Light Handed Regulation And Work Safety

A Case Study – Rail Safety In New Zealand 1974-2000

- Hazel Armstrong

Presented 8th October 2012 to the NZ Fabian Society in Wellington

A career in the railways was regarded as a job for life, but over the five years, from the middle of 1995 to the middle of 2000, 11 Tranz Rail workers had given their lives for their job: Jack Neha, Thomas Blair, Murray Spence, Ronal Higgison, Bernie Drader, Paul Kyle, Nigel Cooper, Graham White, Ambrose Manaia, Neil Faithful and Robert Burt. I was sitting in the tea room of Maritime House on Wellington's wharf in May 2000, having morning tea, when I heard about Robert Burt’s death. He was the fifth Tranz Rail worker killed at work in 12 months. Some months before I had set up practice as a lawyer at Maritime House, the offices of the Rail and Maritime Transport Union and the Seafarers Union. Leonie from the union office came in to the tea room and told us that Robert Burt had been caught under a train while shunting at the Middleton Freight depot in Christchurch and was dead. He had stepped up onto the foot plate and slipped and fell under a moving wagon connected to a remote controlled locomotive as he was trying to re-board the wagon.

On 27th November 1999, a Labour government had been elected. The Rail and Maritime Transport Union called for a Ministerial inquiry into safety in Tranz Rail. On 28 June 2000 the Minister of Labour, Margaret Wilson, announced that an inquiry would examine the causes of the fatalities, and the overall poor safety record of Tranz Rail. It would also make recommendations for improvements. Operating practices in any industry will change over time in response to new technologies, commercial pressures and the like. All of these pressures were impacting on Tranz Rail during this period, but while they may have been contributory factors, this presentation looks at the impact of deregulation on work safety, using rail safety as a case study. I have to go back to 1974 to give context to this story and the events that led up to the Ministerial Inquiry in 2000.

Will Hutton, a UK commentator, wrote in the Observer (18/9/11): “This entire financial edifice underwritten by tiny amounts of capital has been created over three decades backed by the theory that markets do not make mistakes. Capitalism is best conceived and practised, runs the theory, by hunter gatherer bankers and entrepreneurs owing no allegiance to the State or society. This is nonsense. Business and the State co-generate wealth in a system of complex mutual dependence. Markets are beset by mood swings and uncertainty which if not offset by Government action lead to violent oscillations. Capitalism without responsibility or proportionality degrades into racketeering and exploitation”. Will Hutton could be describing the havoc the hunter gatherer bankers and entrepreneurs created within rail in New Zealand over the 30 years from the mid 1970s to the 2000s. I want to describe what happens when rail safety is deregulated, when Government takes a passive role, and managers are thrust to the fore to manage safety. I think it is a story where neither the Government nor the rail employers acted responsibly and, as a result, safety was degraded.

Distancing Rail From The State

In 1974, Roger Douglas was a Labour Minister. He headed a caucus committee which was considering a new direction for NZ transport. A report sponsored by the caucus committee recommended reorganising the Railways Department into a public corporation, and it recommended the removal of the 40 mile limit on road transport. It suggested a significant alteration of the role that Government played in the transport sector. In 1974 rail was protected by Government regulation from competition from road haulage. In 1974 goods hauled for over 40 miles had to use rail.

Labour lost the 1975 election so Roger Douglas was unable to pursue the recommendations of the caucus committee report. Rob Muldoon, the Leader of the National Party became Prime Minister. In 1977, he changed the haulage requirement. It was extended to allow trucks to replace rail for haulage lengths up to 150 km. This opened up road haulage for the profitable links between Auckland to Hamilton, Hamilton to Tauranga, Christchurch to Ashburton. It affected 20% of rail traffic. In 1982 Prime Minister Muldoon deregulated the advantage that rail had over road by removing this stipulation entirely. This became effective from 1 June 1984. In the same year he also took the first step towards privatisation of New Zealand rail with the creation of the NZ Railways Corporation. It took ten years, including a change in Government, for the Roger Douglas report to be fully implemented.

Prime Minister Muldoon called for a snap election in 1984. Richard Prebble, the Opposition Labour spokesperson for rail, campaigned against rail deregulation. He toured the country on behalf of the Labour Party supported by the National Union of Railwaymen. I remember The New Nation, the Labour Party paper, displaying a photograph of Richard Prebble hanging on to the side of a train, doing a whistle stop tour to “Save Rail”. Murray Horton wrote in Watchdog 110, December 2005 of that campaign:

“In 1984, my union, the then National Union of Railwaymen gave $40,000 to Labour to get it elected. In 1984 he (Prebble) led a march of several thousand railway workers and their families through Christchurch as part of the union’s and Labour’s nationwide ‘Save Rail’ campaign. Well, Prebble did save rail – he saved it for the Yanks to whom the next National government sold it for a song and they proceeded to asset strip it to such an extent that it became a national disgrace and a danger to the few remaining workers, its own passengers and the general public. Prebble did his job so well that there is no longer any such Cabinet portfolio as Minister of Railways”.

Preparing For Privatisation

There was a gulf between what Richard Prebble had in his mind when he campaigned to save rail, and the unions who supported him. Labour won the 1984 snap election, with David Lange as Prime Minister and Roger Douglas as Minister of Finance and Richard Prebble as the Minister for Railways. Richard Prebble embarked on a series of actions which did not uphold his campaign slogan to “Save Rail”. Upon election in 1984 the NZ Railway Corporation commissioned a US consultancy firm, Booz, Allen and Hamilton, to review the effectiveness and efficiency of rail operations. Its brief was to build a commercially viable rail system in the newly deregulated market. A number of cost saving measures were suggested. A common theme was cutting staff numbers.

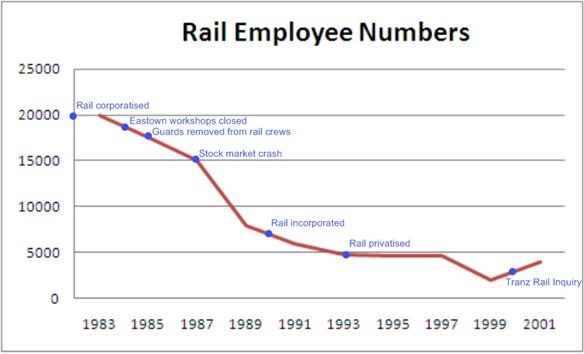

They suggested: eliminating guard vans, reducing shunting crew sizes, reducing the use of firemen, operating higher powered locomotives in multiple (without using two crews), increasing train size, selectively increasing weekend operations. Wayne Butson, the Secretary of the Rail and Maritime Transport Union told me: “The Booz Allen report was the death knell of the railway system. We never saw it at the time, we all knew it was bad but with hindsight we see now it was World Bank ideology. We felt betrayed, not only with the Booz Allen report but by Richard Prebble and Russell Marshall, Labour Cabinet Minister and MP for Wanganui, who oversaw the closure of the Wanganui workshop. There were security guards everywhere. There is no rail in Wanganui now; the trains don’t go over the bridge anymore”. Richard Prebble was determined to drive through the changes and in 1986 as Minister of Transport he threatened to close down the entire system unless rail was prepared to embrace technological change and become more efficient. Between 1983 and 1990 railways reduced its staff by 60%.

Reducing Crew Sizes

In 1985 the crew size on freight trains was reduced from three to two. Crews had been made up of one or more on locomotives in the front and a guard’s van in the rear. The guard’s van was removed. Then the crew was reduced to one. In 1989 shunting crews were reduced from five to three. Shunting hand signals were replaced by radio control. From the 1900’s until 1989 shunting practices had largely remained unchanged. It involved a locomotive with two crew and three to five people on the ground to do hand signalling. The locomotive engineer would continuously watch the senior shunter who, in turn, watched other members of the shunt gang. This maintained a line of sight and should a shunter disappear, the locomotive engineer would stop the movement. There were less accidents with this level of crew.

To deal with busy yards there were two types of shunting, namely push pull where wagons are coupled to the locomotive engine for the full duration of the movement (safe but slow) and loose shunting where momentum is relied upon. This is fast and dangerous. The faster the loose shunting is carried out the higher the risks. To get the job done quickly loose shunting was practiced. In 1989 management wanted to reduce the crew from five to three but this meant that hand signals could not been seen at all times. There were blind spots. Management replaced hand signals with radio contact. Initially, a shunting crew became one locomotive engineer and two shunters.

There were communication problems as many of the shunters had English as a second language, bad weather interrupted the radio communication, and some of the radios were faulty. Remote control replaced the locomotive engineer in the cab. Shunting was now carried out by two people. Incidents occurred because line of sight was not maintained, and there was too much reliance on radio contact and voice commands. There once were five in a crew, then three, then two. The driving pace of change, and staff reductions, was opposed by the union on safety grounds.

In 1988 Roger Douglas announced an economic and social package that promised to reduce Government debt by $14 billion. This was to be achieved by the privatisation of State assets. Treasury strongly advocated the privatisation of Government trading activities. Treasury wanted increased competition to stimulate the Railways to adapt to customer’s needs and reduce costs, thereby making users more internationally competitive. Treasury concluded that there was no apparent public policy reason for continued Government ownership of NZ Rail. By 1989 Treasury had a plan that rail should be reorganised into a “sellable” asset.

In March 1990 Richard Prebble introduced the New Zealand Railways Corporation Restructuring Bill into Parliament. The Bill empowered the restructuring of the NZ Railways Corporation. It allowed the Corporation’s core railway business and other business units to be placed in a fully commercial environment. The Bill empowered the Minister of Finance and the Minister for State Owned Enterprises to form one or more limited liability companies under the Companies Act and to hold shares in those companies. It also enabled the Corporation’s assets and liabilities to be transferred from the Railways Corporation to the Crown or to those new companies. In due course the Bill became an Act, the Railways Corporation was restructured to become the NZ Railways Ltd, and in 1993 the core railway business was sold to a private operator. Labour lost the election in 1990, but the programme for privatisation continued with the National government. NZ Railways Ltd began selling equipment and leasing it back, selling land and rail workers’ houses.

Health And Safety – A Tradeable Item

Health and safety at work was not highly regarded by those doing the restructuring and privatisation. The privatisers saw regulation as standing in the way of human freedom and opposing economic progress. In 1992 new health and safety legislation was passed, the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 (HSE). It imposed a duty on all employers to take all practicable steps to prevent harm to their employees. But rail employers were exempted from the new health and safety legislation, by an amendment to the Transport Services Licensing Act (no 3) 1992 (the TSL Act). This Act exempted rail employers from the requirements of the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 once the rail operator had an approved safety system. The TSL Act had a significant impact on safety in rail. It reduced the safety requirements on rail employers compared to other employers.

Exemption from the HSE Act meant the employer, could set its own safety rules, and vary them from time to time. The employer did not have to provide its safety system in its entirety to the officials who regulated safety in transport, the Ministry of Transport and the Land Transport Safety Authority. It did not have to take all practicable steps to manage hazards at work, it only needed to take whatever steps it deemed reasonable taking the cost of those steps into consideration. It could get by managing only the most significant hazards likely to cause significant injury or death, rather than managing all hazards that could cause harm. The employer would not be subject to Department of Labour inspections and would be free of prosecutions taken under the HSE Act so long as they complied with their own Approved Safety System.

The hallmark of deregulation is getting the State out the workplace because the employer knows best how to manage their workplace safely. Deregulation created an environment where the employer could set the safety rules, with limited oversight. There was no public awareness of what was happening with rail safety in the 1990s. This obscure amendment was passed without comment by politicians on either side of the House. It made the rail workers feel isolated. Wayne Butson from the RMTU described the feeling: “Being a worker for rail was much maligned. You were a State bludger: it wasn’t a pleasant time to be around”.

The legislation’s innocuous title and the speed of change all combined to hide the significance of this amendment, which exempted rail workers from the Health and Safety in Employment Act. This legislation allowed an environment to flourish that ultimately led to a fatality record that was eight times that of the national average (39.3 deaths per 100,000 workers compared with 4.9). Tranz Rail, unlike other employers in NZ had set their own safety rules since 1995, and the transport regulator was weak and ineffective against the dominant transport operator.

Exempting Rail Workers From The Health And Safety In Employment Act

I think the story behind the exemption of rail workers from the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 has not been told publicly before today. In 1992, NZ Rail Ltd was State-owned and was being prepared for sale, which took place in 1993. The consortium which bought NZ Rail Ltd named it Tranz Rail Ltd. It was a powerful organisation and with allies in the Ministry of Transport. The exemption of rail employees from the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 was never fully debated in Parliament. It is plausible that the Opposition Labour Party did not even realise what was happening, or they supported it at that time. The debate provides no insight into the Labour Opposition’s thinking on the exemption of rail workers from the Health and Safety in Employment Act.

The Transport Safety Bill came into the House for its first reading on 12 December 1991. The Bill contained a number of disparate changes to transport law including the introduction of random breath testing. The original Bill, as introduced to the House for its first reading, required every application for a rail service licence to be accompanied by a copy of the actual safety system. It also required the rail operator to identify who within the rail service operation was responsible for implementing and carrying out each part of the safety system. The new rail safety regime was largely ignored by those debating the Bill at the first reading in Parliament. The debate concentrated on random breath testing. In order to find out what happened between the first and second reading of the Transport Safety Bill, I applied for information under the Official Information Act, and called up people to get the story. This is what I could piece together.

The Behind Scenes Manoeuvres

NZ Rail wanted rail workers exempted from the Health and Safety in Employment Act. It appears that NZ Rail was lobbying the Department of Labour which oversaw that Act. A memo written on 29th June 1992 by Rex Moir, an official within the Department of Labour, argues that the railway safety regime could include the safety and health of rail employees. JD Adlam, a lawyer from Rudd Watts and Stone, provided advice to his client, NZ Rail Ltd, which was addressed to Murray King and R Ryan on 22 September 1992, advising NZ Rail Ltd that it would be preferable if NZ Rail Ltd only had to comply with the transport safety legislation. He advised that the Transport Safety Bill would need to be amended to include a section which deemed compliance of the Transport Safety Act to meet the requirements of the Health and Safety in Employment Act. He provided a draft of a proposed section to achieve the objective.

A behind closed doors meeting was held on 29 September 1992 attended by Department of Labour officials, Keith McLea and Rex Moir, NZ Rail Ltd represented by Murray King and R Ryan and Alan Malthus from the Land Transport section of the Ministry of Transport. NZ Rail Ltd, at this stage was a State-owned corporation readying itself for sale. The disclosed document shows that NZ Rail Ltd and officials from the two safety agencies agreed that compliance with the Transport Services Licensing Act could be treated as compliance with the Health and Safety in Employment Act.

However, it seems that the Department of Labour had second thoughts. On 12 October 1992 the Select Committee was told that officials from the Department of Labour considered that the HSE legislation should prevail. Chris Hampton, who headed Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) within the Department of Labour followed this up with a memo to the Minister of Labour, Bill Birch, dated 20 October 1992. He told the Minister that NZ Rail Ltd wanted rail employees excluded from the HSE Act. The Department of Labour by now was clear that rail employees’ health and safety would not be best addressed by the regime being proposed by the Transport Safety Bill. Chris Hampton gave Bill Birch two options: either redraft the Transport Safety Bill to exempt rail employees, or agree to the status quo which would mean that rail employees would be covered by the Health and Safety in Employment Act.

Official Information Act requests for all Select Committee minutes do not reveal what actually happened in the Select Committee room. There was no Labour Opposition minority report about the proposed exemption of rail employees. The Select Committee recommended to Parliament that NZ Rail needed only to describe the proposed safety system, rather than actually provide it to the safety regulator. It also recommended that compliance with the proposed safety system was deemed to be compliance with the Health and Safety in Employment Act. Further, the rail operator need only to have a “management system or structure responsible for implementing and maintaining the safety system, it didn’t have to specifically identify who would be doing what to preserve safety”. These were significant changes, and it seems that NZ Rail got what it wanted. The Department of Labour was sidelined.

These changes were presented to the House, but in the second reading, the changes were not debated. The legal basis for the exemption of rail workers from the Health and safety in Employment Act was found in section 6H of the Transport Services Licensing Amendment Act (no 3) 1992. “6H. Relationship between this Act and Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 - If a rail service operator or any other person complies with the provisions of this Act or of the operator’s approved safety system then, in respect of the matters governed by those provisions, such compliance shall be deemed to be compliance with the provisions of the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992”.

In the second reading debate, Richard Prebble (who was part of the Labour Opposition) said: “I rise to speak to this omnibus legislation which is what we now call it. It actually includes a number of Bills, and I shall start with a gripe. I think that limiting second reading speeches to 15 minutes means that a Member cannot do justice to legislation of this sort. Speeches should be given about railways and the like and I am afraid that I do not have the time to do so”. The limitation of speeches to 15 minutes is more significant because of the changes made to the Bill by the Select Committee. Richard Prebble did not use his 15 minutes to promote the safety of rail employees. Section 6H came into effect from 1 April 1993.

The Employers’ Safety System

A somewhat bizarre addendum is that in their haste, the Ministry of Transport official, Leo Mortimer, told the Select Committee Chair, that the Transport Safety Bill had omitted the transitional provisions required to cover the period from the enactment of the legislation and the approval of the safety system. A hasty amendment was made, but it did not completely repeal the Department of Labour inspectorate’s role until the safety system had been approved. Therefore, for the period 1993 to 1995 the Department of Labour was the inspectorate, and rail employees were not exempted because the employer had not succeeded in creating a safety system capable of approval by the regulator. To be exempted from the Health and Safety in Employment Act, the rail employer must have an approved safety system.

In 1995 the safety system was approved by the Ministry of Transport, and Tranz Rail employees were accordingly exempted from the HSE Act. The union was not given an opportunity to consider the safety system prior to the approval. It turns out that the approved safety system was a mirage. It did not really exist. In effect, Tranz Rail had described an operating system to the regulator, but the critical point that was overlooked by the regulator was that Tranz Rail was submitting to them an operating system, not a safety system. The regulator did not approve a safety system in reality.

Despite its efforts to view the “approved safety system”, the union was not able to view it. The regulator had been given a description of the safety system, not an actual copy of the safety system (because it did not exist). The Ministry of Transport had signed a confidentiality agreement not to disclose the approved safety system which it did not have. If the regulator had decided it wanted to see the approved safety system (which it did not choose to do) it would have had to ask Tranz Rail’s permission to visit the Tranz Rail library to see a copy of the operating documents. The regulator may have discovered that there wasn’t an approved safety system. The regulator had not taxed its mind as to whether the safety system that it approved was a tangible document capable of review. In the absence of a separate and formal safety system, safety and health took second place to operating the network.

The Sale Of Rail

In 1993, the Government announced the sale of NZ Rail Ltd to a consortium of Fay Richwhite, Wisconsin Central Transportation and Berkshire Partners. Fay Richwhite was a financial advisor to the recently incorporated NZ Rail Ltd, but Treasury decided that Sir Michael Fay and David Richwhite may have had an unfair advantage as they were both advising NZ Rail and were also part of the consortium which purchased NZ Rail in 1993. However, this concern was not acted upon. Ian Jack a UK writer for the Guardian described the UK sale of rail as: “sold off hastily, cheaply and carelessly”. A stunning parallel with the NZ sale of its strategic asset. In 1995 the new rail owner rebranded the company as Tranz Rail: Wayne Butson says: “It was just another name change again, just another paint job for the locos. Ed Burkhart was the Director of Tranz Rail in the 1990s, there was a whole succession of US management coming in and telling us they know ‘the right way to run a railroad’”.

The Impact Of Deregulation On Safety Of Rail Workers

In the first part of the presentation, I have set out the steps that the Government took to distance itself from running a railway from 1974 until the sale of rail. We then covered the reduction in safety standards within rail during the same period of time, and we looked at how the company, NZ Rail Limited ensured there was not effective regulatory oversight of rail safety. I started the presentation quoting Will Hutton, he says: “Capitalism without responsibility or proportionality degrades into racketeering and exploitation”.I now want to take you through the impact of deregulation on the safety of rail workers. In this section, I am focusing on the five years after the sale of rail up to the time of the Inquiry.

In 1995 Jack Neha was killed in a shunting accident. He had worked as a locomotive engineer, but became a shunter rather than take redundancy. He had had six weeks on the job training. The reduced crewing meant he was the lone shunter on the ground. There was no back up for Jack. The Department of Labour investigated the circumstances of Jack Neha’s death and prosecuted Tranz Rail. The two shunters who had showed Jack the ropes told the Court that they had warned the terminal manager that Jack was not ready for shunting. Tranz Rail had dropped the third man in the shunting gang in 1989. District Court Judge Evans imposed a record fine of $30,000, saying that Tranz Rail’s decision to remove the “wicket keeper” in the shunting gang meant it was inevitable that someone would be put at risk. Tranz Rail appealed against the level of the fine; the High Court reduced it to $15,000.

In 1995 Russell Wall was on the front of a remote controlled engine shunting containers when a front end loader blocked the track in front of him. He was thrown onto the track in the collision and then run down by the remote controlled unit. He said after the event, “when it stopped I can’t describe the feeling, my God I am still alive.” Russell was off work for more than six months. In 1996 and 1997 there were eight serious rail accidents. In 1999 Graham White died when two trains collided head-on at Waipahi. In 1999 Ioasa Iuni was seriously injured when a hand grab that he was holding came off because a corroded nut broke free. Mr Iuni fell into the path of the train and as a result had to have his leg amputated. The Department of Labour prosecuted and Judge Perkins found that Tranz Rail had failed to comply with its approved safety system (1) . Tranz Rail pleaded guilty. It was fined $27,500.

Crushed To Death

In 2000 Ambrose Manaia was crushed to death in the Wellington yards when he was caught between the locomotive engine and an articulated truck. Mr Manaia was a shunter, and another person was operating the locomotive engine by remote control. There was a fault in the remote control unit which meant that he couldn’t get full power from the locomotive. So he took manual control of the locomotive. He got the all clear from Mr Manaia to move forward and did so, but a truck had moved onto the track. He applied the brakes but it was too late and as Mr Manaia was on the front plate of the locomotive he was caught between the engine and the truck. At the Coroners hearing an expert gave evidence and he identified the problem of increased risk operating as a two man crew when one was in the locomotive. It is likely he thought that when Mr Manaia gave the all clear he did not have line of sight and he did not see the truck approaching the track. The road and rail layout were not separate, there were no barriers to prevent the truck crossing a rail siding when it was being used for shunting.

The Coroner recommended that the Approved Safety System should be a viewable document which was accessible, and that the operation and crewing of locomotives during shunting be subject to review. In 2000, while the Tranz Rail managers were considering ways of reducing the workforce before Christmas, there was something incredible unfolding on the West Coast. The local bridge gang were just starting their holidays, when an observant track worker noticed the bridge behaving abnormally. As the train passed over, one side of the pier bent to such an angle that he thought the train was going to fall off. On inspection it was found that one of the studs had decayed leaving a very thin shell to support the bridge. When a train passed over the stud it was crushed a little more each time.

Ministerial Inquiry

I became legal counsel for the Rail and Maritime Transport Union to assist them with the Inquiry assisted ably by lawyer Sue Bathgate (now Sue Robson). The workers and the union gave evidence at the inquiry. Wayne Butson told the Inquiry: “The union’s requests for the approved safety system were blocked. The exchange of documents as part of this inquiry revealed that the Land Transport Safety Authority and Tranz Rail had formed a memorandum of understanding that contained a confidentiality agreement that operated to block union requests for the approved safety system documents”.

A locomotive engineer said: “The danger is multi-skilling. I was a good locomotive engineer but as a shunter, I was a liability. The jobs have separate skills and the training has to be adequate so I could perform at a level so I could have been efficient and safe”. Another said: “Locomotive and wagon maintenance had deteriorated under Tranz Rail. Important safety parts of wagons such as hand grabs and foot steps were being left unrepaired for too long when damaged. I regularly saw wagons marked up and bad ordered left unrepaired for weeks, which should not have been the case if Tranz Rail’s safety protocols were adhered to”.

A 2nd grade locomotive engineer thought: “Because Tranz Rail ran with the bare number of locomotives necessary, it was difficult to get them out of service for repairs; it was not until an engine completely broke down that the problems could be addressed”. Another locomotive engineer said: “Some classes of locomotive restricted the vision of the sole locomotive engineer (because they had been built for two). This meant that trains were being driven at full speed by drivers who had no clear view of the left side. On top of this, shifts were lengthened to the point where they were hazardous to health and safety. I can safely state that night shift Tranz Rail drivers have slept at the controls of moving trains”.

The same driver said “I reported a rogue fault in the track when I was driving a passenger train. A week later I noticed the fault had not been fixed nor had speed restrictions been put in place. I again reported it to train control. It was not until the third time I noticed it and reported it that the fault was actually fixed”. A common theme was that there was pressure to ignore or sideline safety, if it impinged on efficiency or profit in any way. The Palmerston North Branch spoke to the Inquiry about the toll on their members.

Falling To Bits

“Staff have been constantly threatened with redundancy, restructuring, job cuts and retraining. The resulting pressure and stress placed on some staff had become intolerable. The Branch Secretary said that Tranz Rail had played a role in the suicides of several Tranz Rail employees. The Palmerston North Branch Executive was faced with employees reduced to tears and in states of depression caused by the constant restructuring”. A train examiner from the Wellington yard said: “I believe that if we did have the power to bad order wagons for things other than brakes, which is where we have been told to confine our attention, a lot of the wagons would not be moving on the railway in New Zealand at all and that is because there are many, many, many wagons that have things wrong with them. For example, I have seen photos from the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) report of the nuts and bolts that gave way in the Ioasa Iuni accident in the Wellington yard the year before last and I would have to say it is not difficult to find wagons with nuts and bolts in that condition on many wagons in the yards.

“I believe another reason why we are confined to simply carrying out a brake inspection as our primary job is because the staff has been reduced over the years to one fifth of what it was and in my opinion that is simply not enough people to do the work that is required…I believe that health and safety issues are not allocated a high priority by the Company. The reason I believe this is because of my experience of repeatedly raising matters of health and safety concern about conditions in the Wellington yard and just not having any response from the Company on addressing those concerns and most importantly. Obviously, not having things repaired so that accidents do not happen.

“I will give you some examples of things that are not safe in our yard… the yard is of an old design and it is built on reclaimed land. What this means is that we have sleepers sinking and the rail basically just falling off…on the rail connection plates where there should be four bolts, the majority may have two or three bolts; there are very few that actually have four bolts, there are rotting sleepers and the ballast crushed down which causes the track to become unstable, there is a complete lack of ongoing maintenance in the yard. The only maintenance that is done seems to be done on an emergency basis like when the train simply cannot run any more then a running repair will be done but not a permanent repair job... there are potholes and debris right through the yard; all sorts of sizes and shapes of potholes and boulders. In 1996 I got fed up with constantly raising issues about our working conditions and safety problems in the yard so we all got together and we wrote up a document for the company and most of the people in the yard signed that document. It was handed to the company and some time after that we were told that after the new stadium plans were finalised (the Cake Tin. Ed.) the Wellington yard design would be addressed. The stadium is long since built and the yard design has not been addressed at all as far as I know. Another time that we raised safety issues we made up a book of four pages of work. I think that we identified over 130 jobs that needed doing in the Wellington yard maintenance wise. ….I know some of us are reluctant to do anything that could be considered to be stirring by the Company because we are worried that that means we will be marked out and the next time there is a restructuring we will lose our jobs”.

Winning The Roger Award

In 2000, Tranz Rail applied to join ACC’s partnership programme. ACC was not prepared to agree to their application. ACC provided Tranz Rail with a safety advisor to advise Tranz Rail what it would need to do to obtain accreditation. In 2000, Tranz Rail was awarded the Roger Award for the second time. This award was given because the judges thought Tranz Rail’s safety record was appalling. A major factor in their decision was that Tranz Rail’s concern was solely for profits. They said: “It is typical of Tranz Rail to asset strip, undervalue resources and over use them without replacement…Tranz Rail’s callous and calculated attitude towards workers is still a problem at Tranz Rail. Tranz Rail has killed more New Zealanders than those lost in the Army’s deployment in East Timor…the fatality rate at Tranz Rail is 39.3 per 100,000 employees, this is eight times the national average“.

Tranz Rail won the Roger Award for the Worst Transnational Corporation Operating In Aotearoa/New Zealand three times, in 1997, 2000 and 2002. The 1997 Judges Report is not online but the 2000 and 2002 ones are, at http://canterbury.cyberplace.co.nz/community/CAFCA/publications/Roger/Roger2000.pdf and http://canterbury.cyberplace.co.nz/community/CAFCA/publications/Roger/JudgesStatement2002.html respectively. In those early years of the Roger Award Tranz Rail’s dominance was becoming an embarrassment and it was declared ineligible for further nomination and shunted (pun intended) into the newly created Roger Award of Shame, where it remains the only occupant. Ed.

After The Inquiry: Reregulation Of Rail Safety

The Section 6H exemption of rail employees from the Health and Safety in Employment Act was repealed on 5 May 2003. It had allowed a decade of lax safety standards for rail employees. The Inquiry led to Parliament changing the safety regime in rail. The Railways Bill came into Parliament in 2003 and became law in 2005. The Bill had cross-Party support except for the Act Party. Sue Bradford for the Greens said: “Much as some of us would like to turn back the clock on Richard Prebble and his friends and their selling rather than saving rail, all of us have had, alas, to learn to live with the consequences of that. The overarching intent of this Bill is to fix problem raised by the Ministerial Inquiry into Tranz Rail which reported back in late 2000 and the Halliburton KBR infrastructure review. While the language of legislation like this can be quite technical and dry I would like us all to remember the number of rail workers and passengers who have been injured, the workers who have died., and all the human tragedies that lie behind the commissioning of the Wilson Inquiry and the Halliburton KBR report which have led to this legislation”.

The Bill was opposed by Act; speaking on their behalf Deborah Coddington said: “But what will happen is that having a regulator responsible for all that will take the responsibility for the safety standards and the setting the compliance and vigilance for those standards away from the rail companies - the rail participants - and put them in the hands of a regulator. All the participants will be reduced to box ticking and ensuring the companies comply. As I said in the beginning it is hard to argue against safety and we do not argue against safety. But one always has to remember that safety comes at a cost. Under this bill safety is coming at a significant cost".

Pike River Tragedy Shows Nothing Has Changed

The RMTU described the changes that occurred after the Inquiry: “The Inquiry changed health and safety in Tranz Rail, union and management are committed to working together and some changes include: establishment of health and safety action teams; establishment of occupational councils to look at ways to proactively improve health and safety; occupational councils include a shunters’ council which has already had some success; establishment of a joint senior management union health and safety executive; a funded position in the union to solicit employee involvement in health and safety; Tranz Rail has taken steps to actively made amends to the families of those killed; a large reduction in the lost time injury rate per 200,000 working hours (from 11 to 5.6)”.. In the first 12 months following the Inquiry the RMTU and Tranz Rail achieved a 40% reduction in lost time injuries, a 30% decrease in injury severity and a reduction in operating incidents such as derailments.

Since this was written the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Pike River Mine Tragedy has issued its Report, which was damning of both that company and the whole official health and safety regime for underground mining. Ed. It is my view that the lessons from the Tranz Rail Inquiry are that it illustrates what happens when the regulators are ineffective and captured by the employer; when Parliament and the Government of the day are prepared to compromise worker health and safety for some other end game; when directors and managers turn a blind eye to hazards. A decade may have passed between the Tranz Rail Inquiry and the Pike River Tragedy, but what has New Zealand learnt in that decade?

Footnote

1. The failure to comply with the Approved Safety System gave the Department of Labour jurisdiction to apply the HSE Act. Section 6H says: “Relationship between this Act and Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 - If a rail service operator or any other person complies with the provisions of this Act or of the operator’s approved safety system then, in respect of the matters governed by those provisions, such compliance shall be deemed to be compliance with the provisions of the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992”.

Non-Members:It takes a lot

of work to compile and write the material presented on these pages - if

you value the information, please send a donation to the address below to

help us continue the work.

Foreign Control Watchdog, P O Box 2258, Christchurch, New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Email