REVIVING STRANDED ASSETS IN THE NZ GAS SECTOR

- Ed Miller

Review

On 1 October, 2025, Energy Minister Simon Watts released the long-awaited Frontier Economics review into the NZ electricity market, along with the Government's proposed policy responses. The announcement was a fossil fizzer, but it could have been much worse. The main announcements were a Government commitment to help finance new firming (i.e. thermal) infrastructure where there is a clear commercial case to do so, and confirmation that the Government was still considering (but had not yet actually committed to) launching a procurement process for a new liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal to import gas and back up the system.

Key proposals didn't survive Cabinet, such as Frontier's top recommendation of selling the Government's gentailer shareholdings and using the proceeds to acquire or contract all thermal capacity in the market. Government control of thermal capacity - which tend to set the price or cheaper renewable generation - may have merits (particularly if operated with the objective of maintaining lowest cost energy security), but not at the cost of the Government's existing shareholding.

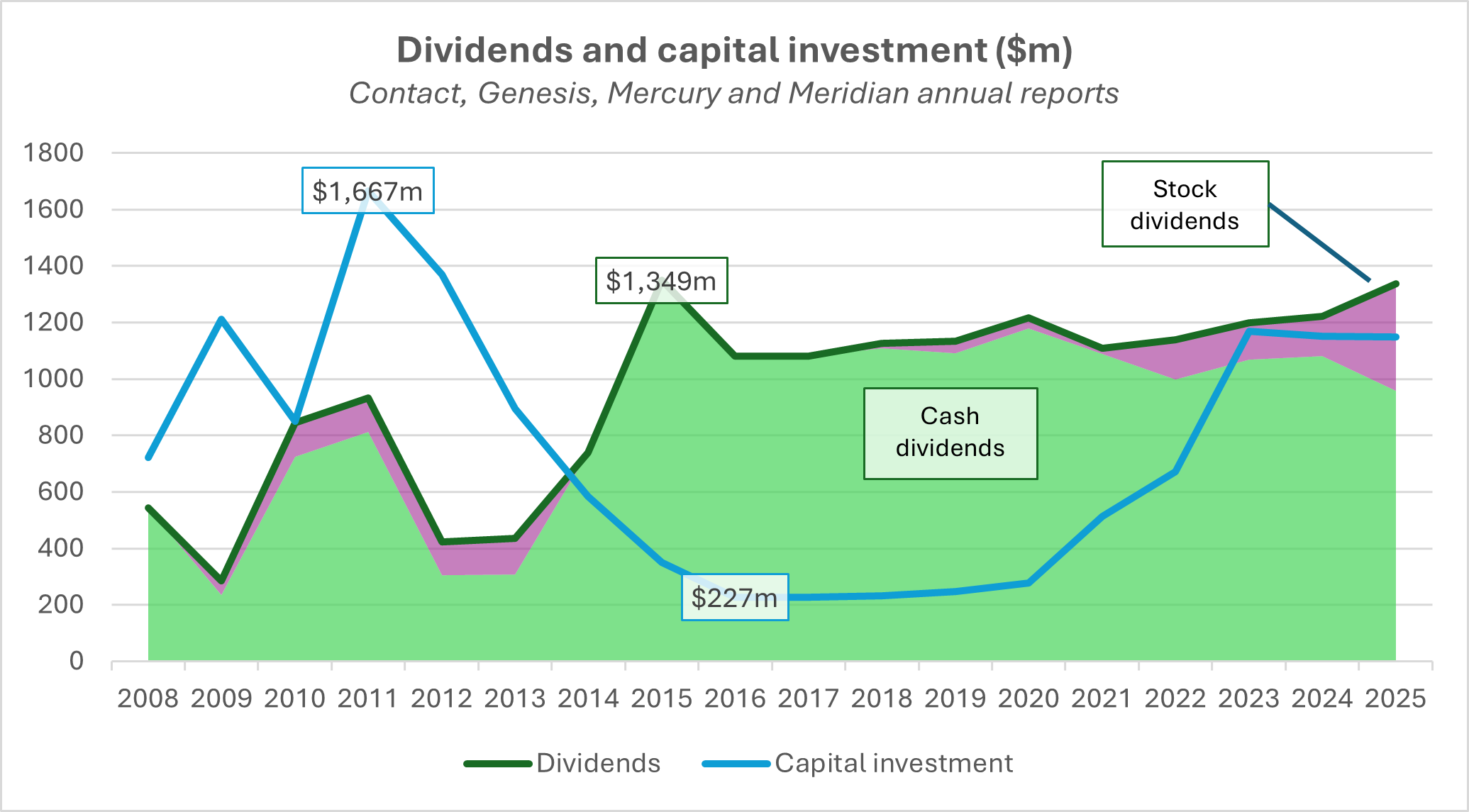

It was however telling that New Zealand First had released a report two weeks prior that included a range of more explicitly radical proposals, including the structural separation of the gentailers into their generation and retail functions, and as a last resort, renationalisation. In recent years numerous studies (some of them penned by myself), have identified a collapse in gentailer capital investment in the wake of partial privatisation in 2013, coupled with an enormous rise in dividends for shareholders.

Gentailers themselves pointed to uncertainty about whether NZ's largest electricity consumer - the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter - would continue to operate, but passed on the benefits to shareholders rather than consumers. Together the gentailers spent less than a quarter of a billion a year from 2016 to 2020, while delivering more than a billion a year in shareholder dividends.

Offshore Oil And Gas Ban

During this period (in 2018) the Labour-led government passed the offshore oil and gas ban. New Zealand First voted for it, as did the Greens. Gas production in NZ had been declining since the peak of gas field Pohokura in 2014, and the departure of transnational companies like Statoil and Anadarko had helped contribute to an emerging consensus that there were no economically recoverable reserves in NZ.

I believe it was a mistake for the Ardern government to implement the offshore ban without an accompanying energy strategy that required investment in generation and storage capacity. While energy projects typically take years to build, the Government should have used its majority shareholding in the three largest electricity companies in the country to accelerate their build programmes and expand their generation and storage portfolios. Only when security of energy supply could be guaranteed should the ban have been implemented.

Rising wholesale electricity prices and a slew of factory closures in recent years have seen these decisions come under increased scrutiny. The Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment has reported that as of 1 January 2025 natural gas "have reduced 27% compared to last year", following an equally significant reduction in "proven plus probable" reserves in the previous years. The coalition Government has gone hard on identifying the offshore gas ban as the root of the problem, and Labour's failure to at least encourage gentailer investment during the Ardern government has meant they cannot effectively fire back with a critique of the logic of privatisation.

At the same time, there is certainly more that could be done. Canadian-owned methanol exporter Methanex alone has gas contracts equal to almost half of NZ's production, granting the company substantial market power. It is one of the largest recipients of carbon credits in the country and transfers substantial income out of the country, both through dividends and related party loans that could have the effect of reducing its taxable income in New Zealand.

Re-allocating those rights before their expiry in 2029 would substantially increase gas availability in the country in the coming years. This would increase short- and perhaps medium-term energy, but they are unlikely to impact long-term security, as any offshore discoveries are likely of an order of scale less than historical finds. Any additional time afforded through the reallocation of Methanex's rights should be used to accelerate renewable generating and storage capacity.

Enter Brookfield

The weekend after the Minister of Energy reannounced the LNG terminal, the Australian Financial Review (5/10/25) reported that trillion-dollar Canadian asset manager Brookfield Asset Management was within days away from finalising terms to acquire Kiwi gas and electricity distribution infrastructure owner Clarus Group from Igneo Infrastructure.

The deal, which was concluded the next week, saw Brookfield acquire NZ's gas distribution and storage network - including a 4800km gas distribution network, the Ahuroa gas storage facility (which can store up to 7 petajoules [PJ] of gas), and the country's largest liquified petroleum gas (LPG) retail supplier - for around $2.2 billion. Soon after, Minister Watts said he was "open minded" about whether it's a small or large-scale facility. The implication here is that while the purpose for establishing the facility is to help shore up national energy security, once the terminal has been built then it could just as easily expand to provision of gas to other consumers, possibly even including new commercial and residential consumers.

Seller Igneo Infrastructure acquired the assets in 2016, and had been trying to sell its stake for a number of years, and reporting from the New Zealand Herald (8/10/25) suggested that the transactions "represent that conclusion of a four year effort ... to quit the business". Igneo Infrastructure is a global infrastructure manager of First Sentier Investors Group, ultimately owned by trillion-dollar Japanese Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group.

Ban Motivator For Sale

The 2018 offshore ban was likely a major motivator for the sale, as a gas distribution network in a country whose gas is fast running out could be seen as a "stranded asset", that is, an asset that suffers an unanticipated or premature write-down or devaluation. The 2025 LNG commitment helped reverse any devaluation, altering the long-term cash flow assumptions for the network.

Both Brookfield and Igneo attended the Government's infrastructure investment summit in Auckland in April 2025, although it is unclear whether the deal was discussed during the summit. Treasury documents on the summit highlight the renewable energy focus (no new renewable projects were announced), but it would be ironic if the summit's main output was playing played private equity matchmaker to fossil fuel investors. Profits earned by any party to the deal have not been explicitly published.

Brookfield is not totally new to NZ. Brookfield-owned construction company Multiplex was involved in a number of major projects like Sylvia Park (over which it was sued for $540m by Kiwi Income Property Trust), facilities manager BGIS New Zealand was owned by Brookfield from 2015 to 2019, and in 2019 it partnered with Infratil to purchase Vodafone NZ (now One NZ), but sold its holding in 2023. Around the time of the summit Brookfield announced a billion-dollar joint venture with Tainui Holdings to develop the Ruakura Superhub, a logistics precinct in Hamilton with rail connections to the Ports of Auckland and Tauranga.

Tax Haven Ownership

It's fair to say that Brookfield has its share of tax concerns. A 2023 report by the Centre for International Corporate Tax Accountability and Research (CICTAR) noted "a heavy reliance on offshore related party debt to reduce income tax obligations where profits are earned, and shift interest income offshore or into other tax-free structures". Many subsidiaries are incorporated in tax-free Bermuda, as well as others in the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Gibraltar, Luxembourg and so on.

Tax haven ownership is not new territory because the ownership of our gas network is unclear. First Gas is owned by a chain of NZ-based subsidiaries and its reporting entity "First Gas Topco Limited" is majority-owned by an entity called the "Butterfield Trust (Cayman) Limited", incorporated at 27 Hospital Road in George Town, the Cayman Islands. Ultimate ownership traces back to Australia.

Extending the lifespan of NZ's gas infrastructure, of course, has clear climate implications for New Zealand, where difficult-to-abate agricultural emissions play such a significant role in the carbon budget. Sustaining - or even increasing - the number of residential gas connections and the use of gas at the residential level puts further pressure across the carbon budget.

Sustaining the residential gas frontier also has implications for human health. A recent report from the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority looking at the health impacts of gas stoves and unflued gas heaters estimated a total social cost of indoor air pollution from combustion appliances to be in the order of $5 billion per year.

Bolstering Value Of Fossil Fuel Infrastructure

It seems a matter of major concern that our Government's energy policy seems to be bolstering the value of fossil fuel infrastructure. As we hurtle towards climate breakdown, Governments' climate and energy policies should promote decarbonisation as much as possible, not breathe new life into sectors that were considered in decline. The fact that we may be doing this to line the pockets of foreign mega investors with a history of shadowy tax planning raise further questions. If only somebody would ask them.

Watchdog - 170 December 2025

Non-Members:It takes a lot

of work to compile and write the material presented on these pages - if

you value the information, please send a donation to the address below to

help us continue the work.

Foreign Control Watchdog, P O Box 2258, Christchurch, New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Email