1983 and 1997 the proportion of assets in private ownership increased from under two thirds (63.5%) to over three-quarters (76.7%).

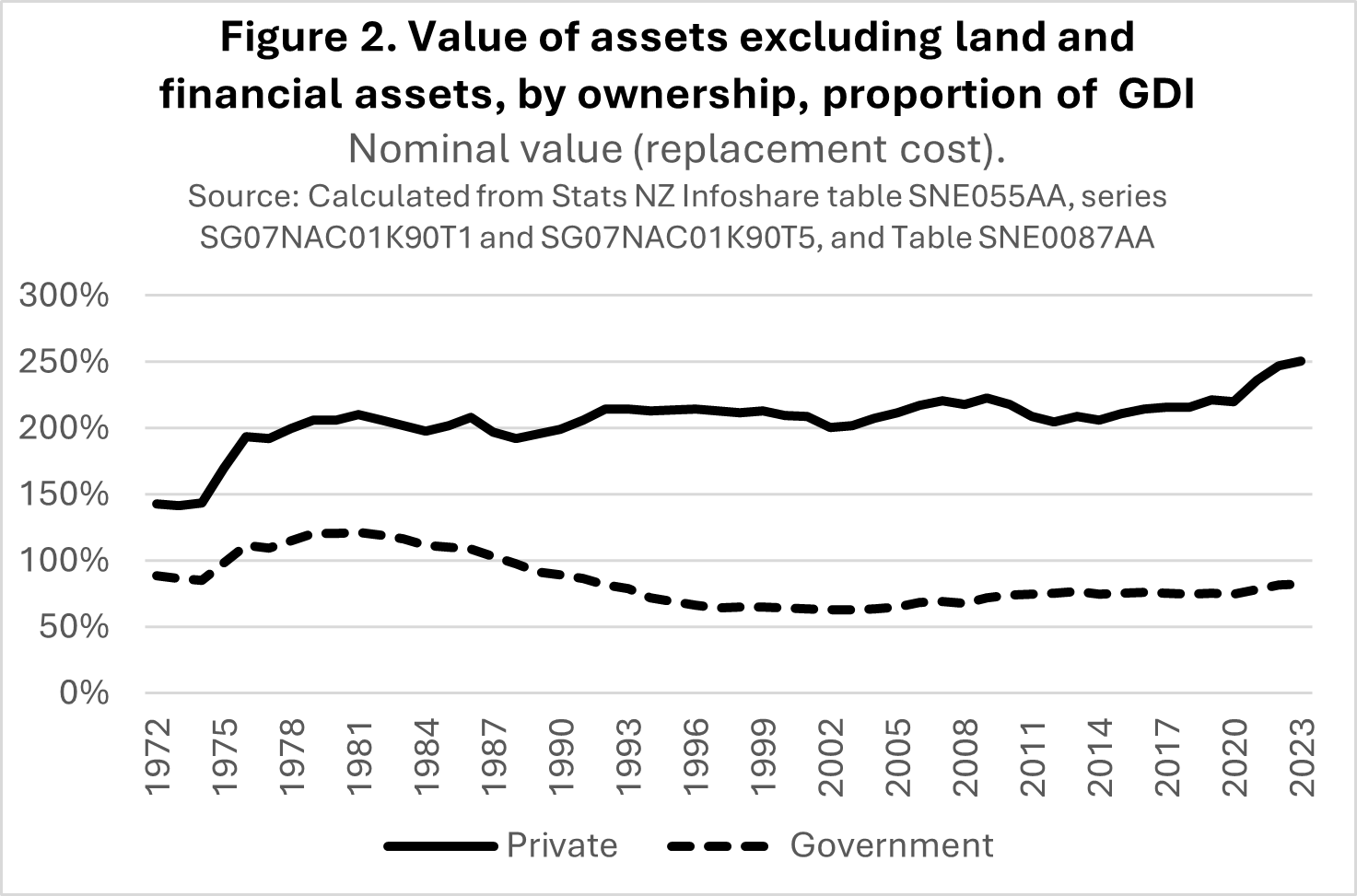

In fact, as Figure 2 shows, public ownership of these types of assets almost halved as a proportion of the total income of Aotearoa (Gross Domestic Income or GDI) from a peak of 120.5% in 1979 to a low of 62.8% in 2002 (though they resumed their increase in dollar value from 1995). Meanwhile private ownership held at around 200% of GDI throughout the period but rose to 250% between 2012 and 2023. The privatisations also reduced the share of the income of Aotearoa going to wage and salary workers, in favour of income paid to the owners of capital.

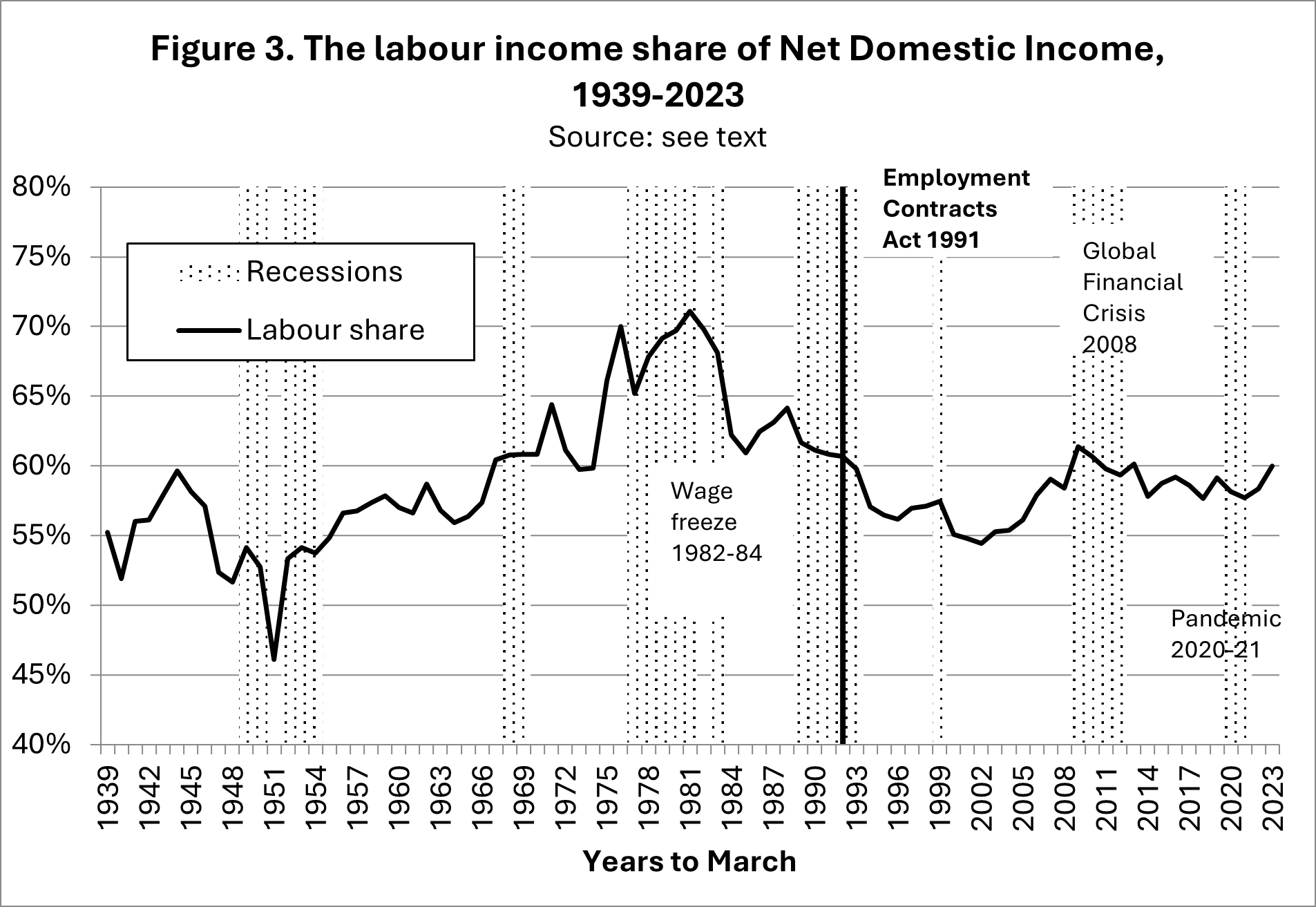

Figure 350 shows the share of Net Domestic Income of Aotearoa that wage and salary workers have received (the Labour Income Share) since 1939. It rose to a peak in 1981, fell steeply under a wage freeze imposed from 1982 to 1984 by the Muldoon Government and after a brief and minor recovery until 1988 began falling again. It did not begin a more sustained recovery until 2003, though that lasted only until 2009 since when it has fallen apart from an uptick in 2022 and 2023.

It fell steeply through the period of the deep policy-induced recession beginning in the late 1980s with unemployment reaching 11% in 1991-92, the enactment of the Employment Contracts Act 1991, the brutal benefit cuts in the same year, and the ongoing programme of commercialisation and privatisation of Government operations throughout the 1984 to 1999 period. (Note that years in the figures end in March, and so contain three quarters of the previous calendar year. For example, the 1992 year includes the coming into force of the Employment Contracts Act in May 1991 and the cuts to benefits announced in the July 1991 Budget.)

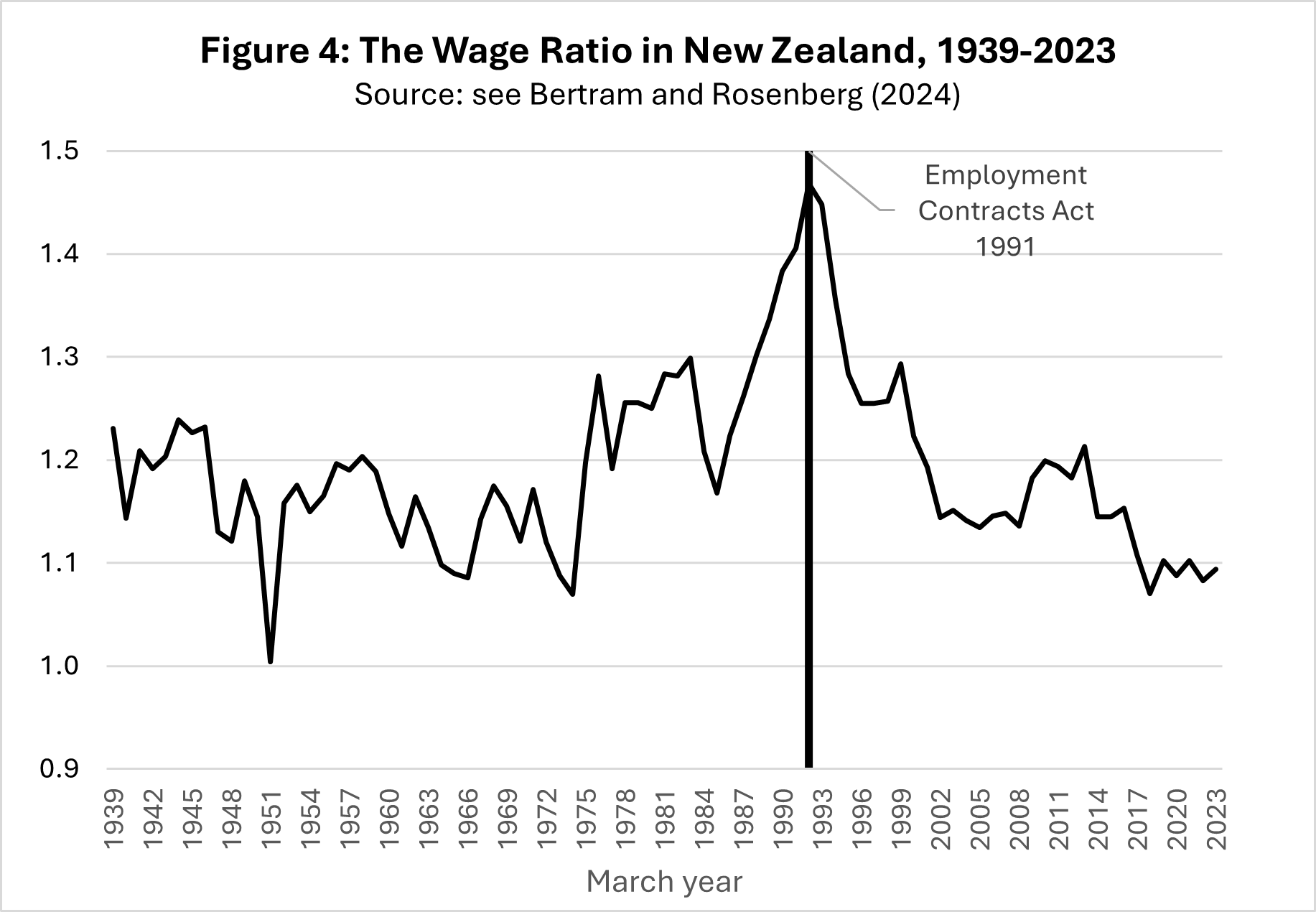

Given the intensity of events around 1991 that were suppressing wages, especially the Employment Contracts Act, it may appear odd that the period is barely distinguishable in the steep downward fall of the labour income share over the two decades from 1981. Geoff Bertram and I have shown that the reason is that the labour income share is affected not only by wage rates but by employment rates.51 If the labour income share is adjusted by the employment rate of wage and salary workers - the proportion of employed wage and salary workers in the adult population - the dramatic turnaround in the bargaining power of workers that occurred in the early 1990s becomes apparent.

We call the ratio of the labour income share to the employment rate the "Wage Ratio". It is also the ratio between the average annual income per wage earner and the average annual income per adult, where incomes are "market incomes" before taxes and any transfer payments such as social welfare benefits. A rise in the Wage Ratio indicates that the market earnings of wage and salary workers are increasing relative to other recipients of market incomes - mainly those receiving income from capital: dividends from shares, interest from other financial assets, house rents and self-employment. A fall means wage and salary earnings are falling behind.

Figure 4 shows the Wage Ratio from 1939 to 2023. It rose to a peak in 1992 and then collapsed. The peak was due to market incomes from capital falling in the deep recession at the time - not because real wages were increasing rapidly. There is a clear structural break at the time of the events of the early 1990s. Analysis points to this break being due to a change in the bargaining power of workers. Where previously workers could bargain for higher wages more successfully when employment was high, from the early 1990s that bargaining power disappeared. The Wage Ratio fell from 1992 onward.

Privatisation's Role In Fall Of Labour Income Share

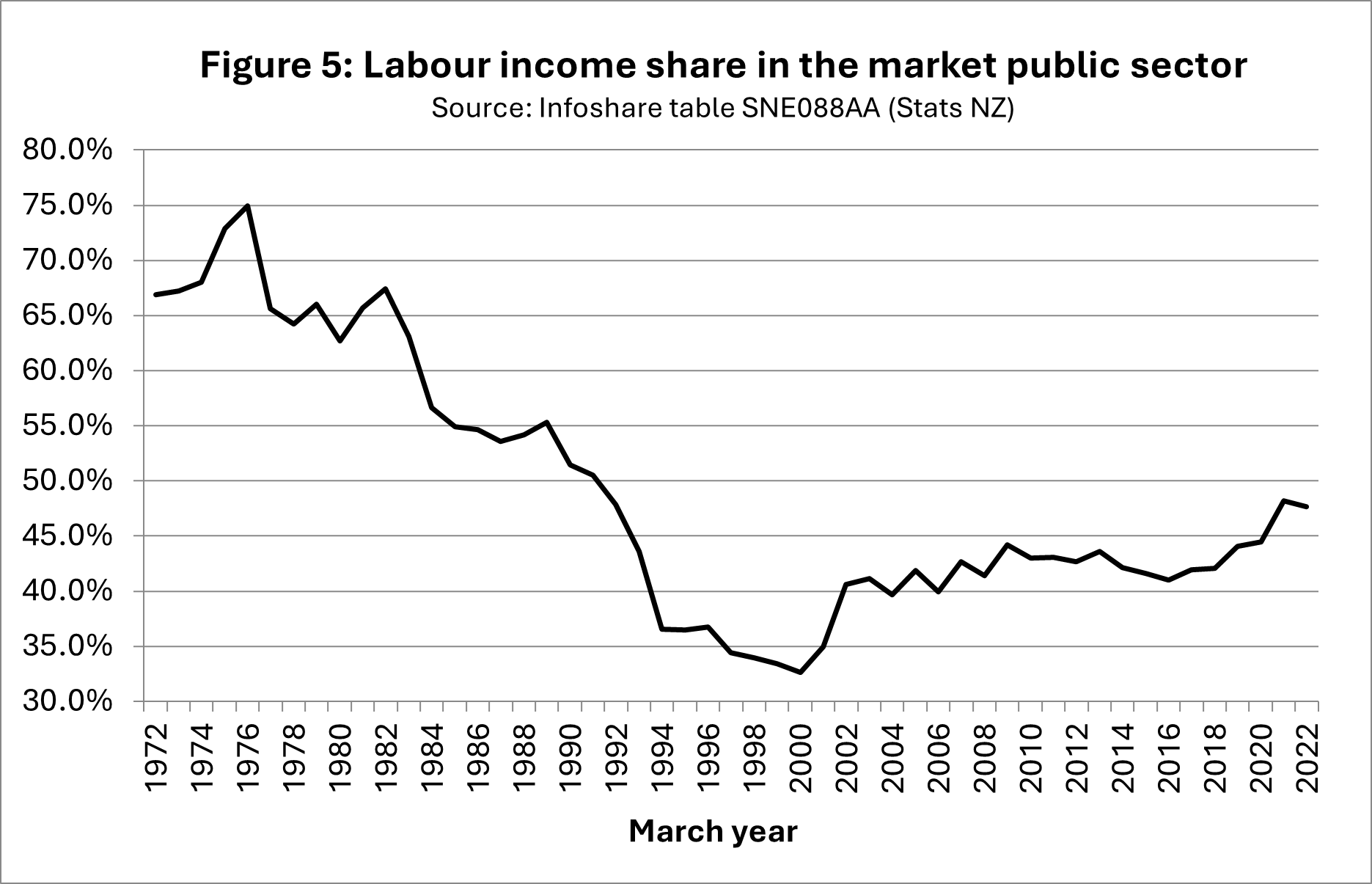

What part did privatisation play in the fall in the labour income share? Figure 5 shows the labour income share for the "market" public sector since 1972. This is the part of the public sector that acts in a commercial way, charging for its products or services and sometimes in competition with the private sector. Comparing it with the labour income share for the whole economy in Figure 3, it collapsed even more dramatically from 1982 until 2000.

Until 1982, the labour income share was similar to that for the non-market (not for profit) public sector, reflecting the fact that many public services which were later fully commercialised or privatised, functioned until then more as not-for-profit public services. Such public services have a very high labour income share because there is essentially no profit52. As these services were commercialised, usually as SOEs, and required to make a profit similar to private companies, wages and other working conditions were reduced along with large scale redundancies.

This severely cut their payrolls and greatly increased their profits, reducing the labour income share. Some operations were then sold to private buyers, moving into the private sector: the SOE model was designed to prepare the operation for privatisation. The labour income share in the market public sector halved from around 70% to 33% at its lowest point, a low share for any part of the private market sector, but particularly low given that these were often services and labour-intensive.

There is no doubt that this commercialisation and privatisation process contributed to the fall in the labour income share. Benjamin Bridgman and Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy go further and ascribe most of the fall in the labour income share in the whole economy to these processes. That is going too far: the labour income share was falling in the private sector at a very similar rate to the full economy, and it fell in most industries such as manufacturing, retail, accommodation and food services, many of which had no public ownership, so there was more going on than the hollowing out of the public sector.53

In addition to the direct effect of commercialisation and privatisation, suppressing wages and laying people off, the size of the upheaval would have had wider effects on wages and conditions. Bridgman and Greenaway-McGrevy estimate over 40,000 people were laid off. The layoffs mostly occurred at a time of high and rising unemployment. That would have depressed wages generally and encouraged other employers to claw back working conditions.

Foreign Investors Were A Beneficiary

Foreign investors were a beneficiary of the privatisation programme. Many Government assets were sold to overseas buyers, and in other cases local small shareholders gradually sold their shares, often to overseas purchasers. The Foreign Direct Investment Advisory Group set up in 1991 to report to the Prime Minister, estimated in 1997 that between 1986 and 1996, approximately 42% of foreign direct investment flows into Aotearoa were to purchase State assets.54

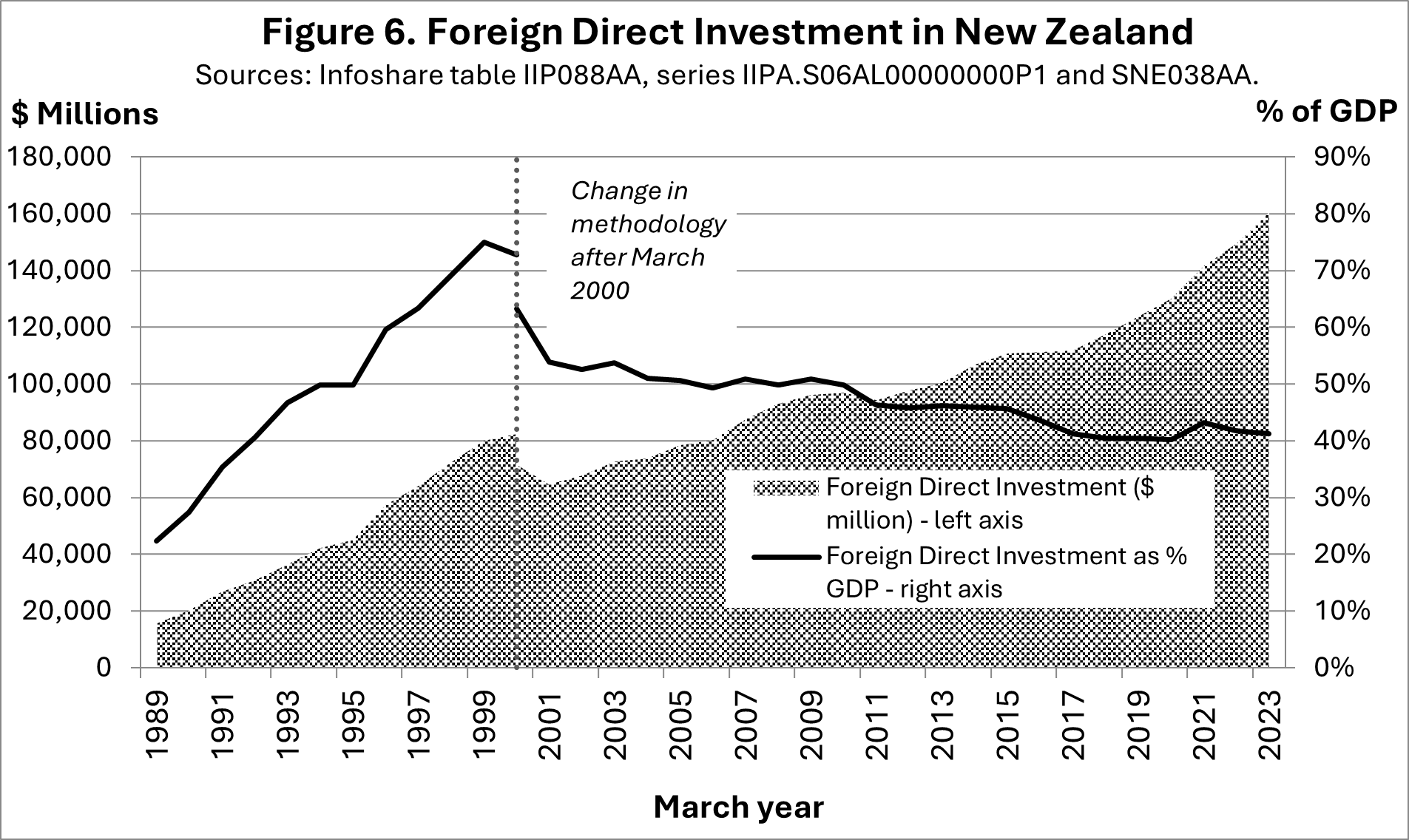

As Figure 6 shows, the stock of foreign direct investment (where the investors have a degree of control of a company) rose rapidly during the 1990s as a proportion of GDP (gross domestic product) but fell off from the 2000s onwards. The remittance overseas of the profits of overseas owned companies is a significant factor in the large current account deficit of Aotearoa.

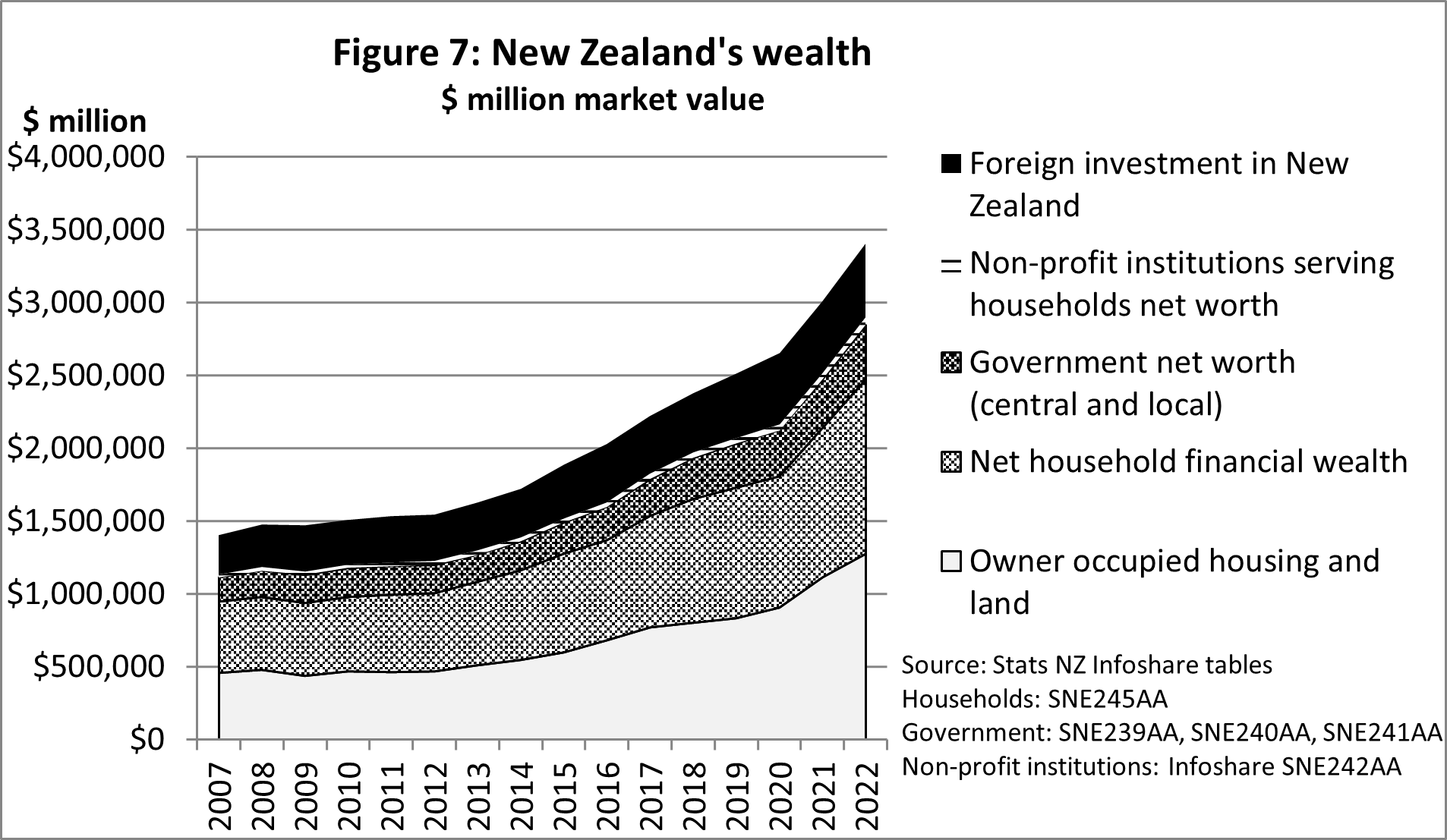

The current position is that, in total, overseas holdings of wealth in Aotearoa including debt owed overseas, but not limited to privatised assets, now exceeds the net wealth of the government, as shown in Figure 7. The figure shows the distribution of wealth between sectors of the economy including households, which are deemed to own the companies and debt which are not owned by either the Government or overseas investors. What it does not show is that the distribution of wealth within households is very unequal. In particular, as already noted, the ownership of financial assets including shares and bonds, is concentrated in the wealthiest households and it is they who are the main domestic beneficiaries of privatisation.

It was not unique to the many privatised operations that ended up in overseas ownership, but many of the operations had little competition and indeed often were in a monopoly or near-monopoly position. Examples were in telecommunications, electricity, airports and Air New Zealand, insurance and banking. The neoliberal enthusiasm for shrinking the State by privatisation exceeded its opposition to "business monopoly", and there was money to be made by the corporations funding the most powerful organisations advocating for the neoliberal programme.

An alternative to State ownership where competition is limited is effective regulation, yet that is in conflict with neoliberal views on the role and power of the State. At any rate, competition regulation in Aotearoa has proved weak and unable to effectively prevent dominant companies from making use of their position as we have seen in the electricity sector.

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on the privatisation of central Government assets, but similar processes have occurred in local government, where utilities such as airports, ports, public transport and waste disposal have in many cases been commercialised or fully or partially privatised, often contentiously. That process continues, with controversy in Auckland over the sale of remaining Auckland Airport shareholdings; in Wellington, again over the sale of its remaining shareholding in the city's airport (and the main domestic hub for air traffic in Aotearoa), and also over the private operators of its bus services.

Christchurch, a city which retained most of its assets during the 1990s, is again facing pressure to sell. In common to all of them is the clash between those who regard the assets as simply financial, which can be exchanged for cash to reduce rates (either for current costs or future investment), and those who see them as strategic whose value lies in the use that the region can put them to if it retains or regains that control.

The National/ACT/New Zealand First Government elected in 2023 has made clear its willingness to fund investment by any means available, including PPPs, user pays (such as water charges, congestion charging and tolls) and special purpose taxes. This is at the least a commercialisation process which has its own problems, but with PPPs there are the additional concerns about value for money, and the ability of the PPP consortium to use its monopoly control of the asset to ramp up costs in future.

There are elements within the ruling parties which would be interested in selling off troublesome assets such as KiwiRail or its ferries. Privatisation of social services, such as for early childhood education, elderly people and people with disabilities, is well advanced and highly problematic because it relies on ongoing public funding and often low-paid yet dedicated workers. Charter schools are being re-established.

While some user charges have benefits, such as reducing the use of cars and the production of carbon emissions, in the case of congestion charges and higher road user charges, fuel taxes and car registration fees, they may also discourage use of electric vehicles which are important in reducing emissions and can have excessive impacts on low-income drivers who have no choice but to drive and use costly routes. The provision of alternative transport options such as untolled routes and public transport, and free water allowances for households, are essential to the design of such developments.

There is constant pressure from business groups to increase their profit-making opportunities in taking over services from Government. While it is of course normal for businesses to lobby in their own interests, we need to be cautious in accepting the advice of an organisation such as Infrastructure New Zealand or its international counterparts. We should be equally wary of the expertise offered by their membership and other commercial entities with similar vested interests. They cannot be assumed to be objective judges of the merits of privatisation.

This just underlines what is already in bold and italics: as Savas stated, privatisation is more a political than an economic act. It is also of course a commercial act. But we have seen that little can be taken at face value. Apparently objective comparisons can be loaded with political intent. Theoretical advantages have little empirical support (and indeed should lead to questions about the strength of the theory). Objectives change to fit the available factoids, and commercial interest is disguised as expertise.

Re-Equip State To Govern In Public Interest

Amidst all of this, the importance of the public interest, which is not simply about financial considerations, is lost. We have a highly deregulated society and economy as a result of the programme of extreme neoliberalism from 1984 to 1999. Substantial parts of the programme remain in place, as we have seen. We have all too few levers remaining to manage our economy, environment and society in the public interest.

The most powerful commercial forces have been strengthened and the countervailing power of Government weakened or co-opted. Public services, assets and enterprises provide some of the levers we need. We should exercise great caution before taking any further steps toward private power, and indeed should be contemplating the reverse: reequipping the State to govern in the public interest.

Footnotes:

- The Mont Pelerin Society and The Mont Pelerin Society - Statement of Aims

- The Washington Consensus as Policy Prescription for Development", John Williamson, 31/1/04. World Bank.

- "Testing Years Ahead For Telecom", by Brian Gaynor, New Zealand Herald, 26/5/01.

- "Telecom: What A Winner!", financial report on winner of the 2004 Roger Award, Sue Newberry.

- "Investment: Track Record Costly To Public", by Brian Gaynor, New Zealand Herald, 21/10/00

- "A Tough Case ... And A Long One", by Brian Gaynor, New Zealand Herald, 16 /10/04.

- "Government Toll Buy A Sad Indictment", by Brian Gaynor, New Zealand Herald, 10/5/08.

- For example, "Improving Infrastructure Funding And Financing", by Chris Bishop, Minister for Infrastructure.

- http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/spa/facultystaff/facultydirectory/bio_savas.php, accessed 3/10/10

- "Privatization And Public-Private Partnerships", Chatham House, New York, NY, p.3.

- "Privatisation: 'More A Political Than An Economic Act'", by Sue Newberry, presentation to "Privatisation By Stealth" conference, 16/3/08.

- http://www.castalia-advisors.com/about_us.php, accessed 21/9/10

- "NZ's First PPP Prison To Be Built At Wiri", Bill English, Judith Collins, 14/4/10, accessed 24/6/24.

- "Private Prison To Cost $300m To Build, $60m A Year To Operate", by Martin Kay, Dominion Post, 13/7/10, p.A9

- "School PPPs In New Zealand: Will PPPs Provide Value for Money As A Method Of Procuring Schools In New Zealand? Stage One Business Case", Castalia Strategic Advisor, May 2010, p.24, produced for the New Zealand Government, released to NZEI under the Official Information Act

- "Privatising Justice: The Impact Of The Private Finance Initiative in the Criminal Justice System", Centre for Public Services , p.26, accessed 4/10/10.

- "School PPPs In New Zealand: Will PPPs Provide Value For Money As A Method Of Procuring Schools In New Zealand? Working Paper No. 2, Cost Benefit Analysis", Castalia op. cit., p.25.

- "Reframing Privatisation: Deconstructing The Myth Of Efficiency", Steve R Letza, Clive Smallman and Xiuping Sun, Policy Sciences, Vol. 37, pp. 159-183, 2004, p.168.

- "The Cost Of Using Private Finance For Roads In Spain And The UK", Jose Basilio Acerete (University of Zaragoza), Jean Shaoul, Anne Stafford and Pam Stapleton (University of Manchester), Australian Journal Of Public Administration, Special Issue: Public-Private Partnerships, Volume 69, pages S48-S60, March 2010.

- "The Great PFI Swindle", Sunday Herald, Glasgow, 17/5/08.

- "IoS Special Investigation: How Government Squanders Billions: Jonathan Owen And Brian Brady Reveal The Staggering Cost Of PFIs - Some £300bn - In The Third And Final Part Of Our Investigation Into Whitehall Waste", The Independent on Sunday, 24/1/10, p. 30-31.

- "Government Share Offers: Final Costs Release", Treasury, 20/6/14, and Table 2.11, p.40 of the Budget Economic and Fiscal Update 2014.

- "Selling Off Our Assets", NZCTU, 2014.

- From the four companies' 2023 annual reports.

- State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986, s.4.

- "Generating Scarcity: How The Gentailers Hike Electricity Prices And Halt Decarbonisation", New Zealand Council of Trade Unions Te Kauae Kaimahi, 350 Aotearoa, & FIRST Union, November 2022.

- "Generating Scarcity: 2023 Update", 350 Aotearoa, New Zealand Council of Trade Unions Te Kauae Kaimahi, FIRST Union.

- "The Other Side Of The Journey", Greg Smith, Devon Funds, no date.

- Quoted by Newberry, op. cit.

- "Fiscal (Ir)responsibility: Privileging PPPs In New Zealand", Susan Newberry and June Pallot, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, 2003, pp. 467-492.

- "Guidance For Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) In New Zealand", Prepared by the National Infrastructure Unit of the Treasury, October 2009, Version 1.1, p.14.

- Te Tai Ōhanga/The Treasury - CBAx Tool User Guidance

- Te Tai Ōhanga/The Treasury - Discount Rates and CPI Assumptions for Accounting Valuation Purposes.

- "Public-Private Partnerships And The New Zealand Guidelines", Martin Lally, 20/6/24.

- NZ Infrastructure Commission/Te Waihanga - Guidance and documentation of PPPs.

- NZTA/Waka Kotahi: Ara Tūhono - Pūhoi to Warkworth

- "Two Highway PPPs Cost $226m A Year", Oliver Lewis, BusinessDesk, 2/5/24.

- Lewis, op cit.

- "Public Private Partnerships And Big Infrastructure Projects", Sharon Brettkelly, 9/8/23, Radio New Zealand.

- Calculated from Table 5, "Activity Class Funding Ranges", taking a mid-point in the range for State Highway Improvements. The Government Policy Statement is available here.

- Urgent Debate On Toll Holdings - The Return Of Trains And Ferries To Crown Ownership, Pita Sharples, Co-leader of Te Pati Māori, 13/5/08 (Parliamentary debate). New Zealand Parliament, Wellington, Aotearoa.

- "Key's Attitude 'Corrosive' - Māori Party". Kate Chapman, 13/7/12, Dominion Post, p. A2.

- "Māori Speak As One On Water Rights". Tracy Watkins, 14/9/12, Dominion Post, p. A1. Available at

- For more details see "International Pressures To Privatise", Bill Rosenberg, 16/3/08.

- Infrastructure NZ

- "No Need For 'Master Plan'", by James Weir, Press, 20/7/04.

- Infrastructure NZ - Find A Member

- Brookings-Wharton Papers On Financial Services 2000, 453-463, accessed 29/6/24 24.

- "Capital In The Twenty-First Century", Thomas Piketty, Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014, e.g. p.183-187.

- An update of Figure 3 in Rosenberg, B. (2017). "A Brief History Of Labour's Share Of Income In New Zealand 1939-2016". Bill Rosenberg. In G Anderson (Ed.), "Transforming Workplace Relations", Victoria University Press.

- "The Employment Contracts Act 1991 And The Labour Share Of Income In New Zealand: An Analysis Of Labour Market Trends 1939-2023." Geoff Bertram, Bill Rosenberg, New Zealand Economic Papers, pp1-27.

- The only "profit" recorded in the National Accounts for non-market services is the depreciation on their assets.

- "The Fall (And Rise) Of Labour Share In New Zealand". Benjamin Bridgman and Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy. New Zealand Economic Papers, 24 August 2016, pp1-22.

- "Inbound Investment: Facts And Figures", Foreign Direct Investment Advisory Group. August 1997, p.6.

Watchdog - 169 August 2025

Non-Members:It takes a lot

of work to compile and write the material presented on these pages - if

you value the information, please send a donation to the address below to

help us continue the work.

Foreign Control Watchdog, P O Box 2258, Christchurch, New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Email