DOES CAPITALISM HAVE LONG WAVES?

And Have We Entered One Of Decline Since The 2007-09 Crisis?

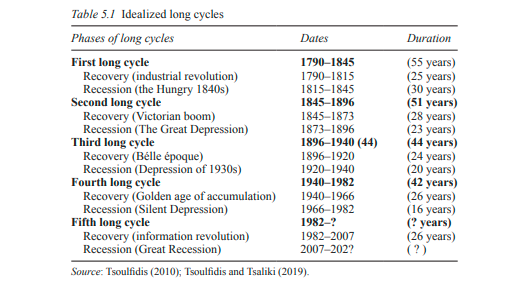

- Mike Treen

Industrial cycles of approximately ten years have been a remarkably persistent feature of capitalism since 1825. Marx, Keynes, and Schumpeter all agreed that periodic replacement of the elements of fixed capital, especially factory machinery, forms the material basis of the ten-year industrial cycle. About every ten years, there is a wave of renewal and expansion of fixed capital as new machines replace old machines in existing factories, and new factories filled with state-of-the-art machines are constructed. The resulting over-investment inevitably ends with the overproduction of commodities, leading to flooded markets.

Once the crisis breaks out, the formation of new fixed capital falls off rapidly. Even after the rundown of inventories leads to inventory restocking, there is still a large amount of idle overproduced fixed capital left over from the last boom. However, about ten years after the last boom, the need to renew a significant amount of now aging factory machinery kicks off a new boom that soon leads to over-investment in fixed capital, general overproduction of commodities, and crisis.

Material Basis For Short Cycle

The Kitchin inventory cycle, which is less pronounced, is also widely accepted among economists who study business cycles. Marx himself made occasional references to this cycle. Joseph Schumpeter called these cycles Kitchin cycles in his 1939 book "Business Cycles" after the statistician and South African mine owner Joseph Kitchin (1861-1932), who described them.

Since Kitchin, these inventory cycles have been widely accepted among bourgeois business-cycle experts. About every three or four years, inventories are overproduced, leading to a minor recession or slowdown, what the business press calls an "inventory adjustment."" A major recession occurs when a downturn in the Kitchin cycle coincides with a peak in the ten-year investment cycle of fixed capital.

These two cycles are called cycles rather than mere waves because each phase of these cycles necessarily leads to the next phase. While accidental factors certainly affect these cycles, and major wars can temporarily suppress them altogether, these cycles are not accidents but the necessary consequence of the capitalist mode of production.

Is There A 50-Year Cycle?

But what about the proposed 50-year cycle, often called the Kondratiev cycle after the Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev, who described them in the 1920s? First, do such cycles really exist? For it to be a true cycle, each stage of the 50-year cycle would necessarily lead to the next phase. Or do these cycles reflect accidental causes? If the latter is the case, they are not cycles at all. Assuming that long cycles exist, what would be the material basis of such a cycle? Does the capitalist economy of necessity give rise to such a cycle?

One explanation proposed by Kondratiev was that the 50-year cycle reflects the lifetime of very long-lived elements of fixed capital. Not all elements of fixed capital are actually replaced every ten years. It is not hard to find machines that are considerably older than ten years and still used in factories. Buildings and bridges certainly last much longer than ten years. In this case, the material basis of the long cycle would be similar to that of the ten-year industrial cycle. This theory has, however, won very little support among any school of economists, whether Marxist or bourgeois.

In his "Business Cycles," Joseph Schumpeter suggested that the 50-year cycle arises from a complex pattern of innovations. A wave of major innovations eventually peters out into a wave of minor innovations. The result is great waves of investment every 50 years that gradually taper off, leading to the depression phase of the Kondratiev cycle. Eventually, the depression in the cycle will prepare the way for a new phase of entrepreneurial innovations and a new upswing in the Kondratiev cycle. Schumpeter proposed in "Business Cycles" that the super-crisis of 1929-33 was caused, at least in part, by a trough in all three cycles that occurred in the early 1930s.

Ernest Mandel And Long-Cycle Theory

Marxist economist Ernest Mandel, starting in the 1960s, was more sympathetic to the concept of a long cycle. Mandel preferred the term long waves. But what factor would, according to Mandel, cause capitalist economic development - expanded capitalist reproduction - to be broken up into long waves lasting considerably longer than the ten-year industrial cycles?

Like many Marxists, Mandel was fascinated by Marx's law of the tendency of the rate of profit to decline. In Volume III of "Capital", Marx described this law as the most important law of political economy. This tendency for profits to fall over time became central to Mandel's explanation for why a period dominated by a series of strongly upward phases of the industrial cycle was succeeded with a period of stagnation.

Marx's Law Of The Tendency Of The Rate Of Profit To Fall

Long before the time of Marx, political economists had assumed that the long-term tendency of the rate of profit was downward. This was assumed even by later schools of economics, including the classical marginalists and Keynes. Only after World War II did it become popular among bourgeois economists to deny the historically downward tendency of the rate of profit. However, the reasons that Marx gave for the tendency of the rate of profit to fall were completely different than those given by bourgeois economists, whether before or after him.

Marx's explanation is an extension of his overall theory of value and surplus value. Suppose the level of labour productivity in all branches of production is unchanged. This will mean the value of commodities will be unchanged. If this is true, the value of such elements of capital as raw and auxiliary materials, machinery, and factory buildings is a mathematical constant. Marx called this kind of capital constant capital.

The other type of capital consists of the commodity labour power. Labour power alone produces a value greater than its own value. Workers not only produce a value that replaces the value of the capital they consume - the necessary labour - but a value above and beyond it, a surplus value, by performing unpaid surplus labour. This was Marx's greatest single discovery in economics, though he made many others. Behind the appearance of the exchange of equal quantities of labour, there is the same old phenomenon of unpaid surplus labour that marked chattel slavery, feudalism, and other forms of exploitative class society.

Unlike the value contained in raw and auxiliary materials, machinery, factory buildings, and so on, whose value is preserved in the reproduction process, variable capital creates additional value. The value represented by purchased labour power - variable capital - expands and, in mathematical terms, is, therefore, a variable, not a constant. However, not all the newly created value will represent additional variable capital; some will represent additional constant capital, which will, therefore, be unable to create additional value.

While classical economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo considered the primary division within capital to be between fixed and circulating capital, Marx, in contrast, discovered that the primary division within capital is between constant capital, which does not produce surplus value, and variable capital, which alone produces surplus value. Therefore, before the transformation of values - or direct prices - into prices of production, the rate of profit on constant capital is zero. Only variable capital will have a rate of profit of more than zero.

Marx then observed that over time, the ratio between constant capital and variable capital shifts in favour of constant capital. This causes what Marx called the organic composition of capital, the ratio between constant and variable capital, to rise. The real cause of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, however, is hidden from the capitalists engaged in everyday business, as well as the vulgar economists, by the transformation of values into prices of production - which gives rise to the illusion that both constant capital and variable capital produce surplus value.

All things remaining equal, the rate of profit will fall as the organic composition of capital rises, though various counter-factors tend to work in the other direction. Most important of these is the ratio of unpaid to paid labour, what Marx called the rate of surplus value, or the rate of exploitation. Over time, the rate of profit on the variable capital rises, partially offsetting the growth of the constant part of capital that yields no profit.

Another important counter-tendency is the cheapening of the elements of constant capital, which slows its rate of growth in value terms. Marx, therefore, distinguished the technological composition of capital from the organic composition of capital. The technological composition of capital rises much more rapidly than the organic composition of capital.

In addition, anything that increases the rate of turnover of variable capital, such as the opening of new markets or improved transportation methods, also increases the rate of profit over a given period, such as a year. Because there are counteracting factors, the falling rate of profit is only a tendency, according to Marx. Counter-tendencies can override it for a more or less prolonged period. Therefore, Marx's law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall does not rule out a rise in the rate of profit over considerable periods. Mandel built his theory of long waves on this foundation.

Mandel's Theory Of Semi-Cycles

Marx expected the rate of profit to fall only over considerable periods of time and not from year to year. Mandel held that the rising organic composition of capital leads to a fall in the value rate of profit sufficient to cause a considerable slowdown in the rate of accumulation of capital or economic growth after 20-30 years.

This slowdown is not accidental, according to Mandel, it is a necessary result of the most basic laws that govern the capitalist system. But why doesn't the stagnation or semi-stagnation simply last indefinitely or even gradually intensify as the organic composition continues to rise? Here Mandel turned to accidental factors that may or may not recur in the future. According to Mandel, each expansionary long wave of capitalist development historically had a different cause. The only thing these causes had in common was that they all temporarily increased the rate of profit, overriding the long-term downward trend of the profit rate.

According to Mandel (and Marx and Engels), the 19th Century gold discoveries in California and Australia led to an extremely rapid expansion of the capitalist market, or what comes to exactly the same thing, to a very rapid growth of monetarily effective demand. In the late 19th Century, the rapid spread of colonialism caused the profit rate to increase. The fruit of this rise in the rate of profit rooted in spreading colonialism was the wave of accelerated capitalist economic growth that began in the 1890s and continued to 1913.

The last long wave of capitalist economic expansion, the one that occurred between 1948 and 1967, Mandel believed was rooted in a sharp rise in the rate of exploitation and profit caused by the huge defeats that the working class had suffered in the years that followed World War I. These included the rise of a series of fascist and military dictatorships, especially the fascist dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, which crushed the working class movement throughout continental Europe.

This led to a sharp rise in the rate of surplus value, the ratio of unpaid to paid labour. The sharp rise in the rate of profit on variable capital had, for some time, swamped the effect of any rise in the growth of constant as opposed to variable capital that occurred during this period. This explanation works better in explaining the postwar prosperity in West Germany, the rest of Western Europe, and Japan than in explaining the boom in the United States. The inter-war years - leaving aside the special case of the Russian Revolution - were a disaster for the European working classes and perhaps the Japanese working class, where a military dictatorship was imposed in the 1930s and 1940s.

But they were actually years of great advance for the working class in the leading capitalist country of the epoch, the United States. The building of powerful industrial unions for the first time in basic industry, as well as winning unemployment insurance and social insurance, no matter how inadequate, by the US working class under the New Deal certainly made it more difficult for the US capitalists to raise the rate of profit by increasing the rate of surplus value within the United States. This is why the great majority of US capitalists viewed Franklin Roosevelt with bitter hatred.

But it is true that after World War II economic growth was much faster in West Germany and the rest of Western Europe and Japan, with the exception of Britain, than it was in the United States. Therefore, we can concede that there is some truth in Mandel's explanation regarding Western Europe and Japan. What we may call the Mandel theory of long waves is based on problems that the capitalist class faces in the production of a quantity of surplus value that is sufficient to maintain a value rate of profit high enough to maintain vigorous capitalist expanded reproduction.

Mandel did note in his book "Long Waves Of Capitalist Development" that the question of effective monetary demand - the realisation of surplus value in the form of monetary profit - should also be worked into the theory of long waves. However, Mandel did not do this in his book, concentrating only on the production of surplus value and the value rate of profit.

Fluctuations In The Production Of Gold

This brings us to what is perhaps the oldest explanation for long waves or long cycles: fluctuations in the production of money material - gold. According to Mandel, the Dutch Marxist Jacob van Gelderen - who Mandel credits along with Alexander Parvus as founders of long-wave theory - noticed that rises in gold production preceded accelerated waves of growth of the capitalist system. Karl Kautsky, in his book "The High Cost Of Living," also noted the relationship between rising gold production and periods of accelerated waves of growth of the capitalist economy, as well as the relationship between prolonged depressions and low gold production.

More recent Marxists, however, have generally ignored the role of gold production when they discuss long-cycle or long-wave theories. Mandel played down the role of gold production in his book "Long Waves", except for the 1848-1873 "expansionary wave". Modern Marxist economists, with few exceptions agreeing with most bourgeois economists on this question, have wrongly assumed that with the end of the international gold standard, the level of gold production no longer significantly affects the rate of economic growth. This leads to the view that any shortage of demand can be dealt with through Government deficit spending and, if there is a shortage of money, by simply printing more, up to "full employment."

If crises occur anyway, they must arise either because a section of the capitalist class opposes Keynesian policies - usually assumed to be the financial or money capitalists, who fear the effects of otherwise beneficial "mild inflation" because it tends to erode their incomes in real terms - or because an insufficient amount of surplus value is being produced to sustain an adequate value rate of profit.

In reality, the concrete data on the history of gold production from the 1848-51 gold discoveries onward show that periods of extraordinary economic crisis-depression have been preceded by declining gold production, just as eras of rapid capitalist economic growth have been preceded or accompanied by rising gold production.

This is true for the years examined by such early 20th Century Marxists as van Gelderen and Kautsky but also for the following years and decades. For example, a major drop in gold production during and immediately after World War I preceded the super-crisis of 1929-33. The rate of increase of gold production also began to stagnate immediately before the stagflation of the 1970s. The inflationary economic crisis of 1974-75 was preceded by declining gold production, and gold production remained stagnant at a depressed level until the economic crisis of 1979-82, after which it recovered.

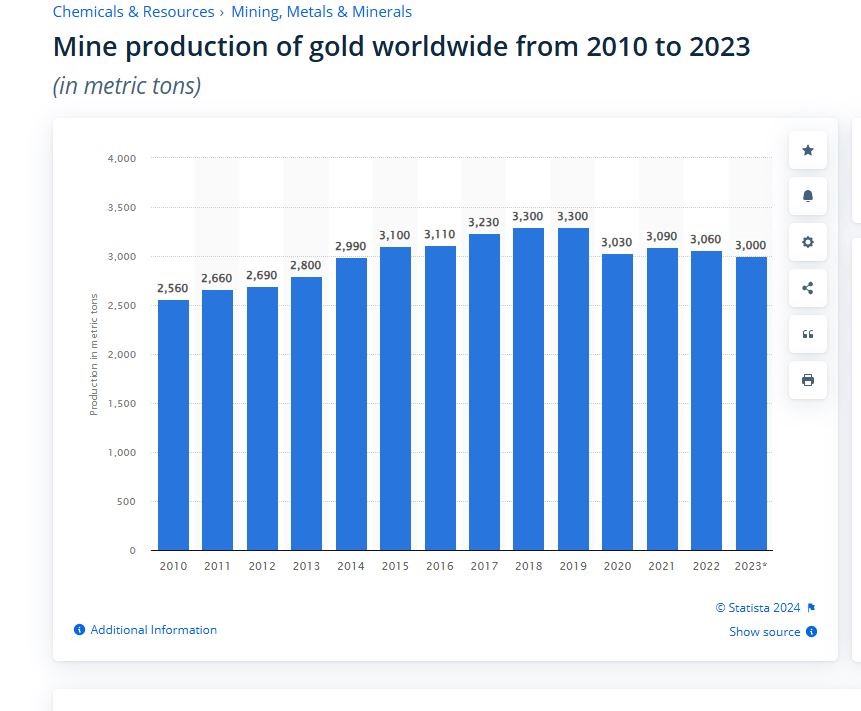

This pattern has been repeated in the 2007-09 Great Recession. Between the early 1980s and the turn of the century, the trend in gold production was strongly upward, and after the turn of the century, it began to decline. Within less than a decade after the economic crisis of 2007-09, though after that crisis, gold production resumed its rise and hit new highs in 2018.

Therefore, both our theoretical analysis and the concrete economic history since 1850 agree that the long-run rate of growth of the market is tied not to the rate of growth of commodity production, as Say's Law would have it, or the fiscal and monetary policies followed by Government and central banks as Keynesians and Keynesian-Marxists believe but by the rate of growth of the quantity of the money material - gold. This is true whether a gold standard in any form is in effect or a system of paper money prevails.

Contrary to the hopes and expectations of bourgeois economists, the end of the gold standard has not freed the growth of the market from its golden chains. This is shown by the economic "stagflationary" crisis of 1968-82 and was confirmed again by the 2007-09 world crisis. The level of gold production provides the missing piece in Mandel's analysis of long waves: the role of the growth or lack of growth of monetarily effective demand - the market.

Mandel, unlike most modern Marxists who either claim that gold has lost its monetary role with the end of the international gold standard or simply ignore the question altogether, specifically affirmed that gold continues to retain its monetary role and continues to function as the universal equivalent or measure of the value of commodities.

But except for the 1848-1873 long wave of expansion that occurred when the gold standard was in effect in the most important capitalist country, Britain, as well as the United States, Mandel played down the importance of the level of gold production on the rate of economic growth. The price he paid left a large hole in his theory of long waves that he acknowledged, the role of monetarily effective demand.

Is Gold Production Cyclical?

As a rule, after several industrial cycles dominated by the boom phases, the general price level rises above the value of commodities. This causes the rate of profit in the gold (money material) producing industries - mining and refining - to become less profitable than most other branches of industrial production. Capital, therefore, begins to flow out of gold production and refining.

As the production of money material declines, the quantity of money grows at an increasingly slow rate relative to real capital - productive and commodity capital. As a result, credit increasingly replaces money, eventually stretching the credit system to its limits. Money becomes tight and interest rates rise. This situation, assuming capitalist production is retained, can only be resolved by a crash or a series of crises and associated depressions of greater than average intensity, duration, or both.

One result of a crisis or series of crises of greater than usual violence or duration is a lowering of the general price level - measured in terms of the use value of gold bullion - once again to below the value of commodities. This makes gold production and refining industries more profitable than most other industries. Capital once again flows into gold mining and refining, causing the production of gold bullion to rise once again. The quantity of money then expands with low interest rates and "easy money".

As the process of liquidating the previous overproduction goes on, especially of those commodities that serve as means of production, the accumulation of (real) capital stagnates. As a result, for a period of time, money capital is accumulated at a faster rate than real capital. But once the accumulated overproduction - especially in the form of surplus productive capacity - is liquidated, a new "sudden expansion of the market" occurs leading to a series of industrial cycles dominated by the boom phases rather than the crisis or depression phases.

This "long cycle" is built into the commodity foundation of capitalist production and is the inevitable result of the commodity form itself once it is fully developed. But this cycle is also affected by accidental events such as discoveries of rich new gold mines and technological improvements in gold mining or refining that can either weaken or reinforce it depending on circumstances, as well as by such "accidents" as wars and revolutions.

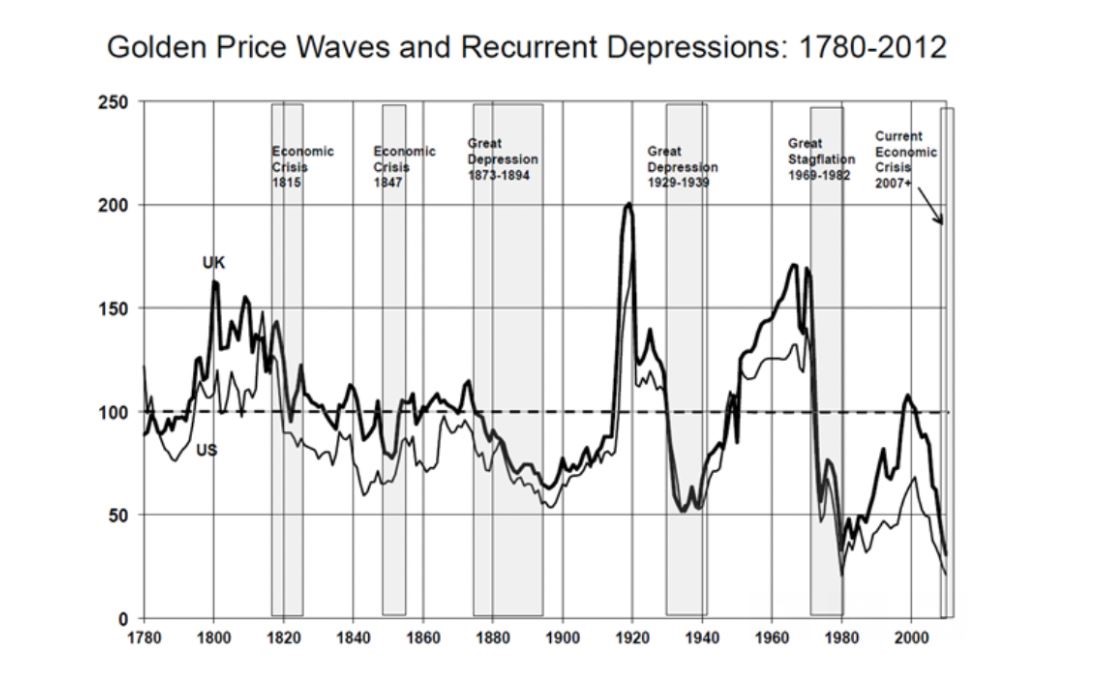

Another fine economist, Anwar Shaikh, who knows his Marx and supports an understanding of the history of capitalism involving long waves, produced a graph to prove his argument. He follows the long-term movement of wholesale prices in the US and the UK. He shows in his graph that there is a movement in wholesale prices upwards during a period of the long wave that is dominated by strong upturns in the business cycles and trends downward in prices during a period of the long wave where business cycles are dominated by the downward phase of the cycle.

The decline in wholesale prices is associated with a period of stagnation or long depression under capitalism. So, we have the 1825-1848, 1873-1896 decline, the Great Depression of 1929-1940, the Great Stagflation of 1970-1982, and a similar decline, which he argues indicates a new Great Depression, beginning in 2008, which he describes in a lecture as a "very scary" conclusion for his students at that time.

To produce an accurate version of the graph, he needed to measure the prices in terms of gold because, in the period following the abolition of the gold standard, there has been a permanent inflation in paper money prices that hides the real movement of prices in gold terms. This fits very closely with the arguments presented here even though Shaikh is broadly in the school that looks for the cause of crises in the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to fall.

Wholesale prices in gold terms in Anwar Shaikh's book Capitalism p 64

Conclusion

As I was finishing this article for Watchdog a blog site called Critique of Crisis Theory that specialises in Marxist economic theory came out with a blog dealing with many of the same issues I have. I have been helping edit a book on Marxist Crisis Theory by the blog's authors that will published progressively on this site.

They write: "Earlier in the 19th Century, we had the mid-Victorian boom that followed the discovery of gold in California in 1848 and Australia in 1851. This process was repeated in the years after the discovery of gold in the Klondike in 1896. Immediately after these discoveries, periods of generally falling prices and depressed economic conditions gave way to periods of rising prices, a rise in the rate of profit, accelerated economic growth, and high demand for the commodity labour power".

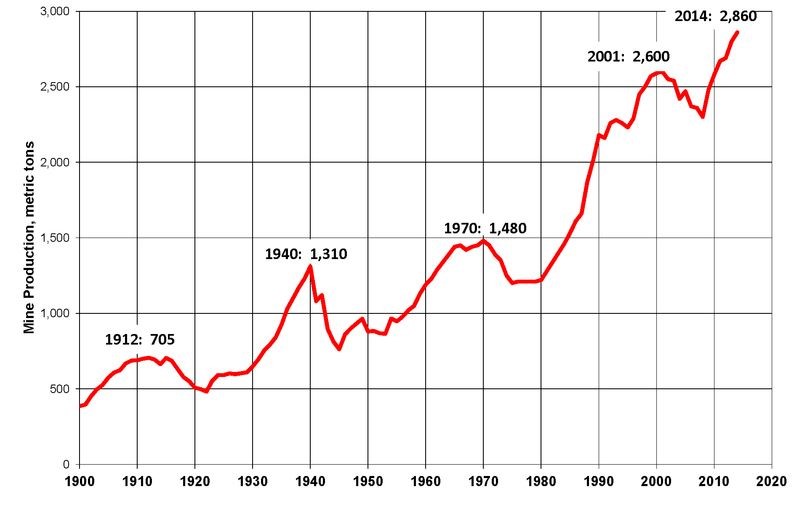

There has been no major discovery of new gold deposits since the 1890s. But there have been what appears to be a 30-year cycle of peak gold production followed by sharp declines which trigger a new depressive period. This new depressive period is marked by a ten-year period of crisis with sharp declines in prices measured in gold terms. This is shown in this graph of gold production.

The Critique of Crisis Theory blog explains: "Since 1912, there have been definite depressions in gold production approximately every 30 years. We can identify three distinct 30-year 'cycles' - if they are true cycles - from 1912 to 2001, measuring from peak to peak. The most significant and prolonged decline occurred from 1912 until the super-crisis of the early 1930s. This cycle ended with another peak in 1940, marking it as the most substantial overall increase in gold production among the three identified cycles. Between 1912 and 1940, global gold output rose by 85.58%".

"Our next 'cycle' of 1940 to 1970 saw world gold output increase by only 12.98%, far less than the preceding 30-year period. This 'cycle' of rising gold production contains no extremely severe economic crisis that would provide a powerful new stimulus to global gold production. It saw the worst war ever, World War II, which greatly increased prices in terms of not only paper money but of gold".

"Sharp rises in gold production follow severe economic crises that lower market prices from above to below the prices of production of commodities. There were no severe economic crises that sharply lowered market prices - calculated in terms of gold - between 1940 and 1970. It is not surprising that this 'cycle' of gold production showed by far the least overall increase in gold production of the three 'cycles' we are examining".

"Our final cycle - 1970 to 2001 - sees a sharper increase in gold production of 75.68%. Unlike the preceding cycle this cycle saw a tremendous decline in the golden prices of commodities - see Anwar Shaikh "Capitalism" page 64 (Golden Price Waves graph, above) - brought on by the 1970s' 'stagflation crisis'. The collapse of the market prices of commodities calculated in terms of the use value of gold bullion stimulated global gold production in a way that was not simulated between 1940 and 1970. The result was that world gold production increased by 75.68%, just a little less than the 1912-1940 period that contains the super-crisis of 1929-33 and the Great Depression".

The blog will return soon to complete its prognosis for the future of capitalism. But I assume it is not good. Gold production increased to 3,300 tonnes in 2018 and has suffered a decline to 3,000 tonnes in 2023. The peak was only 27% above the previous peak and it has declined 10% since. But stagnant or declining gold production is ultimately the cause of the recession that has hit the global capitalist economy.

Public Debt Is Exploding

We have recessions in New Zealand, Europe, UK, Australia Japan. We don't have a recession in the US yet because it is running budget deficits of over 6% of Gross Domestic Product and the US Federal Reserve was reducing interest rates at the same time to try and elect Kamala Harris to the Presidency (unsuccessfully. Ed.) as a safe pair of hands.

But public debt is exploding (now 100% of GDP) and the ruling class has voted with their feet on what this means for the US dollar. The surge in the price of gold from $US2,300 to $US2,800 in less than three months reflects a crisis of confidence that will force the US authorities to radically reduce spending and increase interest rates to levels not seen in recent years (see my previous article "The Inflation Blame Game And Marx's Crisis Theory" in Watchdog 163, August 2023) The US escaped the recession to produce what I suspect will be much more closely resembling the depression predicted by Long Wave adherents.

Watchdog - 167 December 2024

Non-Members:It takes a lot

of work to compile and write the material presented on these pages - if

you value the information, please send a donation to the address below to

help us continue the work.

Foreign Control Watchdog, P O Box 2258, Christchurch, New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Email